The Use of the Sail in Ancient Mesopotamia

Why Was Egypt of Strategic Importance During WWII?

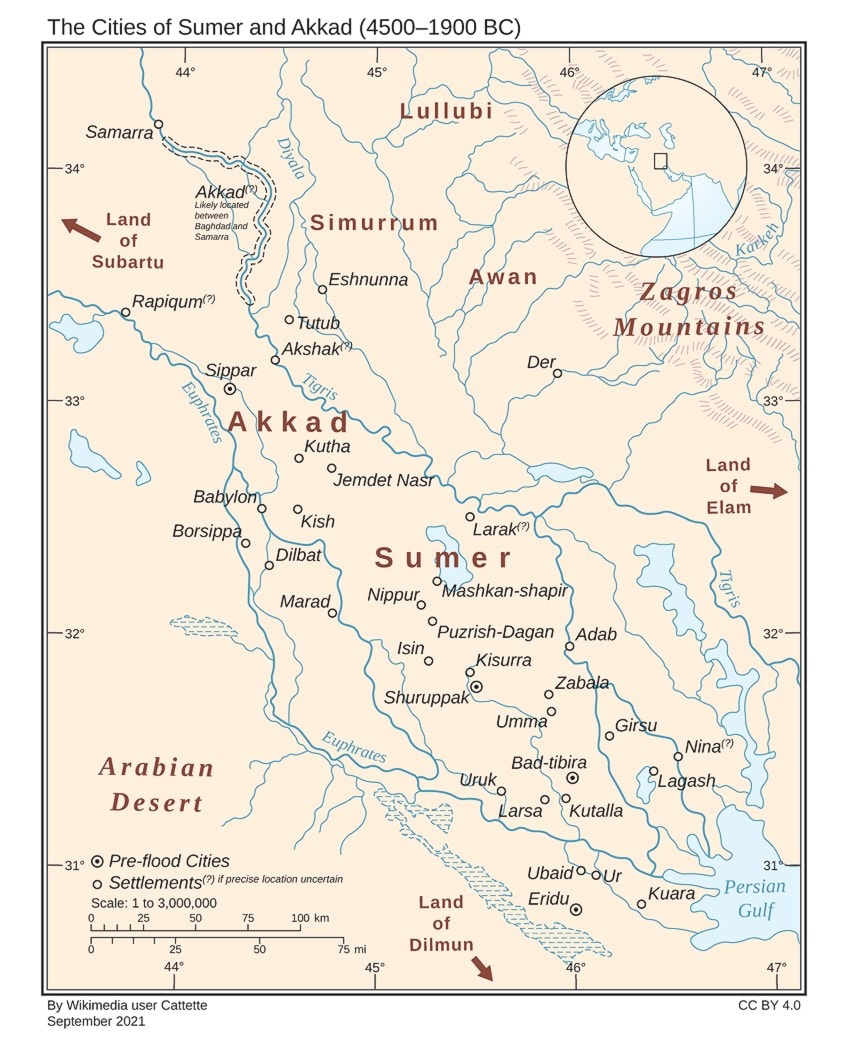

Mesopotamia was one of the earliest civilizations on the planet. Its name means "land between two rivers." The rivers described in the nation's title are the Tigris and the Euphrates. Mesopotamian citizens and their culture contributed immeasurably to life in the modern world. One of the most critical inventions in human history can be traced back to Mesopotamia: the invention of the sail.

The Mesopotamian Sailboat

Mesopotamia, tucked beneath the Tigris and the Euphrates rivers and home to the community of Sumer, was one of the earliest civilizations on the planet, but there were other civilizations nearby. As a land with precious little in the way of natural resources, Mesopotamians were beholden to other civilizations. In order to survive, Mesopotamians needed to trade and enter into commercial relationships with other societies.

In order to be able to trade, Mesopotamians needed to be able to travel. This was a more difficult prospect than is possibly conceivable to the modern imagination. Because of the location of the civilization being situated between two rivers, traveling to other communities by water was a necessity. Besides the fact that they were situated in an area surrounded by water, roads had not yet been developed, which made travel throughout the land mass a challenging and often dangerous enterprise. This is to say nothing of the risk Mesopotamians' wares faced, traveling in inhospitable climates over rough terrain. Water travel development was inevitable.

In addition to bringing people across the water to trade, the Mesopotamians also needed to be able to shuttle goods and wares – both goods they planned to sell and the goods they acquired upon their return. The development of the earliest boats meant that Mesopotamians could load up a water-faring vessel with goods and ride with them downstream toward the desired landing and trading place. However, people were required to steer, to row and to guide the boat. This made the earliest canoe-like structures difficult to use to transport goods.

