The $tingy Sailor

Diy trailerable sailboat restoration and improvement without throwing your budget overboard.

Flatten Your Mainsail Foot With an Outhaul

You’re familiar with basic mainsail running rigging, right? The halyard hoists it up the mast and the main sheet adjusts the angle of the sail to the hull. Both lines are important but they don’t adjust the aerodynamic shape of the mainsail, which can make a big difference if you want to get the best performance out of your mainsail.

There are three potential control lines for your mainsail to adjust its shape. Each line controls the tension on one of the three sides of the mainsail. To control luff tension, you need a Cunningham or boom downhaul like I describe in Control Mainsail Draft with a Boom Downhaul . To control leech tension, you need a boom vang like I describe in Control Your Mainsail Shape Better With a Boom Vang . In this post, I describe a trimmable outhaul to control the foot tension.

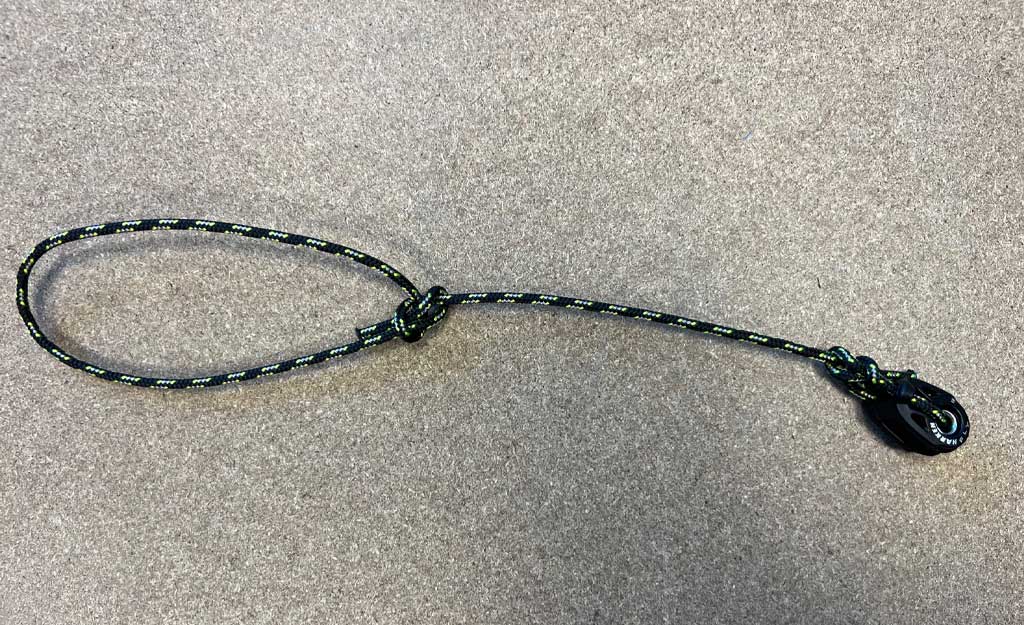

Most first generation C-22s and similar sailboats came from the factory with a simple loop of line between the mainsail clew and an eye strap at the end of the boom similar to the picture below. It holds the sail in place but that’s about all. You can’t easily trim it while sailing. If it’s loose enough to make connecting the clew easy, then it isn’t tight enough for moderate to heavy winds. If you take the time to cinch it up tight, you’ll have to untie it to take the sail off if you trailer sail. By then, the knot could be hard to loosen.

The solution is to replace that crude loop of line with a trimmable outhaul that con sists of:

- (2) Harken 085 double blocks or equivalent, one with a becket

- Fixed eye snap shackle or halyard shackle

- (2) Harken 072 3/16″ shackles or equivalent

- Ronstan small V-Cleat Fairlead or equivalent

- 5′ x 1/4″ New England Ropes Sta Set or equivalent

The pictures in this post show a five part (five line segments) outhaul only because those were the blocks that I had on hand when I rigged the outhaul. You could use fewer parts. I recommend at least two. The line is white with blue flecks in keeping with the color scheme that I describe in Choose Your Running Rigging Colors Logically . Notice in the picture below that I spliced an eye in the end of the line where it attaches to the becket. You could also use a bowline knot there but I prefer the neatness of spliced eyes, particularly here at the end of the boom where four lines are attached (main sheet not shown).

Size does matter

The challenge in this setup is to get the overall length of the outhaul as short as possible. On a C-22, there’s only about 10″ from the mainsail clew to the eye strap at the end of the boom. If the combination of blocks and other hardware is too long when you tighten the outhaul, the blocks will meet in the middle before putting enough tension on the foot of the mainsail. To solve the challenge, use the shortest shackles you can find. You might also need to shorten the becket on the one double block. Another option is to attach the working end of the line around one of the sheaves of the block itself, but that will result in less mechanical advantage.

To make the outhaul as easy to attach as possible, add a snap shackle to the working end of the outhaul for hooking to the mainsail clew. Install the fairlead cleat on the same side of the boom as where the line exits the outhaul blocks (port side in the picture below). The fairlead keeps the line captured at the boom if it gets out of hand. A foot of slack on the end makes the setup easy to trim while under sail and to loosen when removing the sail to head home.

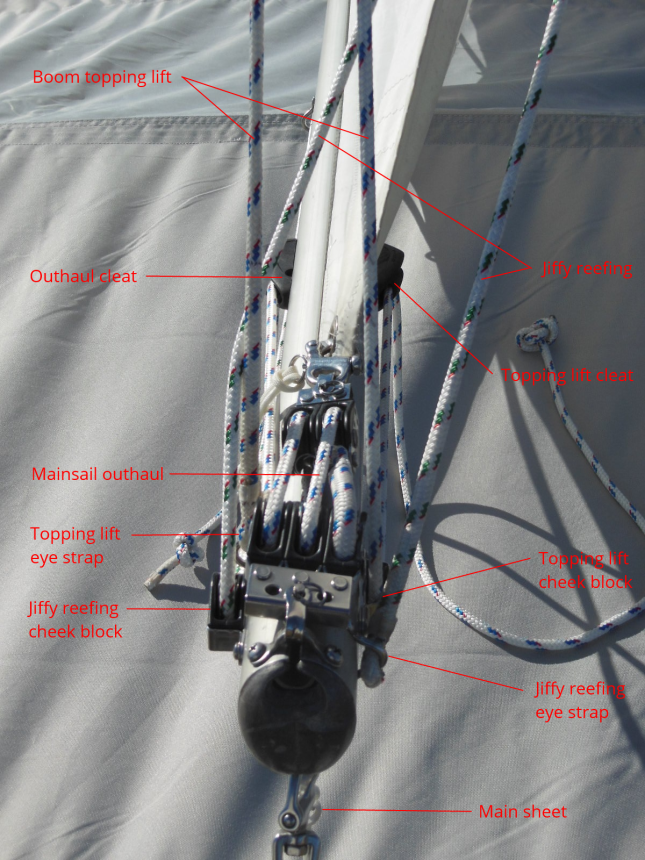

The two lines that you see hanging down from the aft end of the boom in the pictures above are the working ends of the topping lift and jiffy reefing lines that I’ve installed on Summer Dance . They’re held out of the way in the pictures for simplicity. I describe them in Let Your Boom Off Its Leash with a Topping Lift and Single Line Jiffy Reefing Made Easy , respectively. To see how all four systems (including the main sheet) fit on the boom, see the pictures below.

Keep It Simple, Skipper (KISS)

If the outhaul shown above seems too complicated or expensive for you, a simpler version is even easier to set up.

For a three part (three line segments) outhaul, you’ll need:

- Harken 083 single block with a becket or equivalent

- 4′ x 1/4″ New England Ropes Sta Set or equivalent.

Install the block on the boom eye strap, the fairlead cleat on the side of the boom, and reave the line as shown in the picture below.

In this system, the line runs through the clew grommet itself. The line isn’t as easy to trim as with multiple blocks, but it’s still easy enough.

For the complete collection of rigging projects like this one, purchase my ebook Do-It-Yourself Small Sailboat Rigging .

Would you like to be notified when I publish more posts like this? Enter your email address below to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email. You will also receive occasional newsletters with exclusive info and deals only for subscribers and the password to the Downloads page. It’s free and you can unsubscribe at any time!

Share this:

13 thoughts on “ flatten your mainsail foot with an outhaul ”.

Have been reading your posts with great interest since purchasing a ’74 in February. Planning to do the topping lift and outhaul as soon as I repair the forestay reinforcement. I’m curious about your costs. For this project, the cost of the 085 and 086 blocks alone is in the $90+ range from the two suppliers I checked. Can you recommend a less-expensive source for hardware? Thanks, Dave

Yep, they’re pricey little buggers! The main reason that I used that size of blocks was because I got the pair of them on eBay for around $25, so it was a no-brainer. If that had not been the case, I would have used something like the Harken micro blocks 227 and 228 at around half the cost. Those are also the size that Catalina Direct uses in their kit. Another benefit would be that their combined length is even a little shorter, which might make the difference with a long-footed mainsail.

