The global authority in superyachting

- NEWSLETTERS

- Yachts Home

- The Superyacht Directory

- Yacht Reports

- Brokerage News

- The largest yachts in the world

- The Register

- Yacht Advice

- Yacht Design

- 12m to 24m yachts

- Monaco Yacht Show

- Builder Directory

- Designer Directory

- Interior Design Directory

- Naval Architect Directory

- Yachts for sale home

- Motor yachts

- Sailing yachts

- Explorer yachts

- Classic yachts

- Sale Broker Directory

- Charter Home

- Yachts for Charter

- Charter Destinations

- Charter Broker Directory

- Destinations Home

- Mediterranean

- South Pacific

- Rest of the World

- Boat Life Home

- Owners' Experiences

- Interiors Suppliers

- Owners' Club

- Captains' Club

- BOAT Showcase

- Boat Presents

- Events Home

- World Superyacht Awards

- Superyacht Design Festival

- Design and Innovation Awards

- Young Designer of the Year Award

- Artistry and Craft Awards

- Explorer Yachts Summit

- Ocean Talks

- The Ocean Awards

- BOAT Connect

- Between the bays

- Golf Invitational

- Boat Pro Home

- Pricing Plan

- Superyacht Insight

- Product Features

- Premium Content

- Testimonials

- Global Order Book

- Tenders & Equipment

.jpg/r%5Bwidth%5D=320/c01b08f0-3198-11ec-b3da-5dc06521023f-Black%20Pearl%20-%20Tom%20Van%20Oossanen%20(3).webp)

The definitive guide to sailing yacht rigging

Related articles, superyacht directory.

Do you know your Bermudan rig from your DynaRig or wingsails? And which is best? BOAT explains it all...

Take a look at a modern racing yacht from above, beating to windward and heeled to the breeze, and you can see at a glance why Bermudan rigs have stood the test of time. With its fore and aft sails bladed into efficient aerodynamic shapes, a modern yacht can slice close to the wind and be driven hard. Such a sight would have been outlandish a century ago. Then, a typical trading barquentine could set 18 sails to catch light airs, but it needed a large crew to battle with canvas far out on the yards. In a modern miracle as incredible in its way as flight, today’s racing yachts can sail faster than the speed of the wind – in some cases several times faster.

A mainsail set on a single spar is an age-old concept but only in the 19th century was it adapted as the Bermudan or Marconi rig. A one-piece mainsail set on a mast without a gaff, hoisted with one halyard and controlled by one sheet, was simpler and more efficient. This revolution became the power train of pleasure yachting and racing.

But perhaps the time is coming for a re-evaluation of simpler rigs requiring fewer crew – alternatives with lower loads operated by automated systems. In an era of reduced carbon consumption, could more radical sailplans even herald a revival in sail power?

The evergreen Bermudan rig

The Bermudan rig is the all-rounder, able to perform well at all angles of sail. It is efficient upwind, while downwind the sail area can be significantly boosted with a big gennaker or spinnaker. For good reasons, it is the first choice for nearly every modern sailing yacht up to around 60 to 65 metres for cruising and regatta racing alike. At larger sizes, however, things start to become trickier, and the trade-offs get interesting.

Over the last decade, sail handling technology has steadily advanced to allow sloop rigs to grow larger and larger. “But with that comes a highly loaded rig, many tonnes of compression from tension in the rigging, and you have to build structure in the boat to accept that,” explains Paul MacDonald, founder and superyacht sales manager of Southern Spars.

“You have to have a lot of deck gear and captive winches below decks and the machinery for that. But over the years, boom furling systems and MPS [Multi Purpose Sails for downwind angles] stored on a drum, for example, have made sail handling safer.

Bill Tripp is the designer behind the 86-metre Aquijo , which broke new ground in 2015 as the world’s largest Bermudan ketch. Tripp prefers to call the rig a "sketch", a portmanteau word for a rig that is neither a sloop nor a ketch “because the main and mizzen are identical”. Even though the sailplan is divided over two masts, each spar is still a towering 90 metres above the water. Aquijo perfectly illustrates the issues involved with a Bermudan rig when scaled up.

“The sloop is great but I prefer the ‘sketch’ for sailing around the world under full control due to the desirability of a two-masted rig for reaching ability, which dominates passages, and the safety of controllable loads when sailing in all kinds of conditions miles from nowhere,” he says.

Upwind, Aquijo sets a jib, staysail, mainsail and mizzen, all in North Sails 3Di, totalling 3,821 square metres. A furling Code sail for reaching and downwind angles increases that to a vast 5,051 square metres.

While Aquijo has a crew retinue of 17, it can be controlled under sail by six or seven people. With custom winches to handle halyards and sheets, the sails can be hoisted astonishingly quickly for such a large rig. “It takes five minutes to put the main up, on average, and the main and mizzen can go up at the same time,” Tripp says. Aquijo has now sailed 100,000 nautical miles around the world and the owner is planning another circumnavigation through the Northwest Passage.

Tripp is not convinced of the wisdom of a much larger single-masted sloop rig. “If you are day sailing in the Med, a sloop would be awesome, but I am not sure if you had fewer sails you would be able to [reduce canvas] well enough. Also the mast is a windage problem when the keel is up and you are beam-to. If you are on anchor, that’s no problem but you’d have to be able to cope with being on the docks in 70 knots. The windage at 120 metres is not only more but the centre of effort is so much higher, and so the heeling loads all go up.”

However, British designer Malcolm McKeon , the name behind the high-performance, sloop-rigged carbon composite superyachts Missy and Ribelle , is pushing the sloop rig to new heights. His 85-metre design concept Apex, developed with Royal Huisman , would be the largest sloop-rigged yacht in the world. “The loads are enormous,” he admits, “but it is all scalable.”

“The big disadvantage is sail handling. The downwind sails are pretty complicated once you start hoisting and retrieving, even with drum and reel systems. It is not straightforward.” But, he adds, “I think we know the advantages of a sloop: if you want all-round performance you can’t beat it, even at the top end.”

Advantages of a clipper rig

The DynaRig has been around as a concept since the 1960s when German engineer Wilhelm Prölss devised these free-standing, rotating rigs as a fuel-saving solution for large commercial vessels. The idea was ahead of its time, so much so that its first realisation came nearly 40 years later when American owner Tom Perkins bought the residual technology and commissioned Dykstra Naval Architects to create a three-masted DynaRig for Maltese Falcon , his 88-metre Perini Navi.

The DynaRig is not as efficient upwind as the Bermudan rig, and is probably not the best solution for a yacht smaller than around 65 metres, suggests Jeroen de Vos of Dykstra. “We wouldn’t advise putting a DynaRig on a small yacht because there are other ways to manage sail handling. But on a larger yacht the DynaRig becomes an alternative because there is no rigging, no highly loaded sheets, low-tech [small] sails and no big winches.”

The beauty of the DynaRig is that its automatic systems can be handled by one or two people and, notes de Vos, “you don’t have to get out of your chair to go sailing. Maltese Falcon can sail on and off the anchor and can set 2,400 square metres of sail in six minutes. On other boats it takes six minutes to get the sail cover off.”

Damon Roberts of Magma Structures, which built the rigs for Maltese Falcon and the only other DynaRig yacht to date, the 106-metre Black Pearl , says: “You can do any manoeuvre easily; it’s like sailing a dinghy. There are no highly loaded sheets or ropes or flogging lines. You can luff up, bear away, tack and gybe at any time and really enjoy sailing the boat without any apparent fuss.”

So with all these advantages, why has the DynaRig been chosen for only two sailing superyachts? For some designers, such as Malcolm McKeon, it is partly to do with compromises imposed by the large mast tubes and bearing diameters on the internal structure and layout, “particularly in the cockpit area,” he says. He also points out that the clipper ship look is not to every owner’s taste. “Sloops are more conventional looking,” he says.

Damon Roberts says there is still development work to be done. He has teamed up with Southern Spars and, with their additional resources, expects evolution with several new projects. “These include two at the moment that are twin-masted DynaRigs,” he says. “We did quite a lot of wind tunnel work early on as we felt that was really the sweet spot for it, and people will be stunned at how efficient these are.”

The future of the wingsail

Wingsails have been around for decades too, but with their adoption by the last two America’s Cups and the confluence with foiling technology, they have undergone rapid and revolutionary development.