The very first sailboats produced by the Mesopotamians would look extremely primitive by today's standards. The boats themselves were made of bundles of wood and a material called papyrus. The sails were made of linen or papyrus and were shaped like a large rectangle or a square. These simple boats could carry people and goods upstream and downstream and could be used to navigate difficult waterways or inclement weather. The addition of the sailboat to the Mesopotamian lifestyle changed everything about civilization as we know it.

What Did Mesopotamia Trade?

Trade was a key force in the development of the Mesopotamian civilization. Sumer, another name for the area where Mesopotamia was located (which today is known as Iraq or Kuwait), was a thriving civilization with art, music and writing. Because Mesopotamia was scarce in terms of natural resources necessary for survival, the Mesopotamians had to trade what they had or what they could make from what they had.

Mesopotamians typically traded wool, cloth and various kinds of jewels as well as staples like oil and wine. The jewels they traded were like lapis lazuli, and the wool they traded was from sheep or goats. Textiles, ivory, copper, reeds and other materials that could be used for building, decoration or entertainment were traded and sold in order to buy the kinds of natural resources that the Sumerians needed for agriculture, building and dwelling.

The trade routes along the Tigris and the Euphrates were among the most extensive and important trade routes in ancient history. The Mesopotamian economy was wholly reliant on the trade routes with which it was involved and required the constant commerce in which it engaged with other nearby cities in order to ensure its own survival.

Consequences of the Sumerian Sailboat Invention

The Sumerians had invented sailboats in order to more efficiently trade with neighboring civilizations. However, after navigating the waterways successfully with the sailboat, the Sumerians realized that it would be useful in wartime too.

The Sumerian sailboat was constructed from light materials which not only enabled it to float but allowed the boats to easily be ferried from land to sea and back again. As the Sumerian sailboats became increasingly used for battle or tactical maneuvering, the design of the boat evolved. Rather than a canoe-shaped vessel, the sides of the boat were raised up higher to protect the oarsmen and passengers from any planned sort of attack. The platforms inside of the ship were raised at an angle so that all of the men onboard would have the ability to fire at their enemy with good aim.

In later years, the Sumerians began to add large battering rams to the front of their ships so that they could deliberately smash into their opponent's boat during a battle. Because the sailing technology was dependent on wind rather than mechanized technology, the boats were still nowhere near as advanced as warships would become, but regardless, the development of the sailboat was a tremendous step forward in military tactics and planning. The impact of the development of the sailboat is still felt today.

What Did the Sumerians Invent?

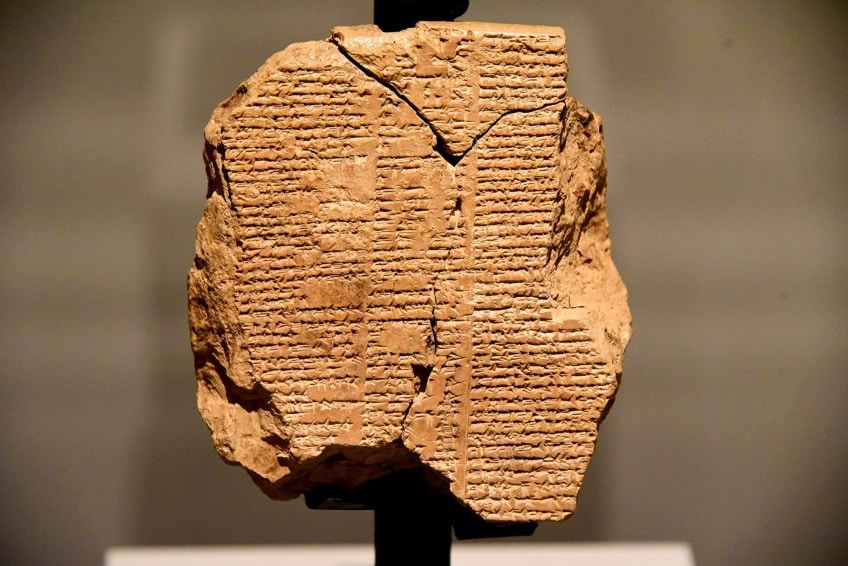

There are many things aside from the sailboat for which modern civilization is indebted to the Sumerians. If you look back at the history of Sumerian civilization and its innovations, it is striking to see how many pieces of our daily lives in the modern world are traceable back to the ancient civilization between the Tigris and the Euphrates. One of the most profound and world-changing innovations to come out of Sumerian society was the development of cuneiform. Cuneiform was an early form of writing that allowed Sumerians to keep track of their trading, their inventory and their crops. The Sumerians were meticulous bookkeepers, and their cuneiform is the basis for all written language.