When I need to buy parts at retail instead of eBay, I like defender.com. They don’t offer free shipping but their prices are among the lowest for most things and they have a great selection, which means I can usually get several things on the same order to spread the cost out and still be less than most other retailers.

Good luck with your improvement projects. Hope to see you here some more! $tingy

Thanks, $tingy. I figured you had to have done something like that. Just started the topping lift project today: bought a piece of 7/64″ Amsteel and put an Brummel eye in one end and another Brummel eye with a thimble in the other. Will have to wait till the next time I drop the mast to install it. I think the necessary hardware is already on the boom. Was thinking about attaching it to the main halyard for a quick check of the concept, either with or without the mainsail. I know the lead won’t be quite the same as attaching it alongside the backstay on the masthead truck, but it should be close.

Glad to hear you’re going for it! I think you’ll like how handy it is to just reach up and hoist the boom up whenever you need to.

Must be kinda tricky splicing line that small. I’ve only done as small as 1/4″ so far and that was tough enough. Did you make a core to core splice?

Had to look up core-to-core splice, but no, that’s not the technique I used. The Amsteel line is single-layer, not cored. I used these instructions ( http://www.l-36.com/brummel2.php and http://www.colligomarine.com/docs/misc/splicing_instructions_for_web_rev_1_2.pdf ) modified to account for the fact that the smaller line is 8-strand, not 12. {I can’t find any sites that call the 7/64th rope as 8-strand, but that’s what I have. It wasn’t hard to work with at all.

Interesting splice and it looks faster to make. I might try that on the lazy jacks I’m making. They don’t need the full strength of a conventional eye splice and I don’t want to have to make 8 of them!

The most no-nonsense, comprehensive forum I have found for our boats. Thanks. 1987 Cat. 22 SK #14218

Thanks for your comment, John. We could all gain from less nonsense and more common sense.

Hey $tingy!

My name is Nic Reid. I’m over in Bend, OR. I just bought a Tanzer 22, and I’m SOOOOOOOO excited to get going with some projects. I stumbled across your blog last night when I was looking for info on how to do projects on the cheap, and I can’t believe how awesome it is! You’ve done a stellar job, my friend. I’m working through the Mast Step post at present.

I noted that you said there is a downloadable checklist with mast step coaching and a boom crutch document as well. Call me thick, but I’m not finding those. Any help would be appreciated.

I’m excited to follow your posts. Are you still actively sailing in N. Idaho?

Congratulations on your new-to-you Tanzer! You’re in for lots of fun.

There’s a trailer sailor launch checklist and a dimensioned drawing of a mast crutch on the password protected Downloads page. The password for the page is in the confirmation email that you should have received when you subscribed. If it’s not in your Inbox, look for it in your Spam or Junk folder. If you can’t find it anywhere, use my Contact page to send me an email and I’ll send you the password.

I sail weekly on awesome Lake Pend Oreille in north Idaho. I’ve been coming here for years and still haven’t explored it all. Bend is pretty cool place too!

So, testing my understanding of pulleys used in combo like your initial project above… if I modified your second 2:1 example using a single block at the sail and a single block at the boom end, it eould just give a bit more leverage on the outhaul line, but less than the double block arrangement, right? Is it possible to pull the foot too taunt and harm the sail?

Thanks for sharing all your projects…great inspiration to make some modifications and maybe even get my V21 to sail ‘better’.

Two single blocks wouldn’t give you any more mechanical advantage, it would still be a 3-part tackle. But it would reduce friction considerably. You could try it that way and see if you like it and if it’s not strong enough, replace one of the blocks with a double block to increase the ratio.

It would take a LOT of leverage to damage the foot your mainsail with an outhaul, especially if you have rope in the foot. The only time that you would want it as tight as possible is in the highest wind conditions, which most skippers don’t want to brave anyway.

Thanks Stingy. I implemented option 2 due to space constraints on my gulf coast 18. My only change was to use a horn cleat. Love the system!

Leave a comment Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

How to Use a Sailboat's Outhaul

- Snowboarding

- Scuba Diving & Snorkeling

The Outhaul Attaches to the Sail’s Clew

The outhaul on a sailboat is one of the controls, part of the boat’s running rigging. The outhaul is a line that connects to the clew of the mainsail (the ring in the lower aft corner) and pulls the sail back toward the end of the boom. On most boats, this line or wire cable passes around a block (pulley) down into the boom, as shown in this photo.

Below shows how the other end of the outhaul is pulled to tighten the tension in the sail’s foot and explains how to use the outhaul to your advantage in different sailing conditions.

Adjust the Outhaul for Sailing Conditions

Shown here is the outhaul line exiting the boom (on the left), wrapped around a winch, and tied off on the cleat on the right. (The end of the boom is out of the picture to the left.) A winch is needed on moderate to large sailboats to exert enough tension on the foot of a large mainsail. The tighter the outhaul is pulled, the flatter the bottom of the sail becomes. The looser the outhaul, the fuller the sail.

How to Adjust the Outhaul

The principle for adjusting the outhaul is similar to that of using a boom vang in light and moderate wind.

- In light wind, the outhaul should be fairly loose, allowing the mainsail to be fuller. Wrinkles may form along the foot of the sail.

- In moderate wind, the outhaul should be moderately tight, flattening the sail and giving better shape for sailing upwind or on a reach.

- In a stronger wind, when you might need to depower the main to prevent excessive heeling, the outhaul should be very tight. A flatter sail produces less heeling force.

- How to Rig a Preventer Line

- Learn How to Sail a Small Sailboat – 1. The Parts of the Boat

- How to Gybe a Sailboat

- How to Raise the Mainsail

- How to Heave To a Sailboat

- How to Use a Mainsheet Traveler

- How to Use a Topping Lift

- Using a Sailboat Boom Vang in Sailing

- How to Use Roller Furling

- How to Tack a Sailboat

- Simple Reefing System for Sailors

- When to Adjust Sailboat Sails for Stronger Winds

- How to Anchor a Sailboat

- How to Tow a Dinghy Behind a Sailboat

- The Sunfish: A Perfect Lake or Urban Sailboat

- How to Attach Jib Sheets With a Soft Shackle

By Product Categories

Small Boat Blocks

Big Boat Blocks

Complementary Hardware

Travelers & Genoa Leads

Mainsail Handling

Headsail Handling

Mooring Solutions

Spare Parts

Accessories

Harken Canvas

Fly Soft-Attach Blocks

Carbo Air Blocks

Small Boat Classic

Flip-Flop Small Boat

GP Catamaran Ceramic Mainsheet Systems

Protexit™ Exit Blocks

Through-Deck

Wire High-Strength

Dinghy Vang

Small Boat Deck Organizers

Midrange Classic

Midrange Deck Organizers

Zircon Blocks

Element Blocks

Black Magic Air Blocks

Cruising ESP Blocks

Megayacht Blocks

Stainless Steel Blocks

Black Magic Air Runners

FlatWinder Powered Blocks

Mastbase Blocks

Over-the-Top

Crossover Blocks

Big Boat Deck Organizers

Cam Cleats & Kits

Cam Cleat Accessories

Cam Cleat Bases

Stand-Up Bases

Deck Organizers

Spinnaker Pole Cars

Soft Attachments

Fixed Padeyes

Removable Padeyes

Bolt-Down Fairleads

Grand Prix Jib Leads

Halyard Tensioners

Tiller Extensions

Peter's Desk Drawer

Dinghy Jib Leads

Crossbow Pivoting Self-Tacking Jib Traveler

13 mm Micro

22 mm Small Boat

27 mm Midrange

32 mm Big Boat

Windward Sheeting

42 mm Mini-Maxi

T-Track Genoa Lead

Access Rail System

13 mm AA Battcar System

22 mm A Battcar System

27 mm B Battcar System

32 mm C Battcar System

18 mm Switch Battcar System

26 mm Switch Battcar System

26 mm Trysail Switch

32 mm Switch Battcar System

32 mm Trysail Switch

40 mm Switch Battcar System

40 mm Trysail Switch System

Furling Mainsail Outhaul Systems

Single Line Reefing

Harken Vang-Master

Carbo Racing Foil

Small Boat Furling

Small Boat Underdeck

Reflex Furling

MKIV Jib Reefing & Furling

MKIV Underdeck Jib Reefing & Furling

Furling Accessories

Powered Furling

MKIV Ocean Furling

SnubbAir (Not a Winch)