To date, there is no proven solution for reefing a wing that would be suitable for offshore cruising or ocean passages. As the pronounced aerodynamic “nose” at the leading edge of a wing can develop force in strong winds, they could potentially make a large yacht uncontrollable in port as well.

“How do you get rid of sail and how does [a boat] handle when caught out in heavy wind conditions – which you will be? How do you keep the angle of attack all the way up the rig and how do you handle squalls?” Roberts asks. “A mechanism to reduce sail might be easy to sketch out but it is difficult to engineer.”

Jeroen de Vos says: “The wingsails are more developed towards performance and I wouldn’t say that they are as practical as soft sails or would ever make handling easier. But if somebody wants that, why not? Reefable soft sails, wings that are inflated, hoisted panels, possibly these are applicable. The development of this area is happening very rapidly.”

Paul MacDonald of Southern Spars agrees that the time is not here yet but thinks it will come. “In reality we are in the early days of wings. For the America’s Cup, they are the most efficient way of sailing by a long shot, but with them comes handling issues, which the industry hasn’t resolved yet. But I am sure they will be in 10 years’ time. Designers such as VPLP are starting to [work on concepts] and we are going to see something that is usable and efficient and suitable for ocean work eventually,” he says. “And whatever the solution is, you imagine that it will scale.”

Looking to the future

A drive for greener superyachts could present an opportunity for sail, but perhaps it needs to be less daunting.

“There is this intimidation of sheets and backstays, and sailing is a language you don’t learn in a year,” Tripp says. “But we have a project we are doing now with a yard with some new rig technology and some soft wings that we think is going to be viable.

“We can uncomplicate sailing more. If we can win people over from motorboats it will help, but we are only winning these battles one or two at a time. We need [more] projects like Sailing Yacht A , which are something really different, and do more things better with less energy. We as architects need to elicit change.”

McKeon also sees change coming. “People are more and more concerned about keeping their image green and sails are the way to do that,” he says. “Simpler sailing systems are needed. The current generation is used to Bermudan sloops. In years to come, the traditionalists will all be gone, and maybe new people will be more accepting of [different ideas]. I think in the future we will certainly have wings.”

More about this yacht

Yachts for sale, similar yachts for sale, yachts for charter, more stories, most popular, from our partners, sponsored listings.

- BOAT OF THE YEAR

- Newsletters

- Sailboat Reviews

- Boating Safety

- Sailing Totem

- Charter Resources

- Destinations

- Galley Recipes

- Living Aboard

- Sails and Rigging

- Maintenance

- Best Marine Electronics & Technology

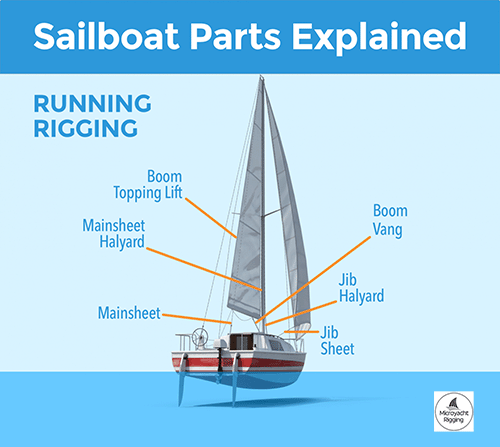

Understanding Running Rigging

- By Ralph Naranjo

- Updated: January 22, 2020

Regardless of whether you sail a modern, fractional-rigged sloop or a wishbone-rigged staysail schooner, it’s the running rigging that sets, trims, reefs and furls the sails. In the bad old days, decks were full of wobbly, sheaved high-friction blocks and essentially one kind of cordage. Today, running rigging has attained full-system status, with its primary goal being friction abatement.

Various types of synthetic- fiber cordage, with specific strength, stretch and creep characteristics, run through ultraslippery blocks and fairleads. Each line is aimed at the exact spot a team of ergonomics experts determined it should go. Even the halyard hardware that attaches the line to the head of a sail has been computer-modeled and scrutinized with finite element analysis. Soft shackles and strops, made from Dyneema fiber rope, are showing up in high-load locations. In short, we are in the midst of a running-rigging revolution, and much of the new stuff offers real value to the cruising sailor.

What’s My Line?

Just as pistons and cylinders play a primary role in a diesel auxiliary, rope and blocks are the guts of every sail-handling system. A few decades ago, Dacron (polyester cordage) ruled the roost. It remains a key player, but stronger, lighter, and less-stretchy options are gaining ground. Racers have embraced Dyneema, Vectran, Torlon, Zylon and a growing list of other odd-sounding esoteric fibers. The old enemy stretch has been tamed, but the big remaining question is whether a running-rigging makeover is worth the expense. It takes a little cost-benefit analysis to answer that question.

There’s consensus among sailors, riggers and yacht designers that there are cost-effective crossover points, where performance and value intersect. Take, for example, a mainsail halyard upgrade. Polyester has proved to be too stretchy, but PBO (Zylon) cored rope, sometimes called liquid crystal, is way too costly. But for cruisers, a midrange medium-tech upgrade makes a lot of sense. The line of choice is often a double braid with a high-modulus Dyneema core and a conventional polyester cover. This midrange combo results in a halyard with much lower stretch and good handling characteristics, plus it retains a chafe- and ultraviolet-resistant cover.

Going higher-tech in fiber selection for sheets on a cruising boat might not be as desirable. This is because a good-quality double-braid polyester remains a sensible solution, at least on cruising boats under 40 or so feet. Its stretchy nature might even add a little shock-absorber effect, lessening the fatigue cycle on mast, boom and line. However, higher-modulus (less-stretchy) line is a superior halyard material, and it also makes sense for use in running backstays, topping lifts, tack and head pennants, and boom-vang tackles.

When choosing the right high-modulus line, make sure it’s rated for tight turns around small-radius blocks and masthead sheaves. In the early days of synthetic fibers, many ultra-low-stretch lines stiffened with time, making line handling more like wrapping a tree branch around a winch drum. Today, Samson, Yale, New England Ropes and others have tamed this problem, and offer a wide range of products that meet the needs of cruisers and racers. Do some research, talk with a local rigger, and pick the right rope for your boat and your specific sailing requirements.

Around the Blocks

Every ball- and roller-bearing block spins like a roulette wheel when there’s no load on the sheave. But when you add hundreds, even thousands, of pounds of tension to a halyard or sheet, it’s only the better-built blocks that hold friction at bay. Usually these blocks have well-engineered frames and bearing races that resist deformation under heavy loads.

Ironically, cruisers don’t need the highest-tech line, but we certainly do benefit from the best-built blocks. These not only run smoothly under load, but they also continue to do so despite the test of time.

Over the years, as ingested salt spray is baked into grit by the unrelenting sun, bearing abrasion becomes a big problem. Keep in mind that if you can see the high-molecular-weight Delrin, Torlon or other plastic bearings, so can the sun, and this means that UV degradation will become an issue.

It’s also important to recognize that choosing the smallest, lightest block for a given line size makes little sense. A better approach is to pick a one-size-larger block that’s still appropriate for the given line diameter. It will deliver a higher safe working load, and therefore, the normal load will be a smaller percentage of the SWL. Such blocks will also have a larger bearing surface and will operate with less friction. Add to this the fact that lower loading also equates to longer hardware life, and you have another good reason to opt for a size uptick.

Power to the Winches

I think that the hand-crank winch is one of sailing’s most elegant inventions. And the good news is this piece of hardware continues to evolve. New designs come packed with better bearings, improved self-tailers and multiple gear ratios, making them even better muscle-power multipliers.

Modern winches are more ergonomic, and there’s even a model that lets you trim in and ease out via opposite rotations of the winch handle. The shorthanded cruiser has more trimming tools from which to choose—even a push-button electric winch that eliminates the old question: “Where’s the winch handle?”

However, when it comes to power winching, it’s important to rethink the way you handle a sheet or halyard. With the old hand-cranking approach, arm and shoulder strength provided both torque and feedback. Unfortunately, this feedback loop is absent when using an electric winch. As the tension increases, the button doesn’t get any harder to push. Therefore, we need to look more closely at the luff and head of the sail to make sure the halyard or sheet is not being overtensioned.