Almost more critical than writing is the concept of time, an idea that can be traced back to the ancient Sumerians. Sumerians recognized the light in the sky and the subsequent darkness as the effect of a change. It was this innovative civilization that began to divide the day into portions based on a 60-second minute and then a 60-minute hour. In this realm of abstract concepts, we can also give credit to the Sumerians for the discovery of geometry and for developing a system of numbers and counting.

On the more practical side of things, Sumerians were responsible for innovating the very first wheeled vehicle. They developed schools and with them the concept of truancy and delinquency. They developed children's toys and writing implements and a variety of instruments and artistic tools that were designed to provoke pleasure and delight. The Sumerian inventions communicate that theirs was not a society founded simply on a need and desire for survival but one that also prized the arts, entertainment, child development and the pursuit of pleasure.

In terms of the advancements that help to build a society on a logistical level, we have the Sumerians to thank for much of that too. Domestication of animals, development of agricultural strategies and methods, the beginnings of irrigation plans, city building and improvements made to rudimentary dwelling structures all took place during the Sumerian civilization. Many dental and medical advancements were realized during this period as well.

Related Articles

Economic & Cultural Facts on the Neolithic Revolution

Things Sold & Traded in Ancient Greece

Purposes of Windmills in the 1800s

The Importance of Gunpowder as an Invention

The Importance of Farming to the Economy in Ancient Ghana

Commonly used household items in the 1960s.

How Pueblos Were Built

Why Was the Fertile Crescent a Major Means of Migration in Ancient ...

- Ancient History Encyclopedia: Sumerian Civilization: Inventing the Future

- Bright Hub Engineering: Ancient Mesopotamia Sailboats: An Introduction

- Khan Academy: The Sumerians and Mesopotamia

Ashley Friedman is a freelance writer with experience writing about education for a variety of organizations and educational institutions as well as online media sites. She has written for Pearson Education, The University of Miami, The New York City Teaching Fellows, New Visions for Public Schools, and a number of independent secondary schools. She lives in Los Angeles.

Sumerian Art – The Pottery, Carvings, and Architecture of Sumer Art

Considered the cradle of Civilization, ancient Mesopotamia was home to Sumer, located in the southern parts and one of its earliest and advanced civilizations during the Neolithic and early Bronze age. This article will explore the Sumerian culture and their artwork, ranging from pottery, statues, and architecture.

Table of Contents

- 1.1.1 The Importance of Uruk

- 2.1 Ram in a Thicket (c. 2 600 BC to 2 400 BC)

- 2.2 Standard of Ur (c. 2 600 BC to 2 400 BC)

- 2.3 The Queen’s Lyre (c. 2 600 BC)

- 2.4 Warka (Uruk) Vase (c. 3 200 BC – 3 000 BC)

- 3 Sumerian Architecture

- 4 From Writing to Wheels: The Sumerians Remembered

- 5.1 When Was the Sumerian Period?

- 5.2 What Does “Sumer” Mean?

- 5.3 What Kind of Art Was Created in Sumer?

- 5.4 What Was the Purpose of Sumerian Art?

Brief Historical Overview: “The Land Between the Rivers”