Grand Prix Winches

Air Winches

Circuit Breakers

Analog Switches

Digital System Switch

Aluminum, Chrome & Bronze Winch Handles

Carbo OneTouch Locking Winch Handle

Service Kits

CLR Mooring Winches

Electric Captive Reel Winches

Hydraulic Captive Reel Winches

UniPower Radial

Single-Acting Integral Backstay Adjuster

Single-Acting Cylinders

Locking Cylinders

Double-Pull Cylinders

Grand Prix Cylinders

Hydraulic Cylinder Rod End Blocks

Hydraulic Cylinder End Fittings

Control Valves

Control Manifolds

Control Panels

Compact Control Panel

Rotary Pumps

Hydraulic Pump Handles

Power Systems

Repair Kits

Ball Bearings

Block Spare Parts

Traveler Cars

Furling Spare Parts

Winch Spare Parts

Winch Service Kits

Blockheads Gear

Promo & Gifts

Marine Grip

harkengear.com

Jeep/Truck tops

Garage storage

One-design Covers

Boat accessories

Canvas bags

By Type of Sailing

Dinghy / One-Design

Offshore Racing

Coastal / Day Cruising

Bluewater Cruising

Megayachts / Custom

Service Guide

Tech/Service

deck layouts

Data Sheets (SDS)

How to choose

System diagrams

Calculators

Reeving diagrams

Traveler Purchase Selection Guide

How to Choose

Testimonials

Hoister Videos

Request a Quote

Request Samples

Fabric details

Cover Styles

Canvas Videos

Contract Services

Materials and Components

Our Equipment

Contract Cut-and-Sew Project Spotlight

- Harken at the front

- Safety & Rescue

Support / Selection tools / System diagrams

Outhaul Systems

The outhaul controls and shapes the mainsail. Ease the outhaul to increase draft and power up the sail. Tighten the outhaul to flatten the sail and reduce drag and heel in heavy air.

Typical boat length: Small Boat: 22' - 28' (6.7 - 8.5 m) Midrange: 29' - 34' (8.8 - 10.4 m) Big Boat: 35' - 42' (10.7 - 12.8 m)

2:1 Internal

Suitable for dinghies or small keelboats. A flexible cable shackles to the sail and enters the boom through a wire block. Placing a block aft of the cleat allows the crew to pull from a variety of positions.

4:1 External Cascade

A simple external outhaul system. A cascade of two 2:1 tackles produces a 4:1 advantage.

5:1 Internal

This 5:1 internal outhaul is popular on small offshore boats.

6:1 Internal

A 6:1 internal outhaul system is popular on small-to medium-sized offshore boats using a traveler car to carry the clew of the mainsail.

2:1 Furling Main

Mainsails that furl into the mast are loose-footed and usually have a ball bearing outhaul car that rides the length of the boom. The outhaul starts at the car, leads through the clew block on the sail, back to the sheave on the car, and into the boom where it leads to a winch.

Product Categories

- United States

- New Zealand

- United Kingdom

- BOAT OF THE YEAR

- Newsletters

- Sailboat Reviews

- Boating Safety

- Sailing Totem

- Charter Resources

- Destinations

- Galley Recipes

- Living Aboard

- Sails and Rigging

- Maintenance

Rerigging the Boom

- By Ann Hoffner

- June 15, 2023

The mainsheet on our new Sabre 30 didn’t look right. It was the middle of a hot, airless July week. We’d bought the boat barely a month earlier, and now we were attempting to get it from New Jersey to Maine. Because of the lack of wind, the mainsail sagged as we motored up Long Island Sound. I had plenty of time to look at Ora Kali ’s boom but not a lot of incentive to solve any problems.

Then one day, we were tied to a mooring in the harbor at Scituate, Massachusetts, cheek by jowl with another Sabre 30. Wow, I realized: Our block-and-tackle arrangement is just wrong.

The weight of the boom and pressure on the mainsail on a small boat are light enough that the connection between boom and hand can be direct, but a boat of any size requires an arrangement of block-and-tackle to make it manageable.

Block-and-tackle reduces the forces necessary both to hold something in place and to lift it. In terms of mainsheet tackle, a block-and-tackle system makes it easier for the person in the cockpit to steady or control the boom and to sheet in the sail when there’s wind.

Ora Kali has three blocks in her mainsheet tackle. While the arrangement on the port side was fine for holding the boom in place, it did not take full advantage of the power for sheeting in. I took down the blocks and rearranged them. The correct arrangement gives a 3-to-1 advantage on the aft block-and-tackle, and employs the forward block mostly for turning.

The sloppy mainsheet tackle setup shouldn’t have been a surprise. This was not the first instance of the boom being rigged wrong. But Ora Kali was in such good shape for a 38-year-old boat when we bought it that I assumed something this basic would be correctly run.

When the seller bent on the sails the day before the sale, I was still dazzled by our good fortune in securing the boat and didn’t take careful notice of what he was doing. A week later, we took down the mainsail before we sailed off to inspect it for wear that might need repair and noticed that the tack cringle was hooked onto one of a pair of hooks normally used when reefing the sail. It became obvious why this was done: The gooseneck fitting was set up backward, putting the attachment point for a tack shackle behind the hooks. Useless. In fact, it turned out there was no tack shackle. It was a simple matter to reposition the reef hook/tack assembly, and I eventually found a tack shackle that fit.

Another puzzle we chose to work around in the interest of setting off for Maine was a barely functioning outhaul. An outhaul is used to tension the foot of the mainsail and attaches to the clew or clew car, then runs to the after end of the boom and around either an internal or external sheave and forward, where it can be adjusted. If the sail is fixed to the boom with slides or bolt rope, as it was on Oddly Enough , our Peterson 44, then an outhaul isn’t crucial for setting the general sail shape. In fact, we rarely touched ours.

With a loose-footed main, the outhaul has more work to do. The Sabre 30 is the first boat I’ve owned with a loose-footed main, and I didn’t understand what the rig was. The rope that attached to the clew car was not the same rope as emerged from an exit plate forward on the boom. When we tried pulling on either end, the car would budge only so far, and we never were able to fully stretch out the loose foot. I assumed that the outhaul had broken and a knot someone had made to add new rope to the original was jamming inside.

During the spring refit, I looked up in-boom outhaul rigs and saw that they usually include a block-and-tackle to add purchase for adjusting the mainsail foot. This is fixed midway by a bolt through the boom. I took Ora Kali ’s boom end off and discovered that the bolt holding the block had been run right through it rather than through a shackle, keeping it from swiveling. The two pieces of line were too big to run alongside each other freely. Between a seized block and the friction built up in the lines, the outhaul was useless.

The tricky part of this rerigging was snagging the shackle. I used a messenger line to pull the block-and-tackle into approximate position inside the boom, then ran a screwdriver through holes in the boom and the shackle.

The last piece of boom rigging that bothered me was the topping lift. On Ora Kali , this was a fixed length of 7-by-19 wire rope attached at the masthead with a small block at the other end. A Dacron rope ran from a shackle on the end of the boom, up over this block, down to the boom end sheaves, then inside to an exit sheave.

This is a fairly common way of rigging a topping lift, but I’m not a big fan of using wire in running rigging.

The primary purpose of the topping lift is to take the weight off the boom when the sails are furled and for reefing. On my previous cruising boats, I had topping lifts that doubled as a spare main halyard.

To fulfill both of these needs, I replaced the system with a single rope outhaul, shackling one end of the new topping lift to the after end of the boom, leading the other end over an unused masthead sheave, and installing a halyard exit plate at the bottom of the mast for the topping lift to run out and be adjusted. The lift is simpler, which I like, but running it over a masthead sheave puts it more in the way of the mainsail leach. To make sure we ease it when the sail is raised, I plan to bring the bitter end of the topping lift back to the cockpit to an existing set of sheet stoppers and a winch on the coachroof beside the main halyard and the mainsheet.

All in all, I now have a cleaner, more rationally rigged boom.

Ann Hoffner started sailing when she was 9 years old. Along with her husband, Tom Bailey, she spent 10 years cruising on their P-44, Oddly Enough , in the South Pacific, Australia and Borneo. Ora Kali , a nimble, shoal-draft Sabre 30, is now teaching them the joys of Maine coastal cruising.

- More: Hands-On Sailor , How To , Print May 2023 , rigging , sails and rigging

- More How To

How To Prioritize Your Sailboat’s Spring Checklist

How to protect your spars from corrosion, sailing totem refit series: the forward head makeover, fatty goodlander: dealing with chafe while cruising, tradewinds debuts 59-foot twe6 smart electric yacht, good bread for good health, center of effort, the halfway point: sailing to bermuda.

- Digital Edition

- Customer Service

- Privacy Policy

- Email Newsletters

- Cruising World

- Sailing World

- Salt Water Sportsman

- Sport Fishing

- Wakeboarding

Yachting Monthly

- Digital edition

Mainsail furling systems: an expert guide

- Graham Snook

- December 21, 2020

Some sailors swear by mainsail furling systems, others swear at them. Graham Snook looks at way to keep your furling mainsail in check

In-mast furling mainsails (left) have evolved significantly, and vertical battens allow more roach and better sail shape. Credit: Graham Snook

Mainsail furling systems have come on a long way.

Sails no longer need to be wrapped around a boom, nor does an in-mast mainsail need to be the hollow-leached, baggy triangle we first saw decades ago.