In the early days of power winches, I watched the crew of a 60-foot sloop set sail with the aid of electric winches. As the mainsail was being unfurled, the furling line hung up, causing the tension on the outhaul to reach full force in the matter of a second or two. A loud bang announced the separation of the clew from the mainsail. It was an attention-grabbing demonstration of the brute force delivered by a power winch—and a costly lesson in how high-modulus, low-stretch materials endure minimal elongation prior to failure. The takeaway from this episode was that careful attention must be paid to the line being tensioned and what’s happening to the sail. Beware of dodgers and Biminis that hide the sails from view and leave the person operating a power winch without any direct visual feedback.

Clutch Plays

Some see the self-tailing winch as the ultimate answer to handling a line under load. But there are other opinions that continue to hold sway. The oldest belongs to traditionalists who swear by horn cleats, just the way Nat Herreshoff intended. It’s a functional approach, especially if the deck is festooned with non-self-tailing winches that remain in good working order.

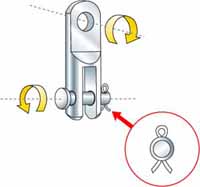

But we are in a rope-clutch revolution that’s realigned deck layouts and changed the approach to line handling. These lever-operated, clamplike devices allow one winch to cope with several lines, but not all at once. With badgerlike jaws, rope clutches lock lines in place, immobilizing the line under full load. Some clutches allow a sailor to release the fully tensioned line, but lines under load behave more sedately if, prior to releasing, they are wrapped on the winch and re-tensioned prior to releasing the clutch. The line is then eased from the winch drum.

There’s a fine art to making the right rope-clutch commitment. The “too much of a good thing” rule once again prevails, and surrounding a winch with four or five clutched lines can cause more problems than it solves. This is especially true if two or more heavily loaded lines are involved in the same sail-handling evolution. I’ve sailed on boats where a main halyard and mainsheet are clutched off at the same winch. The assumption is that once the sail is set, the halyard will remain locked in the clutch and the winch can be used to handle the sheet. All is copacetic up until it’s time to reef, and the mainsheet and halyard have to be handled with only one winch. Add darkness, a significant seaway and a crew just rousted from a deep sleep, and the value of an extra winch, rather than too many rope clutches, becomes very clear.

Furling systems are center stage aboard modern cruising sailboats. They make sail handling easier and safer because the majority of maneuvers can take place in the cockpit.

Headstay-mounted headsail furlers adorn almost every sailboat seen at in-water boat shows. They come in two distinct generic designs. Both types are comprised of a slotted alloy extrusion that fits over the headstay. A jib or genoa is initially hoisted via a rope halyard, then torque to wind in the sail is provided by a drum affixed to the bottom end of the foil. The difference between the two systems is that one relies on a mast-mounted sheave that leads a jib halyard to a sliding swivel that rides up and down the foil. The other system, usually found on smaller boats, has a sheave assembly affixed to the top foil section and the halyard(s) is not run to the mast. Owners with the latter system often continually fight the stretchiness of the small-diameter polyester line used for the halyard. Switching to a higher-modulus (less-stretchy) line lessens the stretch and is worth the investment.

Both systems rely on a spooled line to deliver the furling and reefing torque. This “in-haul” line endures years of UV and chafe damage, but at some point, failure becomes inevitable. It’s more likely to occur when the sail is reefed and the inhaul line is under significant load. For some reason, such failures seem to occur on a dark, rainy night at about 0300. And when a reefing line parts, the deeply reefed jib becomes a full genoa flogging like a flag in the breeze. Even worse, the line to haul it in is no longer usable. That’s why it makes sense to check for chafe and grow skeptical of a furling line that has been exposed to sunlight for more than a decade.

Endless or continuous line furlers are designed to tame large drifter/reachers and nylon asymmetric spinnakers. There are bottom-up and top-down versions, and each is designated by where the sail first begins to furl. Bottom-up furlers are used for light air, lightweight genoa-like sails (codes and reaching sails). Instead of furling with a fishing-reel-like drum arrangement, these endless line furlers rely on a continuous loop. Line tension turns into torque at the disk-shaped drum that holds only a partial turn of line. The twin leads of the elongated loop can be led aft to the cockpit via multiple sets of double blocks mounted on lifeline stanchions.

Asymmetric spinnakers utilize a top-down furling rotation that is telegraphed from the drum to the head of the sail using a torsion line. The splices on these endless-loop furling lines should be regularly checked, and so should the points where the torsion rope enters the hardware.

Cordage—like the hardware that leads and locks running rigging in place—has been vastly improved, and it makes sense for sailors to tap into what it has to offer. This can be done in a full-scale makeover or in a bit-at-a-time tuneup. With the latter, start with halyards, add some new blocks, and check or replace the mast sheaves. If winches and clutches are part of the redo, make sure the deck structure can handle the load, or have some extra reinforcement added.

Whatever the scale of the rigging refit, keep in mind that on a cruising boat, saving ounces isn’t the issue. Our goal is to add efficiency and reliability, and that involves picking hardware and cordage with the right specs, and using them in a layout that keeps the rigging running as friction-free as possible.

Technical expert Ralph Naranjo is a veteran circumnavigator and ocean racer, and author of The Art of Seamanship .

- More: hardware , How To , print 2020 winter , rigging

- More How To

How to Protect Your Spars from Corrosion

Sailing totem refit series: the forward head makeover, fatty goodlander: dealing with chafe while cruising, how to rig everything in your favor, route planning in the face of climate change.

- Digital Edition

- Customer Service

- Privacy Policy

- Email Newsletters

- Cruising World

- Sailing World

- Salt Water Sportsman

- Sport Fishing

- Wakeboarding

- Boat Rigging: Setting Sail for Success

In the world of sailing, boat rigging plays a crucial role in ensuring the safety, efficiency, and performance of your vessel. From standing rigging to sail rigging types, it's essential to understand the intricacies of rigging a yacht to embark on smooth sailing adventures. In this comprehensive guide, we'll dive into the nuances of boat rigging, helping you navigate the open waters with confidence.

Boat Rigging Basics

Before we delve into the details, let's start with the fundamentals of boat rigging. Understanding the key components and their functions is essential for any sailor, whether you're a novice or a seasoned pro.

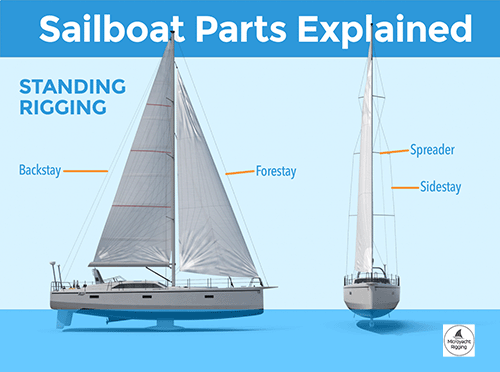

Standing Rigging

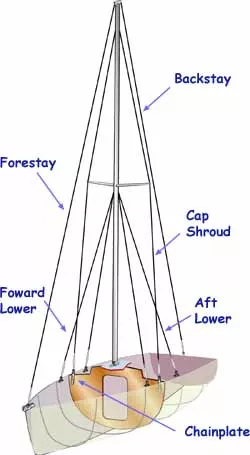

Standing rigging refers to the fixed support structure of a boat's mast, including wires, cables, and rods. It plays a critical role in maintaining the mast's vertical position and overall stability.

Sail Rigging Types

Sail rigging is not a one-size-fits-all concept, but rather a diverse world with various types and configurations to suit different sailing needs. Understanding these rigging types is essential for any sailor looking to optimize their boat's performance and safety.

Ship Riggings

Ship riggings have played a pivotal role in shaping the history of seafaring and maritime exploration. These complex systems of ropes, wires, and sails have been integral to the functionality and success of various vessels throughout the ages.Explore the significance of ship riggings, their evolution, and their influence on modern-day boat rigging.

Materials Matter

The choice of materials for your boat rigging is a decision that can't be taken lightly. Two popular options, Dyneema and Kevlar, offer distinct advantages.

Dyneema Rigging

Dyneema rigging represents a breakthrough in the world of sailboat rigging. This cutting-edge material, known for its remarkable strength and low stretch properties, has revolutionized the way sailors experience the open water. Often referred to as the ultimate innovation in the world of sailing, Dyneema rigging offers a myriad of advantages:

- Exceptional Strength: Dyneema rigging boasts remarkable strength-to-weight ratio, making it incredibly robust and reliable even in demanding conditions.