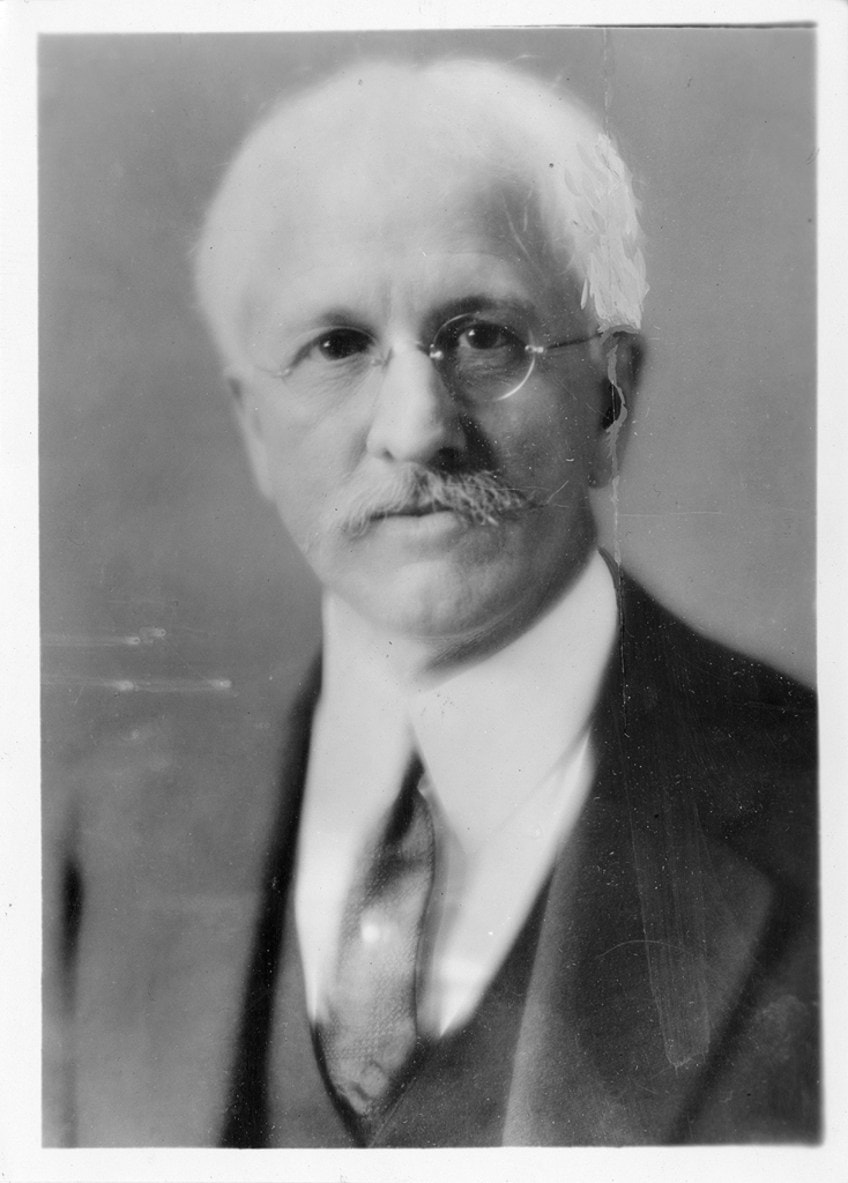

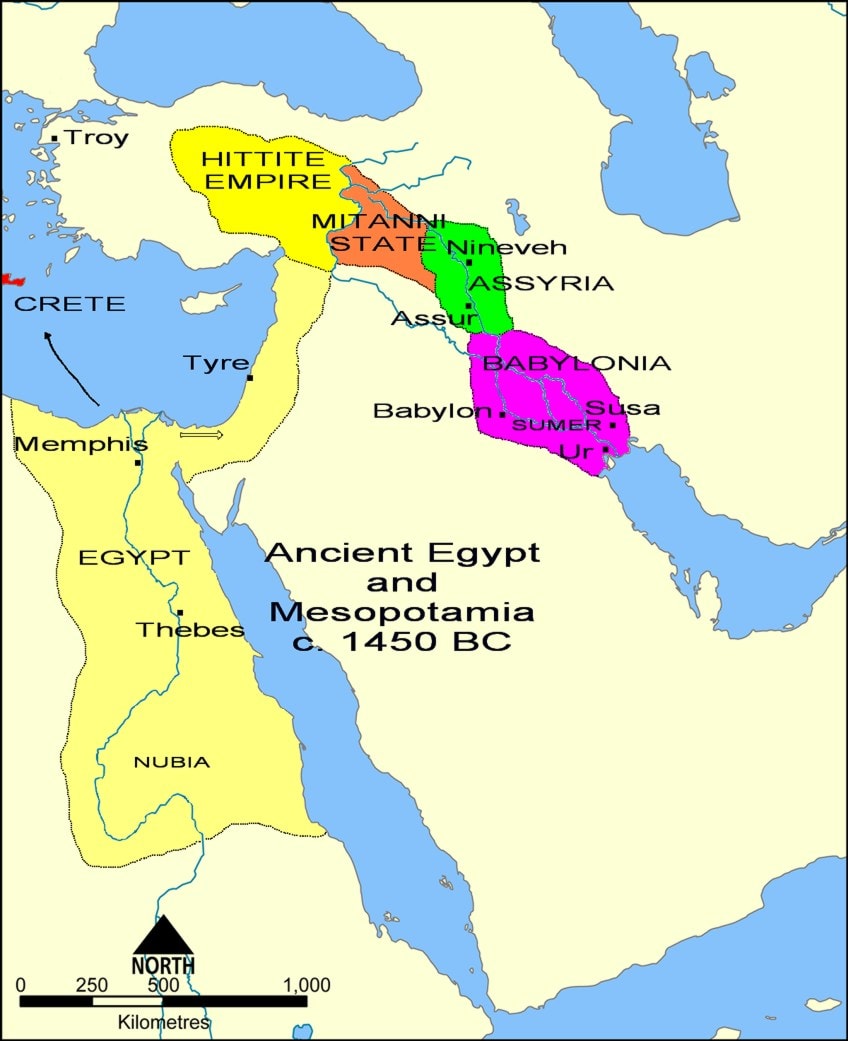

The Fertile Crescent can be found in the Near Middle East. It is also considered a Cradle of Civilization because of the rate of evolution of farming settlements, domestication, and other technological and cultural advancements like the wheel and writing. The name was introduced as the “Fertile Crescent” by the archaeologist James Henry Breasted in the publications Outlines of History (1914) and Ancient Times, A History of the Early World (1916). He described this region of the Middle East as follows:

“This fertile crescent is approximately a semi-circle, with the open side toward the south, having the west end at the southeast corner of the Mediterranean, the center directly north of Arabia, and the east end at the north end of the Persian Gulf”.

Other sources describe it as a “boomerang” shape, with the various regions surrounding it. These regions include areas of present-day Cyprus, Egypt, Iran, Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, Palestine, Syria, and Turkey.

As the name suggests, it was a fertile region with arable land and fresh water sources. Its vast biodiversity made it fit for farming and agriculture thousands of years ago when hunter-gatherers gradually transitioned to a more settled way of life. It is also located between North Africa and Eurasia and has been described as a “bridge” between these two regions.

It is no wonder then that the Fertile Crescent has been regarded as a Cradle of Civilization – it has been the birthplace of development and advancements of not only human civilization but also biodiversity.