Furling mainsail systems can now offer more sail area than a traditional slab-reefed mainsail.

Be that as it may, every slab-reefed sailor knows a horror story about in-mast or in-boom furling that is enough to make them steer well clear, while those that have furling mains wouldn’t put to sea without one.

There is little doubt that furling mainsails are gaining in popularity, even for serious offshore cruising boats.

Get mainsail furling wrong and it can lead to costly and potentially dangerous problems. Credit: Graham Snook

In 2018, 38% of boats sailing round the world in the World ARC had furling mainsail.

Hallberg Rassy reports that almost all new owners buying boats over 40ft opt for furling mainsail systems, with Discovery reporting a similar trend.

So has the reputation of furling mainsails been unfairly tainted, and are they more prone to user error, or have the systems ironed out the glitches?

Whether you’ve got a furling main on your own boat, or if you’ll be using one when you charter, it’s worth knowing how to avoid the pitfalls of furling mainsails.

How do furling mainsail systems work?

In an age where we expect everything just to be simple and to work, letting off one line, and pulling another to make the mainsail appear or disappear sounds appealing, but what is the best way to furl the mainsail?

Is there a correct way to do it?

‘Carefully,’ replies Jeremy White,of Elvstrøm Sails UK. ‘They’re mechanical systems and they need to be operated correctly.’

Whether you have in-boom or in-mast, they both work on a similar principle which anyone with a furling genoa will be familiar with.

Inside the mast is an aluminium foil that takes the luff of the mainsail, and in a boom a mandrel takes the foot of the mainsail; both the foil and the mandrel revolve to roll up the sail.

A lot of issues with in-mast furling are caused by the sail not furling properly inside the mast and the furl being too bulky or the sail rubbing on the inside of the mast.

Many in-boom problems are caused by an uneven furl with the sail bunching at one end or the other.

There are a number of issues to look out for with each system to ensure stress-free furling.

Different options

If you’ve bought a new boat that was ‘good value’ and it came with sails, question how good those sails really are.

Many original Dacron sails are built to a price that will get you on the water and get you sailing, but they may not be built for longevity or performance unless you’ve specified them and know what you’re getting.

There has been much advancement in furling mainsail design, improved materials, vertical battens, and increased sail area.

Many new furling mainsail systems present a larger sail area than that of a conventional slab reefing sail.

But what should you be looking for when buying a new sail?

‘Whichever sailmaker you choose, get the highest quality material you can afford,’ advises Jeremy.

It’s a false economy to buy cheaper sailcloth as it will stretch and you’ll be left with a baggy sail after a few seasons.

For example, the luff of laminate sail (on a 45ft yacht) might only stretch 15mm over its lifetime, but on a polyester sail that might be as much as 15 cm.

That excess sail has to roll up in the same space as did when it was new.

For those wanting maximum sail area, and sail support, full-length vertical battens are the way forward.

These support the leech giving a good full roach, and importantly, they support the sail over its full height which gives it rigidity while it’s being furled, whereas shorter, vertical roach battens can leave the sail unsupported at their base causing furling problems.

For those without the budget or desire for a battened sail using modern materials, a sail with a hollow leech still offers many advantages over a slab reefing system, namely ease of reefing, the ability to set exactly the right amount of sail, and the simplicity of stowing, even if you do lose some power from a smaller sail area and a less perfect aerofoil sail shape.

If you’re having new sails made consider getting them silicone-coated.

This helps the sail slide over itself making the furl inside the mast tighter.

In-mast furling

It may be a simple system, but how you unfurl and furl the main will help avoid problems.

If you were to look down from the top of the mast, the foil usually rolls onto the foil in anti-clockwise direction, that is, the unfurled sail comes off the starboard side of the foil, though it’s worth checking on yours.

This is the key to getting in-mast furling to work correctly; trying to furl on a port tack drags the full height of the sail over the side of the mast slot, adding friction where there shouldn’t be any.

Furling on starboard tack obviates most of this friction while you furl.

Full-height battens support a larger roach, but make the furled sail more bulky. Credit: Graham Snook

Whether letting the sail in or out, the first thing is to release the backstay (to straighten the mast so the foil doesn’t rub) and put the boat on a starboard tack – with the wind slightly forward of the beam – this is so the sail feeds cleanly into the mast and around the furler inside.

Unfurling the sail is usually pain-free if the sail was furled correctly.

With the yacht on a starboard tack and the wind forward of the beam, release the mainsheet and vang.

Ensure the furling line is released then pull out the sail using the outhaul.

Ease the outhaul as your furl so the sail doesn’t flog but isn’t loaded up either. Credit: Theo Stocker

You shouldn’t need to control the furling line as there should be no pressure on the sail, even on a windy day.

If you intend to be reefed, however, don’t let it run unchecked. When the right amount of sail is out, make off the furling line. If you’re reefed, tension the outhaul to give the sail the correct shape (flatter in stronger winds and when close-hauled) then set the mainsheet and vang and away you sail.

- Release the backstay (if you have one)

- Put the boat on a starboard tack – with the wind slightly forward of the beam

- Release the mainsheet and vang

- When the right amount of sail is out, make off the furling line

- Tension the outhaul to give the sail a correct shape, then sheet in

To furl the sail, after letting off the backstay and putting her on a starboard tack with the wind slightly forward of the beam, let off the mainsheet and then ease the outhaul a little and start to furl.

Always look at the sail as you’re furling – you’ll be able to notice issues as they happen and not after you’ve wound an inch-thick clump of sail through a half-inch gap.

Having different coloured lines can make things simpler for your crew. Credit: Theo Stocker

If your sail has full-length vertical battens ensure the first batten is parallel with the mast when it enters, and if reefing, leave a batten just outside the mast groove.

Keeping too much tension on the outhaul will drag the foil aft in the mast, bending it and causing the sail to rub against the inside of the mast, creating friction.

Once you’ve taken the slack out of the sail, ease the outhaul and take in on the furling line again.

Try not to let the sail flog as this also bends the foil and causes more friction.

Repeat the ease-furl process until only the UV protection strip is showing.

Sail on starboard with wind forward of the beam for easy furling. Credit: Theo Stocker

If you have laminate sails, and they have been furled away wet, try to dry them at the first opportunity.

If you’re having problems furling using the lines, don’t be afraid to go to the mast with a winch handle and furl the sail at the mast.

Try it one day, it is remarkably easy.

If you’re having to do anything different, such as raising the boom or chanting a prayer to the god of furling fails, it’s worth looking at your system in detail for problems.

- Release the backstay

- Ease the outhaul a little

- Take in on the furling line

- Keep easing the outhaul and taking in on the furling line

- Furl the sail until the UV strip is showing at the mast

Problem solving

If furling the right way still isn’t working for you, there are a number of things to consider…, 1. understand your system.

First to check is to have a look inside your mast at which way your system should furl.

If your furling system has the option, put a winch handle in the furling mechanism at the mast and turn it the direction indicated to make sure the sail is going into the mast in the correct direction.

Clicking over the ratchet at the mast before it’s time to furl will ensure it always rolls in the right direction.

2. Assess your sails

The biggest cause of problems is the sail itself – how old it is and the material it is made from.

Stretch in the cloth makes baggy sails, which furling systems will happily munch on.

Furling mainsails are cut flatter than conventional slab-reefing sails as accommodating the belly of the sail is problematic.

An old or baggy sail may cause jams, as will creases from not enough halyard tension. Credit: Theo Stocker

Some older furling mains may have be made with an inappropriate, fully-bellied shape.

If your polyester sails have a deep belly, think about getting new ones as you’ll be fighting a losing battle.

As the belly folds, it doubles the thickness of the furl, causing unsightly and inefficient creases at best, and hideous sail jams or rips at worst.

3. Adjust halyard tension

Excess halyard tension can also cause the fabric to bunch up; vertical creases at the luff cause the sail to fold over itself.

Vertical creases at the luff reveal too much halyard tension, and potential for more snags. Credit: Theo Stocker

To resolve this, release the halyard until you have horizontal creases at the luff, then add just enough tension to remove them, though you may need to adjust this when underway.

4. Check the backstay

While the mast is bending, the foil inside it remains straight; the furled sail will bind at the apex of the mast’s bend.

If all of this fails, it’s worth calling a rigger to check the foil tension.

If this has gone slack, as you furl the foil will bend and rub against the mast.

5. Smooth it out

The next thing to look at is reducing friction.

As is often the case, the lines to your furling gear and outhaul are led through various fairleads and blocks across the deck and up the mast.

Move deck organisers to give slacker turning angles. Credit: Theo Stocker

Make sure all the angles they have to go through are a wide as possible – consider moving them if not – and all blocks and sheaves are running smoothly.

A good wash with fresh water and a squirt of dry lubricant can work wonders.

In-boom furling

Not a new concept, in-boom furling is an elegant solution, but brings its own challenges.

Unlike in-mast furling, in-boom systems can be retrofitted in place of conventional slab reefing.