- Low Stretch: Dyneema has minimal stretch, which translates to improved sail control and responsiveness, ensuring better performance.

- Lightweight: It's significantly lighter than traditional rigging materials like steel, reducing the overall weight of your vessel and enhancing speed and maneuverability.

- Low Maintenance: Dyneema rigging requires minimal maintenance, offering sailors peace of mind and more time on the water.

- Resistance to Corrosion: Unlike metal rigging, Dyneema is not susceptible to corrosion, ensuring a longer lifespan and durability.

- UV Resistance: Dyneema is highly resistant to UV rays, making it ideal for prolonged exposure to sunlight.

- Easy Handling: Its flexibility and ease of handling simplify rigging installation and adjustments.

- Enhanced Safety: Dyneema's strength and reliability contribute to safer sailing experiences, reducing the risk of rigging failure.

- Versatility: It's suitable for a wide range of applications, from standing rigging to halyards, making it a versatile choice for sailors.

- Eco-Friendly: Dyneema is an environmentally friendly option as it doesn't release harmful substances into the water, contributing to a cleaner marine ecosystem.

Dyneema vs. Kevlar

Weigh the pros and cons of Dyneema and Kevlar to determine which suits your sailing needs best:

Dyneema Rigging:

- Exceptional Strength: Dyneema boasts impressive strength, making it highly reliable for rigging purposes.

- Low Stretch: It has minimal stretch, enhancing sail control and overall performance.

- Lightweight: Dyneema is significantly lighter than traditional materials, reducing the vessel's weight.

- Low Maintenance: Requires minimal upkeep, saving time and effort.

- Corrosion Resistance: Dyneema is not susceptible to corrosion, ensuring durability.

- UV Resistance: It's highly resistant to UV rays, making it suitable for extended exposure to sunlight.

- Safety: Dyneema's strength and reliability contribute to safer sailing experiences.

- Versatility: Suitable for various rigging applications, from standing rigging to halyards.

- Cost: Dyneema can be more expensive than some traditional materials, initially.

- Abrasion Resistance: It may be less resistant to abrasion compared to Kevlar.

Kevlar Rigging:

- Excellent Abrasion Resistance: Kevlar is highly resistant to wear and tear, ensuring longevity.

- High Tensile Strength: It offers impressive tensile strength, making it suitable for demanding applications.

- Stiffness: Kevlar is stiffer than Dyneema, which can be advantageous for some rigging configurations.

- Heavy: Kevlar is heavier than Dyneema, potentially impacting vessel performance.

- Low UV Resistance: It is less resistant to UV radiation, which can affect its durability over time.

- Higher Stretch: Kevlar tends to stretch more than Dyneema, which can impact sail control.

- Prone to Corrosion: Unlike Dyneema, Kevlar can be susceptible to corrosion.

- Cost: It can be expensive, and the initial investment may be higher than other materials.

Choosing between Dyneema and Kevlar depends on your specific sailing needs and priorities. Dyneema is favored for its strength, low stretch, and light weight, while Kevlar excels in abrasion resistance and tensile strength. Consider these factors when making your rigging material selection.

Stainless Steel Yacht Rigging

When it comes to yacht rigging, durability is paramount, and stainless steel rigging wires stand out as a top choice. Their robust nature, coupled with an unmistakable touch of elegance, makes them an ideal option for discerning sailors. Stainless steel yacht rigging is highly resistant to corrosion, even in the harsh marine environment. This resistance not only ensures a longer lifespan but also reduces maintenance efforts, allowing you to spend more time on the water. Additionally, the sleek appearance of stainless steel adds a touch of sophistication to your vessel. Whether you're cruising the open seas or participating in regattas, stainless steel yacht rigging combines style and substance to offer a premium sailing experience.

Spectra Standing Rigging

Spectra standing rigging is a game-changer for sailors seeking top-tier performance and durability. This advanced material, known for its incredible strength and low stretch properties, has revolutionized the way we approach standing rigging. Spectra rigging offers advantages that are hard to beat – it enhances the stability and safety of your vessel while providing exceptional responsiveness. The minimal stretch ensures precise sail control, making it the go-to choice for those who demand the utmost from their rigging. If you're looking to take your sailing experience to the next level, Spectra standing rigging is a choice that can't be ignored.

Read our top notch articles on topics such as sailing, sailing tips and destinations in our Magazine.

Rigging a Yacht: A Step-By-Step Guide

Now that you've grasped the basics and material options, let's dive into the practical aspect of rigging a yacht. Follow these steps to ensure a smooth and safe sailing experience.

Planning and Preparation

Rigging a yacht is a meticulous process that requires careful planning and thorough preparation. Before embarking on your sailing adventure, it's crucial to ensure that every aspect of your yacht's rigging is in top-notch condition. The advantages of this step-by-step guide are manifold. It guarantees the safety of both the vessel and its passengers, reduces the risk of mid-sail complications, and ultimately enhances your overall sailing experience. By meticulously inspecting your rigging and addressing any issues during the planning and preparation phase, you can set sail with confidence, knowing that your yacht is ready to navigate the open waters seamlessly.

Inspecting Your Rigging

Rigging a yacht is a meticulous process that demands careful attention to detail. One crucial aspect is inspecting your rigging. This step ensures the safety and efficiency of your sailing adventure. Regular inspections , even before you set sail, can identify potential issues and help prevent mishaps on the water . Inspecting your rigging is not only a safety measure but also a way to guarantee that your yacht performs at its best, allowing you to enjoy smooth and stress-free sailing experiences.

Rigging Replacement

When it comes to maintaining your yacht's rigging, the necessity of rigging replacement cannot be overstated. Whether due to wear and tear or a desire to upgrade to modern materials, knowing when and how to replace your rigging is crucial.

Specialized Rigs for Small Sailboats

For small sailboat enthusiasts , specialized rigs can enhance your sailing experience. Explore the options available for these nimble vessels.

Ship Rigging Terms

Sailboat rigging comes with its unique terminology. Get acquainted with the essential terms:

- Mast: The vertical spar or structure that supports sails and rigging.

- Boom: A horizontal spar that extends from the mast to support the bottom of a sail.

- Shroud: Rigging wires that support the mast from the sides.

- Stay: Rigging wires that support the mast from the front or back.

- Halyard: Lines used to raise and lower sails.

- Sheet: Lines used to control the angle of the sails with respect to the wind.

- Jib: A triangular foresail set in front of the mast.

- Tack: The lower forward corner of a sail.

- Clew: The lower after corner of a sail.

- Topping Lift: A line that supports the boom when the sail is not in use.

Understanding these ship rigging terms is essential for efficient and safe sailing, allowing you to communicate effectively with your crew and navigate the open waters with confidence.

Sailboat Stays and Shrouds

Sailboat rigging comprises various components, and among the most critical are sailboat stays and shrouds. Stays are the fixed support cables or wires that keep the mast upright, while shrouds add lateral support, preventing the mast from swaying. These components work together to maintain the mast's stability and ensure safe and efficient sailing. The proper tension and alignment of stays and shrouds are crucial for the overall performance and safety of a sailboat. Regular inspections and maintenance of these rigging elements are essential to prevent wear and tear, making sure they remain reliable on your sailing adventures. Understanding the role of sailboat stays and shrouds is fundamental for any sailor, whether you're navigating coastal waters or crossing the open sea.

In conclusion, boat rigging is a multifaceted subject that greatly influences your sailing experience. Understanding the fundamentals, material choices, and the process of rigging a yacht is essential for a successful voyage.

So what are you waiting for? Take a look at our range of charter boats and head to some of our favourite

sailing destinations .

Sail Rigs And Types - The Only Guide You Need

Last Updated by

Daniel Wade

June 15, 2022

A well-designed sailboat is a thing of pure beauty. Whether you're a proud owner of one, a guest on one, or a shore-side admirer, you'll fall in love with the gliding sails, the excitement of a race, and the eco-friendly nature of these sophisticated yet magnificent vessels. With good sails, great design, and regular maintenance, sails and rigs are an important part of a sailboat.