If we zoom in to some of the first human civilizations that started here, we will find ancient Mesopotamia , which is now in the region of present-day Iraq, and other regions like Iran, Syria, Turkey, and Kuwait. Mesopotamia lies between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers and the name means the “land between the rivers”. It is one of four other river valley civilizations, the others being the Indus Valley Civilization, the Nile Valley in ancient Egypt , the Yellow River in ancient China.

Some historical scholars also suggest that the Agricultural, otherwise Neolithic, Revolution originated in ancient Mesopotamia. The dates suggested it started around 10 000 BC. Some of the earliest farming settlements or villages discovered date to around 11 500 BC to 7 000 BC. The archaeological site Tell Abu Hureyra is one example of this.

The people from Abu Hureyra are believed to have been hunter-gatherers who progressed to farming. Grinding tools were also excavated from this area, which suggests the inhabitants had access to grains, possibly the harvest of wild grains as it has been suggested.

It has also been discovered that early inhabitants domesticated animals like pigs and sheep also around the time of 11 000 to 9 000 BC, and farmed plants such as barley, flax, lentils, and wheat, dating to around 9 500 BC.

The Mesopotamian cultures were considered advanced in their developments – they created aqueducts, irrigation systems, astronomy, philosophy, the earliest forms of writing, and much more. It was one of the most complex regions in the world because of the diversity of cultures that moved through it.