For an in-boom furling system to work efficiently, however, it has to overcome a number of problems.

To start with, have a crew on deck to watch the sail as it furls to spot any issues. Credit: Advanced Rigging and Hydraulics

First of all, the sail has to be led from the boom to the mast, but there needs to be space for the bearings for the central mandrel and the boom’s gooseneck fitting, so the whole sail has to move aft along the boom.

To combat this, many in-boom systems have a protruding track on the trailing edge of the mast, while other units have the reefing mechanism at the aft end of the boom, or sometimes you’ll find a combination of both.

Whatever the system, there is usually a flexible feeder to guide the sail from the boom and feed it into the mast track.

The furling drum at the outboard end of the boom brings the main closer to the mast. Credit: Advanced Rigging and Hydraulics

Another issue with in-boom furling is the bolt rope, as Andy Cross from Crusader sails explains.

‘The sail has to use a bolt rope, and with it comes friction. Unlike a furling genoa that may only be raised and lowered once a season, the mainsail is nearly always used so the luff tape has to be reinforced.’

Any wear or damage to the bolt rope also requires a new bolt rope along the full luff of the sail, as any repairs would soon wear through and increase the friction.

The necessary extra reinforcement at the luff brings with it another problem: extra cloth thickness at the front end of the sail.

When reefing, stop when a batten is just above the mandrel, then take in on the furling line. Credit: Graham Snook/Yachting Monthly

As the sail rolls around the mandrel there is more sail material at the luff than across the rest of the sail.

The solution?

To slightly raise the aft end of the boom, allowing the extra sailcloth at the luff to roll at a rate that matches the leech.

The angle from the mast to the top of the boom has to be 87° to the mast, 3° above perpendicular.

The full-length battens in the mainsail help stabilise the sail as it furls and the batten pockets have been attached to the sail to match the mandrel angle.

It’s the thickness of cloth at the luff and the battens that make the correct boom angle the most important part of the system.

The necessary bulk of the boltrope makes the boom angle critical.

Get that right and your life suddenly becomes a whole lot easier.

It’s essential to mark the vang when the boom angle is correct.

Some owners choose to make a strop, running next to the vang, out of a low-stretch material like Dyneema, so the topping lift can be pulled taught and the strop prevents the boom raising higher than it should.

When marking or limiting the boom angle, it must be easy for any crew to see, by day or night.

How to get it right

1. prepare to set sail.

‘Before raising, lowering, or reefing the mainsail,’ explains Kim Petersen, Elvstrøm Denmark’s in-boom sail specialist, ‘get into the habit of always releasing the backstay tension – this will successfully straighten the mast and takes any flattening tension out of the sail – and then making sure the boom is at the correct angle – this is extremely important.’

Be careful with electric winches not to over-tighten halyards. Credit: Graham Snook

To raise the sail, after slackening the back stay and adjusting the boom level, point the boat into the wind, release the mainsheet and take up on the mainsail halyard, making sure that the furling line can run free as you hoist the mainsail.

Once set, increase the halyard tension until the horizontal creases at the luff have just gone.

2. Reducing sail power

If you don’t need full sail, only raise the sail until the nearest batten is at the mandrel.

Rather than being able to reef at any point, where the lower battens are fitted, the sailmaker will have reinforced the sail to take the clew loads.

Not reefing at these points means an area of unreinforced leech could be required to take a load it was not designed for.

Each batten represents a reefing point. Credit: Graham Snook

You’ll end up with fullness at the foot of the sail and a stretched leech, or a damaged sail.

If you need to flatten the sail, for better pointing or in stronger winds, take in on the furling line without adjusting the halyard tension.

This will give the same result as using a cunningham to tighten the luff.

Furling the main

When lowering the sail, release the backstay and set the boom at the correct angle.

It’s then best to take all the pressure off the sail by heading into the wind.

It doesn’t matter if the sail is flogging; the battens keep the sail rigid and support it as it furls.

If there is any pressure on the sail, this will cause it to furl unevenly.

With in-boom reefing you should still have a good sail shape even when deeply reefed. Credit: Graham Snook/Yachting Monthly

Unlike an in-mast furling system, where the sail is visible, on an in-boom system everything is happening on top of the boom, overhead and out of sight.

If you have a crew member spare and it’s safe, sending them to the mast to keep an eye on the sail as it furls can prevent damage, at least for the first few times using the system.

Pull in on the furling line, slowly and smoothly releasing the mainsail halyard, but keep a bit of tension on it.

Continues below…

The tools and spares you shouldn’t sail without

Give a thought to your inventory this winter to keep you cruising next season, says Rachael Sprot

Why you should regularly check your deck fittings

What’s really going on under your deck fittings? Ben Sutcliffe-Davies investigates the hidden weaknesses

Essential reefing tips for cruisers

Reefing: how, when and why do we do it? The answers may not be as straightforward as you think, says…

How to: replace a halyard

Whether you’re replacing an old halyard for new, or mousing the mast over winter, Rubicon 3’s Rachael Sprot explains how…

If you have too much tension the sail will want to roll away from the mast; if you’re seeing creases running from the bottom of the track to the boom at 45°, release the halyard a little more.

If the sail is rolling up toward the mast, you’ll need to increase the tension a little.

As the sail furls, the luff tape will naturally first roll aft, then move forward and repeat this – it’s all perfectly normal.

Once the sail is fully down, tuck the head into the boom if your system allows it, and add the sail cover.

Reefing underway

To reef when sailing, release the backstay and set the boom angle.

In rough weather, or when there are big seas, it’s best to take up on the boom’s topping lift to secure the boom and stop it rising and falling as the yacht goes over the wave crest.

Cover the sail once stowed to protect from UV. Credit: Advanced Rigging and Hydraulics

You’ll find it easier if you can bring the boat onto the wind and release the mainsheet to remove all drive from the mainsail; if the sail is flogging it’s depowered and can still be furled.

Next, take in on the furling line while slowly and smoothly easing the halyard as the sail furls.

Graham Snook is a marine photographer and journalist who has been involved in testing yachts and equipment for over 20 years. Credit: Graham Snook

Once you’ve reached a point where the batten is at the mandrel on top of the boom, make off the halyard and then furl the sail until the batten is under the mandrel.

Without reefing pennants to hold and support the clew of the sail, the loads are transferred to the batten and the cloth around it.

Because of this, it’s recommended that for in-boom reefing mainsails, a stronger stretch-resistant cloth like Dacron reinforced with Vectran or Dyneema or a tough cruising laminate cloth be used.

Whichever mainsail furling system you have or choose, spending a bit of time practising what works and what doesn’t on your system, at a time when it’s convenient to you, will pay dividends when you find you do need to reef.

Mainsail furling has had a bad reputation in the past, but used properly and with a little care, there’s no reason why it shouldn’t give you trouble-free sailing for years to come.

To raise the sail

- Release the backstay tension

- Make sure the boom is at the correct angle – use a strop or mark the vang if necessary

- Head up into the wind – it doesn’t matter if the main flogs as it goes up

- Release the mainsheet

- Take up on the mainsail halyard, but do not overtighten

To lower the sail

- Make sure the boom is at the correct angle

- Point the yacht into the wind

- Take in on the furling line as you ease the halyard at a steady rate

⛵️ Fast Dispatch - Getting You Back on the Water ⛵️

- Gelcoat Fillers

- Dry Lubricants

- Adhesive Glues

- Hooks & Clips

- Catamaran Launching Trollies

- Jockey Wheels

- Hitch Locks

- Lighting Board

- Breakaway Cables

- Clew Straps

- Upper Masts

- Lower Masts

- Rope Thimbles

- Wind Indicators & Burgees

- Parrel Beads

- Whipping Twine

- Sailmakers Palm

- Digital Compasses

- Laser Products

- Numbers & Letters

- Dinghy Covers

- Under Covers

- Catamaran Covers

- Single Handed

- Double Handed

- 18 Foot Skiff

- Exocet Moth

- Musto Skiff

- Dart 15/ Sprint 15

- Hurricane 5.9

- Laser Bahia

- Laser Cascais

- Laser Funboat

- Laser Stratos

Your Cart is Empty

- £0.00 Subtotal

Tax included and shipping calculated at checkout

Order before midday Monday to Friday and we will ship your order the same day.