If you’re thinking about going sailing, one of the first things you have to understand is the variety of modern sail plans. Unlike old sailboats, modern sailboats don't need huge, overlapping headsails and multiple masts just to get moving. In the past, when sailboats were heavy, keels were long, the only way to get the boat moving was with a massive relative sail area. You needed as much square footage as you could just to get your sailboat moving. But with the invention of fiberglass hulls, aluminum or composite masts, high-tensile but low diameter lines and stats, and more efficient sails, sailboats no longer need to plan for such large sail plans.. Still, there are various rig styles, from the common sloop, to the comfortable cat-rig, to the dual masted ketch and schooner, there are various sail types and rigs to choose from. The most important thing is to know the different types of sails and rigs and how they can make your sailing even more enjoyable.

There are different types of sails and rigs. Most sailboats have one mainsail and one headsail. The mainsail is generally fore-and-aft rigged and is triangular shaped. Various conditions and courses require adjustments to the sails on the boats, and, other than the mainsail, most boats can switch out their secondary sail depending on various conditions.. Do you want to sail upwind or go downwind? You cannot hoist just any sail and use it. It's, therefore, of great importance to understand how and when to use each sail type.

In this in-depth article, we'll look at various sail types and rigs, and how to use them to make your sailing more enjoyable.

Table of contents

Different Sail Types

It is perhaps worth noting that a sailboat is only as good as its sails. The very heart of sailing comes in capturing the wind using artfully trimmed sails and turning that into motion. . Ask any good sailor and he'll tell you that knowing how and when to trim the sails efficiently will not only improve the overall performance of your boat but will elevate your sailing experience. In short, sails are the driving force of sailboats.

As such, it's only natural that you should know the different types of sails and how they work. Let's first highlight different sail types before going into the details.

- Jib - triangular staysail

- Spinnaker - huge balloon-shaped downwind sail for light airs

- Genoa - huge jib that overlaps the mainsail

- Gennaker - a combination of a spinnaker and genoa

- Code zero - reaching genoa for light air

- Windseeker - tall, narrow, high-clewed, and lightweight jib

- Drifter - versatile light air genoa made from particularly lightweight cloth

- Storm jib - a smaller jib meant for stormy conditions

- Trysail - This is a smaller front-and-aft sail for heavy weather

The mainsail is the principal sail on a boat. It's generally set aft of the mainmast. Working together with the jib, the mainsail is designed to create the lift that drives the sailboat windward. That being said, the mainsail is a very powerful component that must always be kept under control.

As the largest sail, and the geometric center of effort on the boat, the mainsail is tasked with capturing the bulk of the wind that's required to propel the sailboat. The foot, the term for the bottom of any sail, secures to the boom, which allows you to trim the sail to your heading. The luff, the leading edge of the sail, is attached to the mast. An idealized mainsail would be able to swing through trim range of 180°, the full semi-circle aft of the mast, though in reality, most larger boats don’t support this full range of motion, as a fully eased sail can occasionally be unstable in heavy breeze.

. As fully controlling the shape of the mainsail is crucial to sailing performance, there are many different basic mainsail configurations. For instance, you can get a full-batten mainsail, a regular mainsail with short battens, or a two-plus-two mainsail with two full-length battens. Hyper-high performance boats have even begun experimenting with winged sails which are essentially trimmable airplane wings! Moreover, there are numerous sail controls that change the shape by pulling at different points on the sail, boom, or mast. Reefing, for instance, allows you to shorten the sail vertically, reducing the amount of sail area when the boat is overpowered.

Features of a Mainsail

Several features will affect how a particular sail works and performs. Some features will, of course, affect the cost of the sail while others may affect its longevity. All in all, it's essential to decide the type of mainsail that's right for you and your sailing application.

Sail Battens, the Roach, and the Leech

The most difficult part of the sail to control, but also the most important, are the areas we refer to as the leech and the roach. The roach is the part of the sail that extends backwards past the shortest line between the clew, at the end of the boom, and the top of the mast. It makes up roughly the back third of the sail. The leech is the trailing edge of the sail, the backmost curve of the roach. Together, these two components control the flow of the air off the back of the sail, which greatly affects the overall sail performance. If the air stalls off the backside of the sail, you will find a great loss in performance. Many sail controls, including the boom vang, backstay, main halyard, and even the cunningham, to name a few, focus on keeping this curve perfect.

As for parts of the sail itself, battens control the overall horizontal shape of the sail. Battens are typically made from fiberglass or wood and are built into batten pockets. They're meant to offer support and tension to maintain the sail shape Depending on the sail technology you want to use, you may find that full battens, which extend from luff to leech, or short battens, just on the trailing edge, are the way to go. Fully battened sails tend to be more expensive, but also higher performance.

Fully Battened Mainsails

They're generally popular on racing multihulls as they give you a nice solid sail shape which is crucial at high speeds. In cruising sailboats , fully battened mainsails have a few benefits such as:

- They prevent the mainsail from ragging. This extends the life of the sail, and makes maneuvers and trimming easier for the crew.

- It provides shape and lift in light-air conditions where short-battened mainsails would collapse.

On the other hand, fully-battened mainsails are often heavier, made out of thicker material, and can chafe against the standing rigging with more force when sailing off the wind.

Short Battens

On the other hand, you can choose a mainsail design that relies mostly on short battens, towards the leech of the sail. This tends to work for lighter cloth sails, as the breeze, the headsail, and the rigging help to shape the sail simply by the tension of the rig and the flow of the wind. The battens on the leech help to preserve the shape of the sail in the crucial area where the air is flowing off the back of the sail, keeping you from stalling out the entire rig.

The only potential downside is that these short battens deal with a little bit of chafe and tension in their pockets, and the sail cloth around these areas ought to be reinforced. If your sails do not have sufficient reinforcement here, or you run into any issues related to batten chafe, a good sail maker should be able to help you extend the life of your sails for much less than the price of a new set.

How to Hoist the Mainsail

Here's how to hoist the mainsail, assuming that it relies on a slab reefing system and lazy jacks and doesn't have an in-mast or in-boom furling system.

- Maintain enough speed for steeragewhile heading up into the wind

- Slacken the mainsheet, boom vang, and cunningham

- Make sure that the lazy jacks do not catch the ends on the battens by pulling the lazy jacks forward.

- Ensure that the reefing runs are free to run and the proper reefs are set if necessary.

- Raise the halyard as far as you can depending on pre-set reefs.

- Tension the halyard to a point where a crease begins to form along the front edge

- Re-set the lazy jacks

- Trim the mainsail properly while heading off to your desired course

So what's Right for You?

Your mainsail will depend on how you like sailing your boat and what you expect in terms of convenience and performance. That being said, first consult the options that the boatbuilder or sailmakers suggest for your rig. When choosing among the various options, consider what you want from the sail, how you like to sail, and how much you're willing to spend on the mainsail.

The headsail is principally the front sail in a fore-and-aft rig. They're commonly triangular and are attached to or serve as the boat’s forestay. They include a jib and a genoa.

A jib is a triangular sail that is set ahead of the foremost sail. For large boats, the roto-furling jib has become a common and convenient way to rig and store the jib. Often working in shifts with spinnakers, jibs are the main type of headsails on modern sailboats. Jibs take advantage of Bournoulli’s Principle to break the incoming breeze for the mainsail, greatly increasing the speed and point of any boat. By breaking the incoming wind and channeling it through what we call the ‘slot,’ the horizontal gap between the leech of the jib and the luff of the mainsail, the jib drastically increases the efficiency of your mainsail. It additionally balances the helm on your rudder by pulling the bow down, as the mainsail tends to pull the stern down. .

The main aim of the jib is to increase the sail area for a given mast size. It improves the aerodynamics of the mainsails so that your sailboat can catch more wind and thereby sail faster, especially in light air

Using Jibs on Modern Sailboats

In the modern contexts, jib’s mainly serve increase the performance and overall stability of the mainsail. The jib can also reduce the turbulence of the mainsail on the leeward side.

On Traditional Vessels

Traditional vessels such as schooners have about three jibs. The topmast carried a jib topsail, the main foresail is called the jib, while the innermost jib is known as the staysail. The first two were employed almost exclusively by clipper ships.

How to Rig the Jibs

There are three basic ways to rig the jib.

Track Sheets - A relatively modern approach to the self-tacking jib, this entails placing all the trimming hardware on a sliding track forward of the mast. This means that on each tack, the hardware slides from one side of the boat to the other. This alleviates the need to switch sheets and preserves the trim angle on both sides, though it can be finnicky and introduce friction.