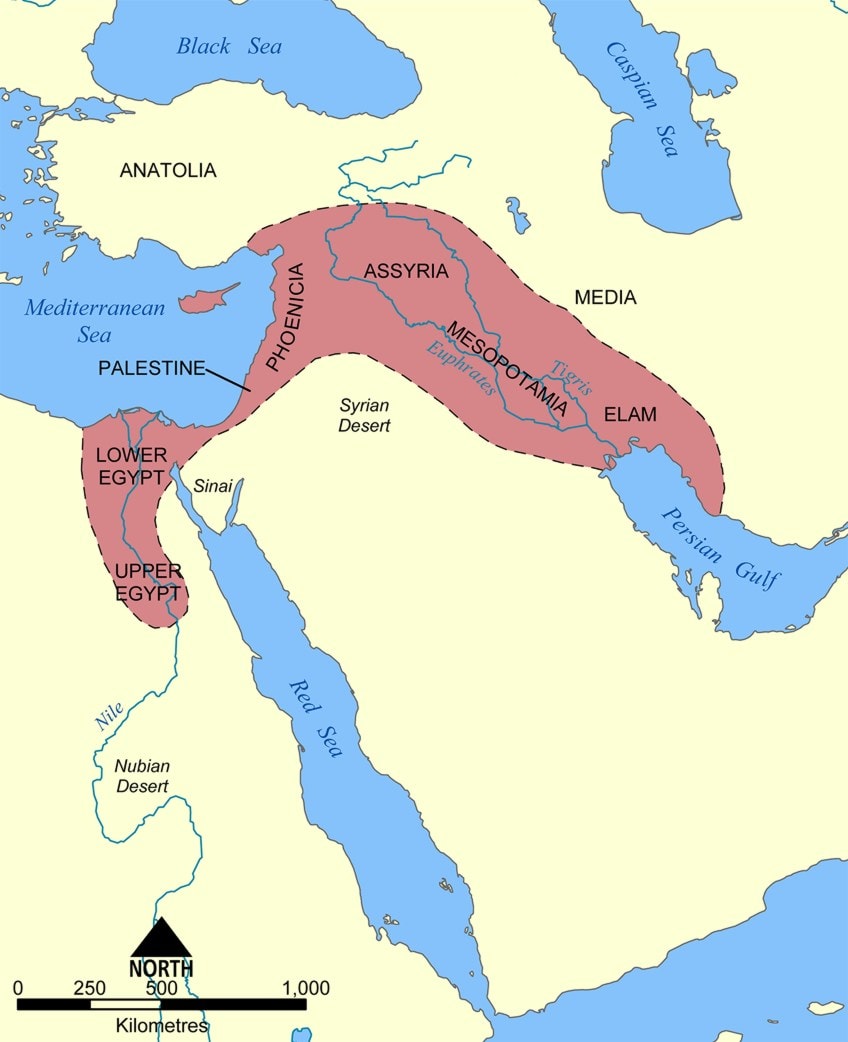

Some of the important civilizations from ancient Mesopotamia include Sumerians, Akkadians, Assyrians, and Babylonians. While there were many city-states throughout Mesopotamia, some of the important cities included the Sumerian Uruk, Ur, and Nippur. There was also Akkad, which was the capital city of the Akkadian Empire, the Assyrian cities Nineveh and Assur, and Babylon, the capital city of the Babylonian Empire.

Earliest Ancient Civilizations: Sumer

Sumer was one of the earliest Mesopotamian civilizations, which originated before the Akkadians, mentioned above. Sumer is in the southern part of Mesopotamia and is believed to have been settled around 4 500 BC to 4 000 BC.

The name “Sumer” was given to the Sumerians by the Akkadians, ironically.

“Black-headed people” or “Black-headed ones” is what the Sumerians used as their name for themselves. The Akkadians also used this terminology for the Sumerians. The word Kengir , meaning “Country of the Noble Lords” was the name the Sumerians used for their land.

There is a lot of scholarly debate about who the first people were to settle in Sumer; some suggest West Asian and others North African. It is generally believed that the first populations or settlements in Sumer were the Ubaidians or “proto-Euphrateans”.

According to various sources, the Ubaidians started agriculture by draining the surrounding marshes, they also developed trading systems and various crafts like weaving, metalwork, leatherwork, pottery, and masonry. The first and oldest settlement was believed to be Eridu, located southwest of the city called Ur.

Eridu was reportedly among five of the cities that were ruled by either a king or a “priestly governor” before floods were destroyed. The settlements were built around respective temples that venerated a patron god or goddess.

The Sumerian god, Enki, was also believed to have originated from Eridu at a place called Abzu, the waters or ocean, otherwise aquifers, under the earth; he was the god of water. Enki’s temple, otherwise referred to as the “House of the Aquifer”, was in the center of Eridu. The other pre-flood Sumerian cities include Bad-tibira, Larak, Sippar, and Shuruppak.