- 01268 222912

- Accessories

- Sails & Covers

- Rope Lengths

- Parts By Boat

- Boat Care & Cleaning

- Splicing Tools

- Boat Covers

- Dinghy Rope Lengths

- Laser Rope Lengths

- RS Rope Lenghts

- Catamaran Rope Lengths

- Laser Performance

- Topper Sailboats

- Other Boats

- Mens Sailing Clothing

- Womens Sailing Clothing

- Repair Kits

- Skiff Suits

- Life Jackets

- Trapeze Harnesses

- Buoyancy Aids

- Hiking Pads & Pants

- Hiking / Toe Straps

Zhik Superwarm

- 100m Rope Reel

- Polyester Ropes

- Control Lines

- Double Braids

- Braid On Braid

- Anchor Lines & Ropes

- Spools & Reels

- Windsurfing

Mini Spools

- Single Block

- Double Block

- Triple Block

- Soft Attach

- Split Rings & Pins

- Inspection Hatches & Covers

- Bungs & Sockets

- Rudder & Tiller Parts

- Bushes & Fairleads

- Marine Screws

- Penny Washers

- VHF Aerials & Antennas

- Marine Tapes

- Traveller Systems And Parts

- Traveller Blocks

- Pico Hull & Deck Fittings

- Hull & Deck Fittings

- Laser Boats

- Laser Sails

- Laser Sail Packages

- Laser Spars

- Laser Rig Packages

- Laser Foils

- Laser Hull & Deck Fittings

- Laser Ropes

- Laser Dinghy Covers

- Devoti ILCA Boats

- ILCA Sail Packages

- ILCA Rig Package

- Devoti KDK Boats

New Devoti ILCA

Search our chandlery

🚚 Fast Dispatch and a 5 Star Rated Service You Can Count On ✅

How to Build a Laser XD 6-1 Outhaul System

November 11, 2022 3 min read

How to Build a Laser 6-1 Outhaul System

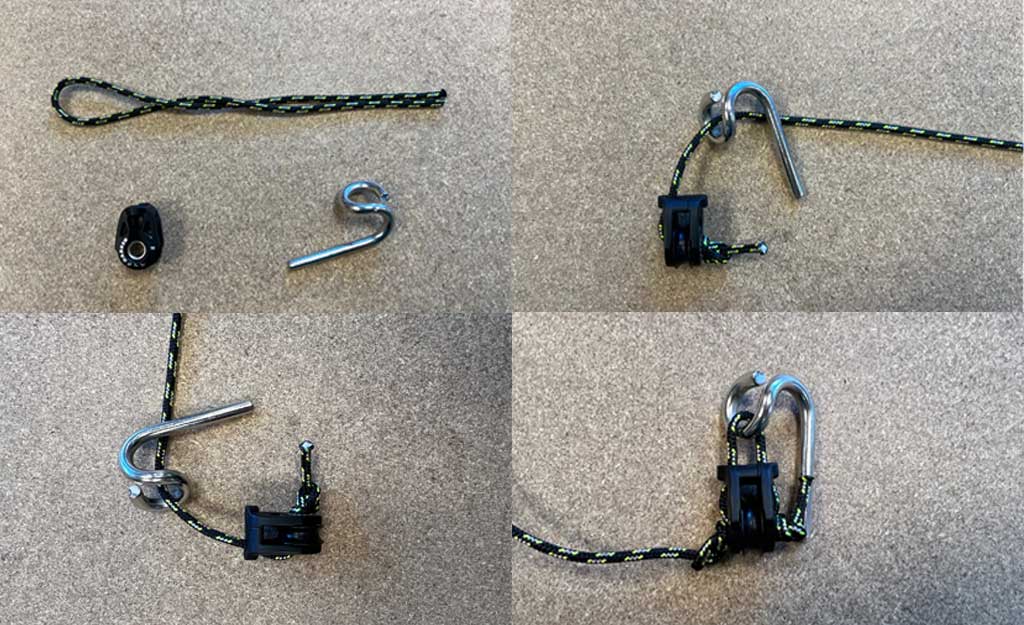

The Laser 6-1 Outhaul System is now the standard that comes with all new boats. If you are finding your outhaul is very difficult to adjust it may be time to upgrade your system.

In this article, we walk you through what you'll need and how to make a Laser 6-1 Outhaul System step by step.

Items You Will Need

You can also buy the full Laser Outhaul Kit on our website.

Some ropes will need to be cut to your correct length once the system is made. This system is tied together with knots however, we would always recommend when working with Dyneema lines to splice them as this is stronger than knots.

- x4 Harken 2698

- x1 Laser Clew Hook

- 2m of 3mm Rig 12 Dyneema

- 3m of 3mm Kingfisher Evo Race Rope

- 6m (or 7m for 4.7 Rigs) of 4mm Kingfisher Evo Race Rope (Secondary Control Line

The first part of the Outhaul System is going to be the clew block and hook. There are lots of different ways that people rig this. We will do it per the instructions you receive with a new boat. Take one of the 18mm blocks, the clew hook and one length of the 3mm race rope.

Tie a stopper knot in one end of the line and thread it through the centre of the block and up through the top of the block. Now grab your clew hook and thread the line through and back down into the top of the block. Lastly back through the middle of the block and tie another figure of 8.

Primary Dyneema

Take your length of 3mm Dyneema and tie a bowline around the eye on the boom end.

Now thread your line through the clew block from step one and the Dyneema back through the boom eye. The rope will then run along the boom towards the front of the boat.

Control line

Take your 4mm Race rope and an 18mm block. Thread the 4mm line about 3 inches through the centre of the block.

Now with the Primary Dyneema thread it into the top of the same 18mm and tape both lines together using the photo below as a reference.

Pull both through and tie a bowline in each.

Take your next 18mm block and a length of 3mm race rope and tie it into the cleat on the boom. This should face backwards down the boom towards the back of the boat.

Control line

Now thread the control line from the bowline you have tied through the mid-block tied to the boom and back through the block the bowline is tied onto going around the sheave. This will create your 6 to 1 purchase.

Take your last 18mm block and 3mm race top and tie a bowline around the block and the loose end will be tied around the lower mast where the boom and mast meet. This block acts as the turning point where the control line rope goes along the boom and down towards the deck plate.

The control line rope will then go through the deck block at the bottom of the mast and backwards through the cleats on the deck.

Elastic/ Shockcord

Thread the shockcord through the cleat on the top of the boom then tie a stopper knot. Now the other end can be tied to the sail or the clew hook as shown below.

If you have any questions on the Laser 6 to 1 outhaul system please get in touch with our team who are always happy to help.

Recent Articles

- 90˚ Marked Laser/ILCA Main Sheet - Sailing Chandlery

- Pre season Check List

- Where Should My ILCA Tell Tales Go

- What Are The Basic Tools Needed To Start Rope Splicing?

- You Don't Always Need Dyneema

- Boat Care and Cleaning Products

- Ropes for Club Boats and Club Dinghies - The Bosuns Guide

- Why You Should Use Two Sailing Watches

- Setting Your ILCA Dinghy Controls Up For Success

- 7 Items To Make Your Boat Go Faster in 2023

Let customers speak for us

WIP have really pulled out all the stops on this impact vest to suit all forms of hi-performance watersports. Feels great on, good snug fit - no restrictions to movement and doesn't impact on trapezing like a lot of buoyancy aids. A very well made, high quality vest that has everything you need to keep you safe on the water.

Purchased for my old Albacore sailing dinghy. This is a well made quality cover with straps and clips that look like they’ll last many years. I no longer have to bail out the boat before sailing!

Found the staff at Sailing Chandlery most helpful to a no-yachtsman with flags to fly to cheer the day.

It may seem strange but my husband purchased this item as he was making me some wooden bunting for our outside space. The range of colours was fab and the rope is ideal for our needs. Easy to order and arrived quickly….great service

Made with good quality material and sizing is accurate. Comfortable to wear with plenty of secure pocket space. Buoyancy aid arrived promptly and securely wrapped.

Waterproof, spacious and different ways to carry it

Perfect arrived on time....

nothing to fault it, it’s got ce rating and worked great on a trip down to weymouth

Order placed and boom received in time to get back on the water, class legal, packed accurately in a bulletproof bag with bubble wrap and extra foam to protect blocks and fittings. Any defect? Nope! Thanks all Sailing Chandlery’s staff

Good sized, well made waterproof bag, ideal for sailing

Easy to fit and great feel.

Good quality with novel scull and crossbones adhesive tabs.

I ordered a rope bag for learning knots this item arrived quickly and is much appreciated

Top Notch Service !👍

Great addition to our training fleet - good product backed up by brilliant delivery. Thanks.

SIGN UP TO OUR NEWSLETTER

Save up to 40% on your next order.

Beginner’s Guide: How To Rig A Sailboat – Step By Step Tutorial

Alex Morgan

Rigging a sailboat is a crucial process that ensures the proper setup and functioning of a sailboat’s various components. Understanding the process and components involved in rigging is essential for any sailor or boat enthusiast. In this article, we will provide a comprehensive guide on how to rig a sailboat.

Introduction to Rigging a Sailboat

Rigging a sailboat refers to the process of setting up the components that enable the sailboat to navigate through the water using wind power. This includes assembling and positioning various parts such as the mast, boom, standing rigging, running rigging, and sails.

Understanding the Components of a Sailboat Rigging

Before diving into the rigging process, it is important to have a good understanding of the key components involved. These components include:

The mast is the tall vertical spar that provides vertical support to the sails and holds them in place.

The boom is the horizontal spar that runs along the bottom edge of the sail and helps control the shape and position of the sail.