Sheet up the Mast - This is a very popular approach and for a good reason. Hoist the jib sheet up the mast high enough to ensure that there's the right tension through the tack. Whether internally or externally, the sheet returnsto the deck and then back to the cockpit just like the rest of the mast baselines. The fact the hardware doesn't move through the tacks is essential in reducing friction.

Sheet Forward - This method revolves around ensuring that the jib sheet stays under constant pressure so that it does not move through the blocks in the tacks. This is possible if the through-deck block is extremely close to the jib tack. Your only challenge will only be to return the sheet to the cockpit. This is, however, quite challenging and can cause significant friction.

Dual Sheeting - The traditional method, especially on smaller dinghies, though it is not self-tacking. This requires a two ended or two separate sheet system, where one sheet runs to a block on starboard, and the other to port. Whenever you tack or gybe, this means you have to switch which sheet is active and which is slack, which is ok for well crewed boats, but a potential issue on under-crewed boats.

Another important headsail, a genoa is essentially a large jib that usually overlaps the mainsail or extends past the mast, especially when viewed from the other side. In the past, a genoa was known as the overlapping jib and is technically used on twin-mast boats and single-mast sloops such as ketches and yawls. A genoa has a large surface area, which is integral in increasing the speed of the vessel both in moderate and light winds.

Genoas are generally characterized by the percentage they cover. In most cases, sail racing classes stipulate the limit of a genoa size. In other words, genoas are usually classified by coverage.

Top-quality genoa trim is of great importance, especially if the wind is forward of the beam. This is because the wind will first pass over the genoa before the mainsail. As such, a wrongly sheeted genoa can erroneously direct the wind over the mainsail,spelling doom to your sailing escapades. While you can perfectly adjust the shape of a genoa using the mast rake, halyard tension, sheet tension, genoa car positioning, and backstay tension, furling and unfurling a genoa can be very challenging, especially in higher winds.

That being said, here are the crucial steps to always keep in mind.

- Unload and ease the loaded genoa sheet by going to a broad reach

- Do not use the winch; just pull on the furling line

- Keep a very small amount of pressure or tension on the loaded genoa sheet

- Secure the furling line and tighten the genoa sheets

- Get on the proper point of sail

- Have the crew help you and release the lazy genoa sheets

- Maintain a small tension while easing out the furling line

- Pull-on a loaded genoa sheet

- Close or cleat off the rope clutch when the genoa is unfurled

- Trim the genoa

To this end, it's important to note that genoas are popular in some racing classes. This is because they only categorize genoas based on the fore-triangle area covered, which essentially allows a genoa to significantly increase the actual sail area. On the contrary, keep in mind that tacking a genoa is quite a bit harder than a jib, as the overlapping area can get tangled with the mast and shrouds. It's, therefore, important to make sure that the genoa is carefully tended, particularly when tacking.

Downwind Sails

Modern sailboats are a lot easier to maneuver thanks to the fore-and-aft rig. Unfortunately, when sailing downwind they catch less wind, and downwind sails are a great way of reducing this problem. They include the spinnaker and the gennaker.

A spinnaker will, without a doubt, increase your sailing enjoyment. But why are they often buried in the cabin of cruising boats? Well, the first few attempts to rig and set a spinnaker can be difficult without enough help and guidance. Provided a solid background, however, spinnakers are quite straightforward and easy to use and handle with teamwork and enough practice. More importantly, spinnakers can bring a light wind passage to life and can save your engine.

Spinnakers are purposely designed for sailing off the wind; they fill with wind and balloon out in front of your sailboat. Structured with a lightweight fabric such as nylon, the spinnaker is also known as a kite or chute, as they look like parachutes both in structure and appearance.

A perfectly designed spinnaker should have taut leading edges when filled. This mitigates the risk of lifting and collapsing. A spinnaker should have a smooth curve when filled and devoid of depressions and bubbles that might be caused by the inconsistent stretching of the fabric. The idea here is that anything other than a smooth curve may reduce the lift and thereby reduce performance.

Types of Spinnakers

There are two main types of spinnakers: symmetric spinnakers and asymmetric spinnakers.

Asymmetric Spinnakers

Flown from a spinnaker pole or bowsprit fitted to the bow of the boat, asymmetric spinnakers resemble large jibs and have been around since the 19th century. The concept of asymmetric spinnaker revolves around attaching the tack of the spinnaker at the bow and pulling it around during a gybe.

Asymmetric spinnakers have two sheets just like a jib., These sheets are attached at the clew and never interact directly with the spinnaker pole. This is because the other corner of the spinnaker is fixed to the bowsprit. The asymmetric spinnaker works when you pull in one sheet while releasing the other. This makes it a lot easier to gybe but is less suited to sailing directly downwind. There is the loophole of having the asymmetric spinnaker gybed to the side opposite of the boom, so that the boat is sailing ‘wing-on-wing,’ though this is a more advanced maneuver, generally reserved for certain conditions and tactical racing situations.

On the contrary, the asymmetric spinnaker is perfect for fast planing dinghies. This is because such vessels have speeds that generate apparent wind forward. Because asymmetrics, by nature, prefer to sail shallower downwind angles, this apparent wind at high speeds makes the boat think that it is sailing higher than it really is, allowing you to drive a little lower off the breeze than normal. . In essence, the asymmetric spinnaker is vital if you're looking for easy handling.

Symmetric Spinnakers

Symmetric spinnakers are a classic sail type that has been used for centuries for controlling boats by lines known as a guy and a sheet. The guy, which is a windward line, is attached to the tack of the sail and stabilized by a spinnaker pole. The sheet, which is the leeward line, is attached to the clew of the spinnaker and is essential in controlling the shape of the spinnaker sail.

When set correctly, the leading edges of the symmetric spinnaker should be almost parallel to the wind. This is to ensure that the airflow over the leading edge remains attached. Generally, the spinnaker pole should be at the right angles to the apparent wind and requires a lot of care when packing.

The main disadvantage of this rig is the need to gybe the spinnaker pole whenever you gybe the boat. This is a complicated maneuver, and is one of the most common places for spinnakers to rip or get twisted. If, however, you can master this maneuver, you can sail at almost any angle downwind!

How to Use Spinnaker Effectively

If you decide to include the spinnakers to your sailboat, the sailmaker will want to know the type of boat you have, what kind of sailing you do, and where you sail. As such, the spinnaker that you end up with should be an excellent and all-round sail and should perform effectively off the breeze

The type of boat and where you'll be sailing will hugely influence the weight of your spinnaker cloth. In most cases, cruising spinnakers should be very light, so if you've decided to buy a spinnaker, make sure that it's designed per the type of your sailboat and where you will be sailing. Again, you can choose to go for something lighter and easier to set if you'll be sailing alone or with kids who are too young to help.

Setting up Spinnakers

One of the main reasons why sailors distrust spinnakers is because they don't know how to set them up. That being said, a perfectly working spinnaker starts with how you set it up and this revolves around how you carefully pack it and properly hook it up. You can do this by running the luff tapes and ensuring that the sails are not twisted when packed into the bag. If you are using large spinnakers, the best thing to do is make sure that they're set in stops to prevent the spinnakers from filling up with air before you even hoist them fully.

But even with that, you cannot fully set the spinnaker while sailing upwind. Make sure to bear away and have your pole ready to go as you turn downwind. You should then bear away to a reach before hoisting. Just don't hoist the spinnakers from the bow as this can move the weight of the crew and equipment forward.

Used when sailing downwind, a gennaker is asymmetric sail somewhere between a genoa and a spinnaker. It sets itself apart because it gennaker is a free-flying asymmetric spinnaker but it is tacked to the bowsprit like the jib.

Let's put it into perspective. Even though the genoa is a great sail for racing and cruising, sailors realized that it was too small to be used in a race or for downwind sail and this is the main reason why the spinnaker was invented. While the spinnakers are large sails that can be used for downwind sail, they are quite difficult to handle especially if you're sailing shorthanded. As such, this is how a gennaker came to be: it gives you the best of both worlds.

Gennakers are stable and easy to fly and will add to your enjoyment and downwind performance.