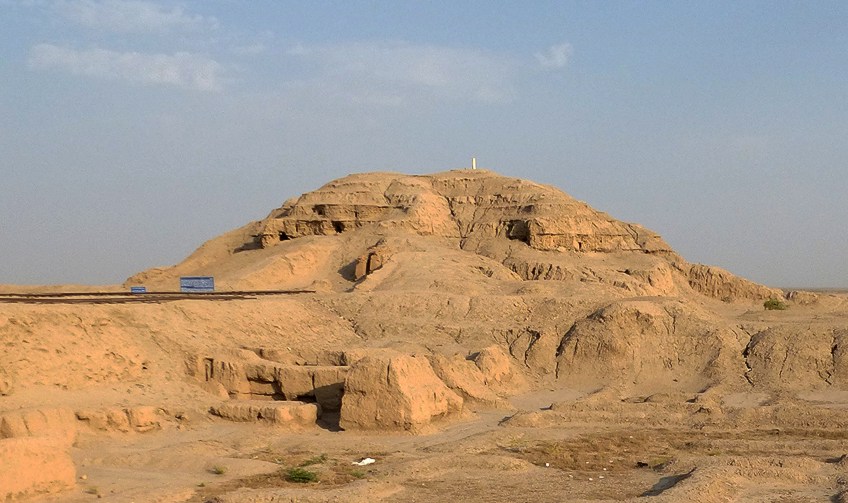

The Importance of Uruk

Uruk was considered one of the first “real” city-states when Sumerian civilization became more urbanized. It started around 4 000 BC and lasted until around 3 200 BC. There were various state formations like societal stratifications, military, and administration systems. It was divided into the Early Uruk Period (c. 4 000 BC to 3 500 BC) and the Late Uruk Period (3 500 BC to 3 100 BC).

It was one of the largest city-states in southern Mesopotamia with around 40,000 inhabitants and an estimation of around 80,000 to 90,000 people in the surrounding areas. It is believed to have reached its peak around 2 800 BC.

The Sumerian King List reportedly indicates that Uruk had five dynasties. It is worth noting that the fifth ruler (of the first dynasty) was the famous Gilgamesh who ruled around 2 900 BC to 2 700 BC. He was also the subject of the epic poem called the Epic of Gilgamesh (c. 2 100 BC to 1 200 BC).

Uruk is an important Sumerian city to note because of its advancements in urbanization as we will see from the wide range of the Sumerians’ architecture. Included were cultural advancements like writing, which is now known as the cuneiform script. It was initially used to record business transactions. These transactions were for purposes of keeping records of food and cattle. It was used by the ruling priests of the area.

The cuneiform script was made by pressing down a cut edge from a reed onto a clay tablet that was still soft. This created a shape that appeared like a wedge. The name also originates from the Latin meaning “wedge-shaped”.

This written language became a very flexible one because it could convey not only words but also numbers and concepts.

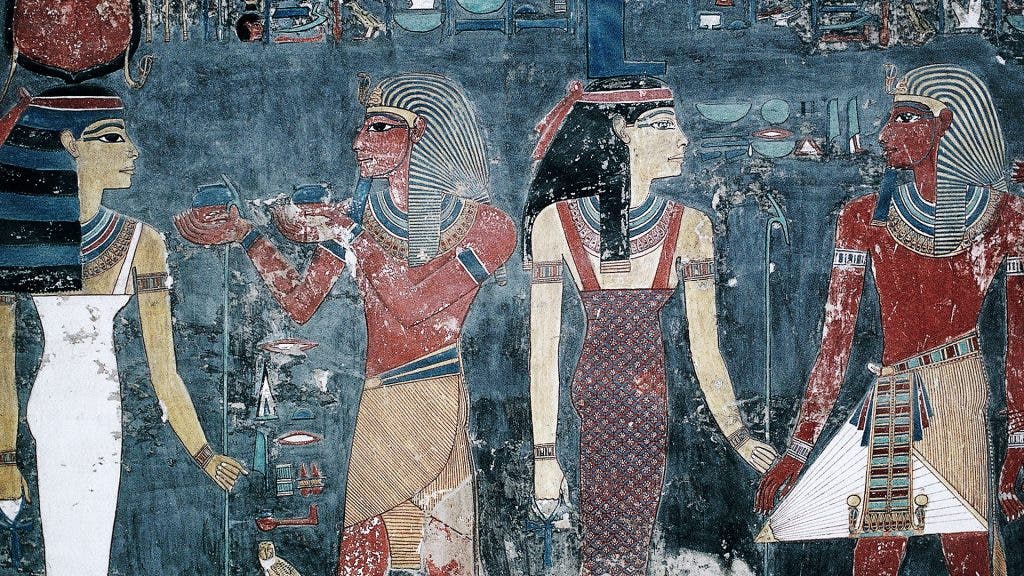

Sumerian Art

The Sumerian civilization was not only advanced in agriculture, economics, and many other facets of life, but they were also artists and builders. Their artworks served different purposes and functions and the addition of decorative elements gave any object a new character.