- Standing Rigging:

Standing rigging consists of the wires and cables that support and stabilize the mast, keeping it upright.

- Running Rigging:

Running rigging refers to the lines and ropes used to control the sails, such as halyards, sheets, and control lines.

Preparing to Rig a Sailboat

Before rigging a sailboat, there are a few important steps to take. These include:

- Checking the Weather Conditions:

It is crucial to assess the weather conditions before rigging a sailboat. Unfavorable weather, such as high winds or storms, can make rigging unsafe.

- Gathering the Necessary Tools and Equipment:

Make sure to have all the necessary tools and equipment readily available before starting the rigging process. This may include wrenches, hammers, tape, and other common tools.

- Inspecting the Rigging Components:

In the upcoming sections of this article, we will provide a step-by-step guide on how to rig a sailboat, as well as important safety considerations and tips to keep in mind. By following these guidelines, you will be able to rig your sailboat correctly and safely, allowing for a smooth and enjoyable sailing experience.

Key takeaway:

- Rigging a sailboat maximizes efficiency: Proper rigging allows for optimized sailing performance, ensuring the boat moves smoothly through the water.

- Understanding sailboat rigging components: Familiarity with the various parts of a sailboat rigging, such as the mast, boom, and standing and running riggings, is essential for effective rigging setup.

- Importance of safety in sailboat rigging: Ensuring safety is crucial during the rigging process, including wearing a personal flotation device, securing loose ends and lines, and being mindful of overhead power lines.

Get ready to set sail and dive into the fascinating world of sailboat rigging! We’ll embark on a journey to understand the various components that make up a sailboat’s rigging. From the majestic mast to the nimble boom , and the intricate standing rigging to the dynamic running rigging , we’ll explore the crucial elements that ensure smooth sailing. Not forgetting the magnificent sail, which catches the wind and propels us forward. So grab your sea legs and let’s uncover the secrets of sailboat rigging together.

Understanding the mast is crucial when rigging a sailboat. Here are the key components and steps to consider:

1. The mast supports the sails and rigging of the sailboat. It is made of aluminum or carbon fiber .

2. Before stepping the mast , ensure that the area is clear and the boat is stable. Have all necessary tools and equipment ready.

3. Inspect the mast for damage or wear. Check for corrosion , loose fittings , and cracks . Address any issues before proceeding.

4. To step the mast , carefully lift it into an upright position and insert the base into the mast step on the deck of the sailboat.

5. Secure the mast using the appropriate rigging and fasteners . Attach the standing rigging , such as shrouds and stays , to the mast and the boat’s hull .

Fact: The mast of a sailboat is designed to withstand wind resistance and the tension of the rigging for stability and safe sailing.

The boom is an essential part of sailboat rigging. It is a horizontal spar that stretches from the mast to the aft of the boat. Constructed with durable yet lightweight materials like aluminum or carbon fiber, the boom provides crucial support and has control over the shape and position of the sail. It is connected to the mast through a boom gooseneck , allowing it to pivot. One end of the boom is attached to the mainsail, while the other end is equipped with a boom vang or kicker, which manages the tension and angle of the boom. When the sail is raised, the boom is also lifted and positioned horizontally by using the topping lift or lazy jacks.

An incident serves as a warning that emphasizes the significance of properly securing the boom. In strong winds, an improperly fastened boom swung across the deck, resulting in damage to the boat and creating a safety hazard. This incident highlights the importance of correctly installing and securely fastening all rigging components, including the boom, to prevent accidents and damage.

3. Standing Rigging

When rigging a sailboat, the standing rigging plays a vital role in providing stability and support to the mast . It consists of several key components, including the mast itself, along with the shrouds , forestay , backstay , and intermediate shrouds .

The mast, a vertical pole , acts as the primary support structure for the sails and the standing rigging. Connected to the top of the mast are the shrouds , which are cables or wires that extend to the sides of the boat, providing essential lateral support .

The forestay is another vital piece of the standing rigging. It is a cable or wire that runs from the top of the mast to the bow of the boat, ensuring forward support . Similarly, the backstay , also a cable or wire, runs from the mast’s top to the stern of the boat, providing important backward support .

To further enhance the rig’s stability , intermediate shrouds are installed. These additional cables or wires are positioned between the main shrouds, as well as the forestay or backstay. They offer extra support , strengthening the standing rigging system.

Regular inspections of the standing rigging are essential to detect any signs of wear, such as fraying or corrosion . It is crucial to ensure that all connections within the rig are tight and secure, to uphold its integrity. Should any issues be identified, immediate attention must be given to prevent accidents or damage to the boat. Prioritizing safety is of utmost importance when rigging a sailboat, thereby necessitating proper maintenance of the standing rigging. This ensures a safe and enjoyable sailing experience.

Note: <p> tags have been kept intact.

4. Running Rigging

Running Rigging

When rigging a sailboat, the running rigging is essential for controlling the sails and adjusting their position. It is important to consider several aspects when dealing with the running rigging.

1. Choose the right rope: The running rigging typically consists of ropes with varying properties such as strength, stretch, and durability. Weather conditions and sailboat size should be considered when selecting the appropriate rope.

2. Inspect and maintain the running rigging: Regularly check for signs of wear, fraying, or damage. To ensure safety and efficiency, replace worn-out ropes.

3. Learn essential knot tying techniques: Having knowledge of knots like the bowline, cleat hitch, and reef knot is crucial for securing the running rigging and adjusting sails.

4. Understand different controls: The running rigging includes controls such as halyards, sheets, and control lines. Familiarize yourself with their functions and proper usage to effectively control sail position and tension.

5. Practice proper sail trimming: Adjusting the tension of the running rigging significantly affects sailboat performance. Mastering sail trimming techniques will help optimize sail shape and maximize speed.

By considering these factors and mastering running rigging techniques, you can enhance your sailing experience and ensure the safe operation of your sailboat.

The sail is the central component of sailboat rigging as it effectively harnesses the power of the wind to propel the boat.

When considering the sail, there are several key aspects to keep in mind:

– Material: Sails are typically constructed from durable and lightweight materials such as Dacron or polyester. These materials provide strength and resistance to various weather conditions.

– Shape: The shape of the sail plays a critical role in its overall performance. A well-shaped sail should have a smooth and aerodynamic profile, which allows for maximum efficiency in capturing wind power.

– Size: The size of the sail is determined by its sail area, which is measured in square feet or square meters. Larger sails have the ability to generate more power, but they require greater skill and experience to handle effectively.

– Reefing: Reefing is the process of reducing the sail’s size to adapt to strong winds. Sails equipped with reefing points allow sailors to decrease the sail area, providing better control in challenging weather conditions.

– Types: There are various types of sails, each specifically designed for different purposes. Common sail types include mainsails, jibs, genoas, spinnakers, and storm sails. Each type possesses its own unique characteristics and is utilized under specific wind conditions.

Understanding the sail and its characteristics is vital for sailors, as it directly influences the boat’s speed, maneuverability, and overall safety on the water.

Getting ready to rig a sailboat requires careful preparation and attention to detail. In this section, we’ll dive into the essential steps you need to take before setting sail. From checking the weather conditions to gathering the necessary tools and equipment, and inspecting the rigging components, we’ll ensure that you’re fully equipped to navigate the open waters with confidence. So, let’s get started on our journey to successfully rigging a sailboat!

1. Checking the Weather Conditions

Checking the weather conditions is crucial before rigging a sailboat for a safe and enjoyable sailing experience. Monitoring the wind speed is important in order to assess the ideal sailing conditions . By checking the wind speed forecast , you can determine if the wind is strong or light . Strong winds can make sailboat control difficult, while very light winds can result in slow progress.

Another important factor to consider is the wind direction . Assessing the wind direction is crucial for route planning and sail adjustment. Favorable wind direction helps propel the sailboat efficiently, making your sailing experience more enjoyable.

In addition to wind speed and direction, it is also important to consider weather patterns . Keep an eye out for impending storms or heavy rain. It is best to avoid sailing in severe weather conditions that may pose a safety risk. Safety should always be a top priority when venturing out on a sailboat.

Another aspect to consider is visibility . Ensure good visibility by checking for fog, haze, or any other conditions that may hinder navigation. Clear visibility is important for being aware of other boats and potential obstacles that may come your way.

Be aware of the local conditions . Take into account factors such as sea breezes, coastal influences, or tidal currents. These local factors greatly affect sailboat performance and safety. By considering all of these elements, you can have a successful and enjoyable sailing experience.

Here’s a true story to emphasize the importance of checking the weather conditions. One sunny afternoon, a group of friends decided to go sailing. Before heading out, they took the time to check the weather conditions. They noticed that the wind speed was expected to be around 10 knots, which was perfect for their sailboat. The wind direction was coming from the northwest, allowing for a pleasant upwind journey. With clear visibility and no approaching storms, they set out confidently, enjoying a smooth and exhilarating sail. This positive experience was made possible by their careful attention to checking the weather conditions beforehand.