The Shape of a Gennaker

As we've just noted, the gennaker is asymmetrical. It doesn't attach to the forestay like the genoa but has a permanent fitting from the mast to bow. It is rigged exactly like a spinnaker but its tack is fastened to the bowsprit. This is fundamentally an essential sail if you're looking for something to bridge the gap between a genoa and a spinnaker.

Setting a Gennaker

When cruising, the gennaker is set with the tack line from the bow, a halyard, and a sheet that's led to the aft quarter. Attach the tack to a furling unit and attach it to a fitting on the hull near the very front of the sailboat. You can then attach the halyard that will help in pulling it up to the top of the mast before attaching it to the clew. The halyard can then run back to the winches to make the controlling of the sail shape easier, just like when using the genoa sail.

In essence, a gennaker is a superb sail that will give you the maximum versatility of achieving the best of both a genoa and a spinnaker, especially when sailing downwind. This is particularly of great importance if you're cruising by autopilot or at night.

Light Air Sails

Even though downwind sails can be used as light air sails, not all light air sails can be used for downwind sailing. In other words, there's a level of difference between downwind sails and light air sails. Light air sails include code zero, windseeker, and drifter reacher.

A cross between an asymmetrical spinnaker and a genoa, a code zero is a highly modern sail type that's generally used when sailing close to the wind in light air. Although the initial idea of code zero was to make a larger genoa, it settled on a narrow and flat spinnaker while upholding the shape of a genoa.

Modern boats come with code zero sails that can be used as soon as the sailboat bears off close-hauled even a little bit. It has a nearly straight luff and is designed to be very flat for close reaching. This sail is designed to give your boat extra performance in light winds, especially in boats that do not have overlapping genoas. It also mitigates the problem of loss of power when you are reaching with a non-overlapping headsail. Really, it is closer to a light air jib that sacrifices a little angle for speed.

In many conditions, a code zero sail can go as high as a sailboat with just a jib. By hoisting a code zero, you'll initially have to foot off about 15 degrees to fill it and get the power that you require to heel and move the boat. The boat will not only speed up but will also allow you to put the bow up while also doing the same course as before you set the zero. In essence, code zero can be an efficient way of giving your boat about 30% more speed and this is exactly why it's a vital inventory item in racing sailboats.

When it comes to furling code zero, the best way to do it is through a top-down furling system as this will ensure that you never get a twist in the system.

Generally used when a full size and heavier sail doesn't stay stable or pressurized, a windseeker is a very light sail that's designed for drifting conditions. This is exactly why they're designed with a forgiving cloth to allow them to handle these challenging conditions.

The windseeker should be tacked at the headstay with two sheets on the clew. To help this sail fill in the doldrums, you can heel the boat to whatever the apparent leeward side is and let gravity help you maintain a good sail shape while reaching.The ideal angle of a windseeker should be about 60 degrees.

Though only used in very specific conditions, the windseeker is so good at this one job that it is worth the investment if you plan on a long cruise. Still, you can substitute most off the breeze sails for this in a pinch, with slightly less performance gain, likely with more sacrifices in angle to the breeze.

Drifter Reacher

Many cruising sailors often get intimidated by the idea of setting and trimming a drifter if it's attached to the rig at only three corners or if it's free-flying. But whether or not a drifter is appropriate for your boat will hugely depend on your boat's rig, as well as other specific details such as your crew's ability to furl and unfurl the drifter and, of course, your intended cruising grounds.

But even with that, the drifter remains a time-honored sail that's handy and very versatile. Unlike other light air sails, the drifter perfectly carries on all points of sails as it allows the boat to sail close-hauled and to tack. It is also very easy to control when it's set and struck. In simpler terms, a drifter is principally a genoa that's built of lightweight fabric such as nylon. Regardless of the material, the drifter is a superb sail if you want to sail off a lee shore without using the genoa.

Generally stronger than other regular sails, stormsails are designed to handle winds of over 45 knots and are great when sailing in stormy conditions. They include a storm jib and a trysail.

If you sail long and far enough, chances are you have or will soon be caught in stormy conditions. Under such conditions, storm jibs can be your insurance and you'll be better off if you have a storm jib that has the following features:

- Robustly constructed using heavyweight sailcloth

- Sized suitably for the boat

- Highly visible even in grey and white seas

That's not all; you should never go out there without a storm jib as this, together with the trysail, is the only sails that will be capable of weathering some of nature's most testing situations.

Storm jibs typically have high clews to give you the flexibility of sheet location. You can raise the sail with a spare halyard until its lead position is closed-hauled in the right position. In essence, storm jib is your insurance policy when out there sailing: you should always have it but always hope that you never have to use it.

Also known as a spencer, a trysail is a small, bright orange, veritably bullet-proof, and triangular sail that's designed to save the boat's mainsail from winds over 45 knots and works in the same way as a storm jib. It is designed to enable you to make progress to windward even in strong and stormy winds.

Trysails generally use the same mast track as the mainsail but you have to introduce the slides into the gate from the head of the trysail.

There are two main types of rigs: the fore-and-aft rig and the square rigg.

Fore-and-aft Rig

This is a sailing rig that chiefly has the sails set along the lines of the keel and not perpendicular to it. It can be divided into three categories: Bermuda rig, Gaff rig, and Lateen rig.

Bermuda Rig - Also known as a Marconi rig, this is the typical configuration of most modern sailboats. It has been used since the 17th century and remains one of the most efficient types of rigs. The rig revolves around setting a triangular sail aft of the mast with the head raised to the top of the mast. The luff should run down the mast and be attached to the entire length.

Gaff Rig - This is the most popular fore-and-aft rig on vessels such as the schooner and barquentine. It revolves around having the sail four-cornered and controlled at its peak. In other words, the head of the mainsail is guided by a gaff.

Lateen Rig - This is a triangular fore-and-aft rig whereby a triangular sail is configured on a long yard that's mounted at a given angle of the mast while running in a fore-and-aft direction. Lateen rig is commonly used in the Indian Ocean and the Mediterranean.

Square Rigged

This is a rig whereby the mainsails are arranged in a horizontal spar so that they're square or vertical to the mast and the keel of the boat. The square rig is highly efficient when sailing downwind and was once very popular with ocean-going sailboats.

Unquestionably, sailing is always pleasurable. Imagine turning off the engine of your boat, hoisting the sails, and filling them with air! This is, without a doubt, a priceless moment that will make your boat keel and jump forward!

But being propelled by the noiseless motion of the wind and against the mighty currents and pounding waves of the seas require that you know various sail types and how to use them not just in propelling your boat but also in ensuring that you enjoy sailing and stay safe. Sails are a gorgeous way of getting forward. They remain the main fascination of sailboats and sea cruising. If anything, sails and boats are inseparable and are your true friends when out there on the water. As such, getting to know different types of sails and how to use them properly is of great importance.

All in all, let's wish you calm seas, fine winds, and a sturdy mast!

Related Articles

I've personally had thousands of questions about sailing and sailboats over the years. As I learn and experience sailing, and the community, I share the answers that work and make sense to me, here on Life of Sailing.

by this author

Learn About Sailboats

Sailboat Parts

Most Recent

What Does "Sailing By The Lee" Mean?

October 3, 2023

The Best Sailing Schools And Programs: Reviews & Ratings

September 26, 2023

Important Legal Info

Lifeofsailing.com is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon. This site also participates in other affiliate programs and is compensated for referring traffic and business to these companies.

Similar Posts

Affordable Sailboats You Can Build at Home

September 13, 2023

Best Small Sailboat Ornaments

September 12, 2023

Discover the Magic of Hydrofoil Sailboats

December 11, 2023

Popular Posts

Best Liveaboard Catamaran Sailboats

December 28, 2023

Can a Novice Sail Around the World?

Elizabeth O'Malley

4 Best Electric Outboard Motors

How Long Did It Take The Vikings To Sail To England?

10 Best Sailboat Brands (And Why)

December 20, 2023

7 Best Places To Liveaboard A Sailboat

Get the best sailing content.

Top Rated Posts

Lifeofsailing.com is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon. This site also participates in other affiliate programs and is compensated for referring traffic and business to these companies. (866) 342-SAIL

© 2024 Life of Sailing Email: [email protected] Address: 11816 Inwood Rd #3024 Dallas, TX 75244 Disclaimer Privacy Policy

No products in the cart.