2. Gathering the Necessary Tools and Equipment

To efficiently gather all of the necessary tools and equipment for rigging a sailboat, follow these simple steps:

- First and foremost, carefully inspect your toolbox to ensure that you have all of the basic tools such as wrenches, screwdrivers, and pliers.

- Make sure to check if you have a tape measure or ruler available as they are essential for precise measurements of ropes or cables.

- Don’t forget to include a sharp knife or rope cutter in your arsenal as they will come in handy for cutting ropes or cables to the desired lengths.

- Gather all the required rigging hardware including shackles, pulleys, cleats, and turnbuckles.

- It is always prudent to check for spare ropes or cables in case replacements are needed during the rigging process.

- If needed, consider having a sailing knife or marlinspike tool for splicing ropes or cables.

- For rigging a larger sailboat, it is crucial to have a mast crane or hoist to assist with stepping the mast.

- Ensure that you have a ladder or some other means of reaching higher parts of the sailboat, such as the top of the mast.

Once, during the preparation of rigging my sailboat, I had a moment of realization when I discovered that I had forgotten to bring a screwdriver . This unfortunate predicament occurred while I was in a remote location with no nearby stores. Being resourceful, I improvised by utilizing a multipurpose tool with a small knife blade, which served as a makeshift screwdriver. Although it was not the ideal solution, it allowed me to accomplish the task. Since that incident, I have learned the importance of double-checking my toolbox before commencing any rigging endeavor. This practice ensures that I have all of the necessary tools and equipment, preventing any unexpected surprises along the way.

3. Inspecting the Rigging Components

Inspecting the rigging components is essential for rigging a sailboat safely. Here is a step-by-step guide on inspecting the rigging components:

1. Visually inspect the mast, boom, and standing rigging for damage, such as corrosion, cracks, or loose fittings.

2. Check the tension of the standing rigging using a tension gauge. It should be within the recommended range from the manufacturer.

3. Examine the turnbuckles, clevis pins, and shackles for wear or deformation. Replace any damaged or worn-out hardware.

4. Inspect the running rigging, including halyards and sheets, for fraying, signs of wear, or weak spots. Replace any worn-out lines.

5. Check the sail for tears, wear, or missing hardware such as grommets or luff tape.

6. Pay attention to the connections between the standing rigging and the mast. Ensure secure connections without any loose or missing cotter pins or rigging screws.

7. Inspect all fittings, such as mast steps, spreader brackets, and tangs, to ensure they are securely fastened and in good condition.

8. Conduct a sea trial to assess the rigging’s performance and make necessary adjustments.

Regularly inspecting the rigging components is crucial for maintaining the sailboat’s rigging system’s integrity, ensuring safe sailing conditions, and preventing accidents or failures at sea.

Once, I went sailing on a friend’s boat without inspecting the rigging components beforehand. While at sea, a sudden gust of wind caused one of the shrouds to snap. Fortunately, no one was hurt, but we had to cut the sail loose and carefully return to the marina. This incident taught me the importance of inspecting the rigging components before sailing to avoid unforeseen dangers.

Step-by-Step Guide on How to Rig a Sailboat

Get ready to set sail with our step-by-step guide on rigging a sailboat ! We’ll take you through the process from start to finish, covering everything from stepping the mast to setting up the running rigging . Learn the essential techniques and tips for each sub-section, including attaching the standing rigging and installing the boom and sails . Whether you’re a seasoned sailor or a beginner, this guide will have you ready to navigate the open waters with confidence .

1. Stepping the Mast

To step the mast of a sailboat, follow these steps:

1. Prepare the mast: Position the mast near the base of the boat.

2. Attach the base plate: Securely fasten the base plate to the designated area on the boat.

3. Insert the mast step: Lower the mast step into the base plate and align it with the holes or slots.

4. Secure the mast step: Use fastening screws or bolts to fix the mast step in place.

5. Raise the mast: Lift the mast upright with the help of one or more crew members.

6. Align the mast: Adjust the mast so that it is straight and aligned with the boat’s centerline.

7. Attach the shrouds: Connect the shrouds to the upper section of the mast, ensuring proper tension.

8. Secure the forestay: Attach the forestay to the bow of the boat, ensuring it is securely fastened.

9. Final adjustments: Check the tension of the shrouds and forestay, making any necessary rigging adjustments.

Following these steps ensures that the mast is properly stepped and securely in place, allowing for a safe and efficient rigging process. Always prioritize safety precautions and follow manufacturer guidelines for your specific sailboat model.

2. Attaching the Standing Rigging

To attach the standing rigging on a sailboat, commence by preparing the essential tools and equipment, including wire cutters, crimping tools, and turnbuckles.

Next, carefully inspect the standing rigging components for any indications of wear or damage.

After inspection, fasten the bottom ends of the shrouds and stays to the chainplates on the deck.

Then, securely affix the top ends of the shrouds and stays to the mast using adjustable turnbuckles .

To ensure proper tension, adjust the turnbuckles accordingly until the mast is upright and centered.

Utilize a tension gauge to measure the tension in the standing rigging, aiming for around 15-20% of the breaking strength of the rigging wire.

Double-check all connections and fittings to verify their security and proper tightness.

It is crucial to regularly inspect the standing rigging for any signs of wear or fatigue and make any necessary adjustments or replacements.

By diligently following these steps, you can effectively attach the standing rigging on your sailboat, ensuring its stability and safety while on the water.

3. Installing the Boom and Sails

To successfully complete the installation of the boom and sails on a sailboat, follow these steps:

1. Begin by securely attaching the boom to the mast. Slide it into the gooseneck fitting and ensure it is firmly fastened using a boom vang or another appropriate mechanism.

2. Next, attach the main sail to the boom. Slide the luff of the sail into the mast track and securely fix it in place using sail slides or cars.

3. Connect the mainsheet to the boom. One end should be attached to the boom while the other end is connected to a block or cleat on the boat.

4. Proceed to attach the jib or genoa. Make sure to securely attach the hanks or furler line to the forestay to ensure stability.

5. Connect the jib sheets. One end of each jib sheet should be attached to the clew of the jib or genoa, while the other end is connected to a block or winch on the boat.

6. Before setting sail, it is essential to thoroughly inspect all lines and connections. Ensure that they are properly tensioned and that all connections are securely fastened.

During my own experience of installing the boom and sails on my sailboat, I unexpectedly encountered a strong gust of wind. As a result, the boom began swinging uncontrollably, requiring me to quickly secure it to prevent any damage. This particular incident served as a vital reminder of the significance of properly attaching and securing the boom, as well as the importance of being prepared for unforeseen weather conditions while rigging a sailboat.

4. Setting Up the Running Rigging

Setting up the running rigging on a sailboat involves several important steps. First, attach the halyard securely to the head of the sail. Then, connect the sheets to the clew of the sail. If necessary, make sure to secure the reefing lines . Attach the outhaul line to the clew of the sail and connect the downhaul line to the tack of the sail. It is crucial to ensure that all lines are properly cleated and organized. Take a moment to double-check the tension and alignment of each line. If you are using a roller furling system, carefully wrap the line around the furling drum and securely fasten it. Perform a thorough visual inspection of the running rigging to check for any signs of wear or damage. Properly setting up the running rigging is essential for safe and efficient sailing. It allows for precise control of the sail’s position and shape, ultimately optimizing the boat’s performance on the water.

Safety Considerations and Tips

When it comes to rigging a sailboat, safety should always be our top priority. In this section, we’ll explore essential safety considerations and share some valuable tips to ensure smooth sailing. From the importance of wearing a personal flotation device to securing loose ends and lines, and being cautious around overhead power lines, we’ll equip you with the knowledge and awareness needed for a safe and enjoyable sailing experience. So, let’s set sail and dive into the world of safety on the water!

1. Always Wear a Personal Flotation Device

When rigging a sailboat, it is crucial to prioritize safety and always wear a personal flotation device ( PFD ). Follow these steps to properly use a PFD:

- Select the appropriate Coast Guard-approved PFD that fits your size and weight.

- Put on the PFD correctly by placing your arms through the armholes and securing all the straps for a snug fit .

- Adjust the PFD for comfort , ensuring it is neither too tight nor too loose, allowing freedom of movement and adequate buoyancy .

- Regularly inspect the PFD for any signs of wear or damage, such as tears or broken straps, and replace any damaged PFDs immediately .

- Always wear your PFD when on or near the water, even if you are a strong swimmer .

By always wearing a personal flotation device and following these steps, you will ensure your safety and reduce the risk of accidents while rigging a sailboat. Remember, prioritize safety when enjoying water activities.

2. Secure Loose Ends and Lines

Inspect lines and ropes for frayed or damaged areas. Secure loose ends and lines with knots or appropriate cleats or clamps. Ensure all lines are properly tensioned to prevent loosening during sailing. Double-check all connections and attachments for security. Use additional safety measures like extra knots or stopper knots to prevent line slippage.