Sailing Ellidah is supported by our readers. Buying through our links may earn us an affiliate commission at no extra cost to you.

The Running Rigging On A Sailboat Explained

The running rigging on a sailboat consists of all the lines used to hoist, lower, and control the sails and sailing equipment. These lines usually have different colors and patterns to easily identify their function and location on the vessel.

Looking at the spaghetti of lines with different colors and patterns might get your head spinning. But don’t worry, it is actually pretty simple. Each line on a sailboat has a function, and you’ll often find labels describing them in the cockpit and on the mast.

In this guide, I’ll walk you through the functions of every component of the running rigging. We’ll also look at the hardware we use to operate it and get up to speed on some of the terminology.

The difference between standing rigging and running rigging

Sometimes things can get confusing as some of our nautical terms are used for multiple items depending on the context. Let me clarify just briefly:

The rig or rigging on a sailboat is a common term for two parts, the standing , and the running rigging.

- The standing rigging consists of wires supporting the mast on a sailboat and reinforcing the spars from the force of the sails when sailing. Check out my guide on standing rigging here!

- The running rigging consists of the halyards, sheets, and lines we use to hoist, lower, operate and control the sails on a sailboat which we will explore in this guide.

The components of the running rigging

Knowing the running rigging is an essential part of sailing, whether you are sailing a cruising boat or crewing on a large yacht. Different types of sailing vessels have different amounts of running rigging.

For example, a sloop rig has fewer lines than a ketch, which has multiple masts and requires a separate halyard, outhaul, and sheet for its mizzen sail. Similarly, a cutter rig needs another halyard and extra sheets for its additional headsail.

You can dive deeper and read more about Sloop rigs, Ketch Rigs, Cutter rigs, and many others here .

Take a look at this sailboat rigging diagram:

Lines are a type of rope with a smooth surface that works well on winches found on sailboats. They come in various styles and sizes and have different stretch capabilities.

Dyneema and other synthetic fibers have ultra-high tensile strength and low stretch. These high-performance lines last a long time, and I highly recommend them as a cruiser using them for my halyards.

A halyard is a line used to raise and lower the sail. It runs from the head of the sail to the masthead through a block and continues down to the deck. Running the halyard back to the cockpit is common, but many prefer to leave it on the mast.

Fun fact: Old traditional sailboats sometimes used a stainless steel wire attached to the head of the sail instead of a line!

Jib, Genoa, and Staysail Halyards

The halyard for the headsail is run through a block in front of the masthead. If your boat has a staysail, it needs a separate halyard. These lines are primarily untouched on vessels with a furling system except when you pack the sail away or back up. Commonly referred to as the jib halyard.

Spinnaker Halyard

A spinnaker halyard is basically the same as the main halyard but used to hoist and lower the spinnaker, gennaker, or parasailor.

The spinnaker halyard is also excellent for climbing up the front of the mast, hoisting the dinghy on deck, lifting the outboard, and many other things.

A sheet is a line you use to control and trim a sail to the angle of the wind . The mainsheet controls the angle of the mainsail and is attached between the boom and the mainsheet traveler . The two headsail sheets are connected to the sail’s clew (lower aft corner) and run back to each side of the cockpit.

These are control lines used to adjust the angle and tension of the sail. It is also the line used to unfurl a headsail on a furling system. Depending on what sail you are referring to, this can be the Genoa sheet , the Jib sheet , the Gennaker sheet , etc.

The outhaul is a line attached to the clew of the mainsail and used to adjust the foot tension. It works runs from the mainsail clew to the end of the boom and back to the mast. In many cases, back to the cockpit. On a boat with in-mast furling , this is the line you use to pull the sail out of the mast.

Topping lift

The topping lift is a line attached to the boom’s end and runs through the masthead and down to the deck or cockpit. It lifts and holds the boom and functions well as a spare main halyard. Some types of sailboat rigging don’t use a topping lift for their boom but a boom vang instead. Others have both!

Topping lifts can also be used to lift other spars.

A downhaul is a line used to lower with and typically used to haul the mainsail down when reefing and lowering the spinnaker and whisker poles. The downhaul can also control the tack of an asymmetrical spinnaker, gennaker, or parasailor.

Tweaker and Barber Haul

A tweaker is a line, often elastic, attached to the sheet of a headsail and used to fine-tune the tension on the sheet.

Barber haul

A barber haul is a line attached to a headsail’s sheet to adjust the sheeting angle to the wind. It is often used to pull the clew further toward the center or outboard than the cars allow.

Boom Preventer

A boom preventer is a line attached to the boom’s end when sailing off the wind. Its function is to hold the spar in place and prevent it from swinging wildly.

If the boat were to get an accidental gybe, it could cause serious damage to the rigging or even harm people on board. It is important for the rigger to be cautious when setting up the boom preventer.

Running Backstay

Running backstays is similar to a normal backstay but uses a line instead of a hydraulic tensioner. Some rigs have additional check stays or runners as well.

Bonus tip: Reefing

The term reefing is used when reducing the effective sailing area exposed to the wind of a given sail. Headsails are usually reefed by partially furling them in, and they often have marks for what we refer to as 1st, 2nd, and 3rd reefs.

The mainsail is reefed similarly with an in-mast furling or in-boom furling system.

On a traditional mast, we use a system called slab reefing. The system has reefing lines running through the boom to reinforced points on the luff and leech, allowing you to pull the sail down to the boom and effectively reduce the sail area.

Having at least two reefing points in the mainsail is normal, but most cruising sailboats have 3. The 3rd is used for the heaviest conditions, giving you only a tiny bit of sail area exposed to the wind.

You want to reef your sails before the wind increases to a point where your boat gets overpowered.

It is essential to practice your reefing technique . You will find yourself in situations with rapidly increasing winds where you need to reduce your sails quickly.

Rule of thumb: If you think setting a reef might be a good idea, do it.

Shaking a reef is the term used when we sail with a reefed sail and want to increase the sail area back to full.

Hardware used for sail handling and the running rigging

Furling system.

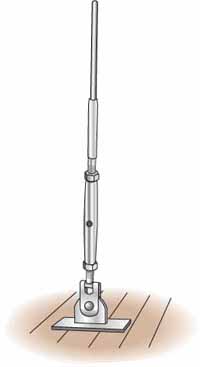

Most sailboats have their headsail on a furling system. A furling system is a tube that runs along the forestay from the bottom furler drum to the masthead swivel.

This system allows you to roll the headsail around the forestay, making furling the sail in and out accessible. It is also convenient when reefing the sail when the wind picks up, as you can easily do this from the safety of the cockpit. These furling systems come in manual versions and electric versions.

In-mast furling

In-mast furling is a system that rolls the mainsail in and out of the mast. To unfurl the mainsail, we use the outhaul .

In-boom furling

In-boom furling is a system that rolls the mainsail in and out of the boom. This system has been costly and has mostly been seen on big yachts earlier. They are becoming more affordable and common on smaller boats, though. To unfurl this setup, we use the main halyard.

A Stack pack is also called a Lazy Bag or Lazy Pack. It is a bag with a zip attached to the boom where the mainsail is stored when unused. It protects the mainsail from UV rays from the sun and weather elements. It is a very nice and tidy way to store the mainsail and reefing lines if you don’t have in-mast or in-boom furling.

Lazy Jacks is a system of lines running from the stack pack to the mast. The Lazy Jacks guide the mainsail up and down from the Stack Pack and prevent it from falling down on the deck. It is also possible to rig Lazy Jacks without a Stack Pack.

A block is a pulley with a sheave wheel. Blocks are used to change the direction of a pull on a line or rope and give a mechanical advantage. They have many uses, especially onboard sailboats.

A winch is a metal drum that gives you a mechanical advantage to control and tighten lines. These can be operated by turning a rope around it and pulling manually or by a winch handle to get more force. Most modern winches are self-tailing, which means they lock the line on so you can winch the line without holding on to it. Some boats even have electrical winches operated by a button.

Mainsheet Traveler

The mainsheet traveler is a horizontal track that the mainsheet is attached to through a series of blocks. The traveler enables you to adjust and lock the boom at an angle and also plays a critical part in trimming the mainsail.

Most cruising sailboats have their traveler attached to the top of the coachroof in front of the spray hood. A racing boat typically has the traveler in the cockpit near the helm to give the helmsman better control over the mainsheet.