We will see this in the numerous Sumerian statues throughout the different dynasties. For example, the Standing Male Worshipper (c. 2 900 BC to 2 600 BC), now housed in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, depicting a man standing with both his hands cupped in front of his breastbone with a lustrous long beard and open eyes gazing outward; his facial features have been sculpted in an animated manner.

Not only were the Sumerians skilled at pottery and sculpture, but they produced beautiful pieces with these decorative elements made from semi-precious stones like alabaster, lapis lazuli, and serpentine to name a few. Some of these stones were also imported. They used metals like silver, gold, bronze, and copper as inlays and designs on various objects.

The Sumerians also used stone and clay. Clay was a popular medium to work with, possibly due to the clay present from the soil, and we will see a lot of Sumer art made from it. Decorative elements would adorn various items like jewelry, carved heads, musical instruments, ornamentation, weapons, cylinder seals, and many others.

The majority of Sumer art originates from gravesites; indeed, many objects, often important objects, were buried with the dead.

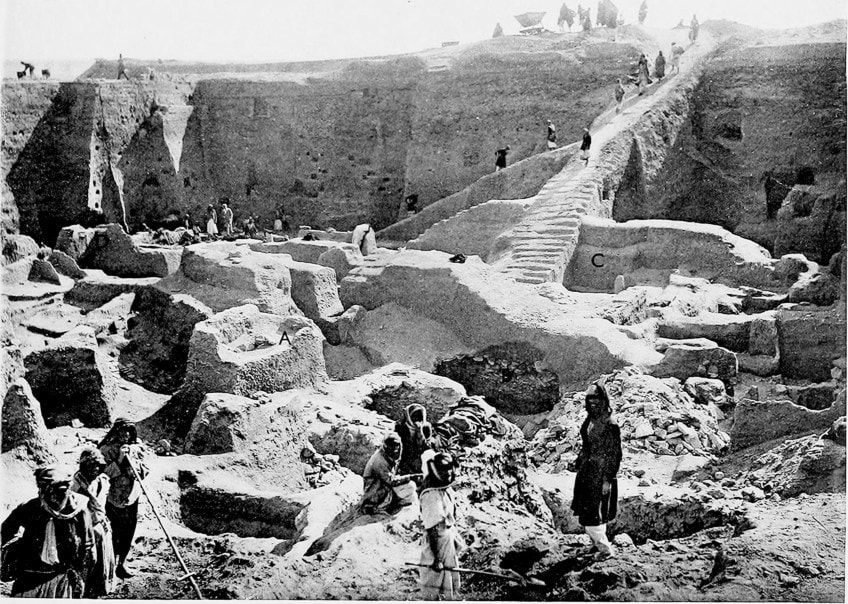

This also tells us that art served strong religious purposes during this period. One of the most important archaeological discoveries in history has been that of Sir Leonard Woolley, his wife Katharine Woolley, and their collaboration with the British Museum and the Museum of University of Pennsylvania.

From 1922 to 1934, Woolley, who was a British archaeologist, led an excavation at one of the Sumerian cities called Ur. The layout of the city consisted of central mud-brick temples with a surrounding cemetery. This is also where they discovered the Royal Cemetery, which was reportedly in an area used as a large rubbish heap where people could not build.

Instead, it was utilized as a burial site with various tombs that are believed to have belonged to Sumerian royalties.

The cemetery was dated from around 2 600 BC to 2 000 BC and the discovery of 16 graves dates these to around the middle of 3 000 BC. The tombs were also different in arrangement and size. The excavation team reportedly found over 2000 burials.

The tombs housed a plethora of objects like pottery including bowls, jars, and vases, jewelry, cylinder seals with inscriptions of the names of those who were dead, musical instruments of which lyres were quite prominent, sculptures, Sumer paintings, and many others.

One of the famous burial sites belonged to a woman, believed to be a “queen”, called Puabi.

She lived in the First Dynasty of Ur, around 2 600 BC. She was referred to as nin from the discovered cylinder seals. Nin is a Sumerian word that was used to refer to someone who was designated as a queen or priestess. It has also been translated to mean “lady”.

Her burial grave included numerous items that were tied to wealth, these were also high in quality items like jewelry, headdresses, including her own headdress with gold floral motifs and beads made from lapis lazuli and carnelian.

Sources also state these gravesites were looted over the years except for Puabi’s grave, which undoubtedly elicited questions about her status and importance in the Sumerian society.

It is important to remember there are hundreds of discovered Sumerian artifacts, all from different regions and all with different purposes and stories. Below we will discuss only a few of the famous pieces of Sumerian art, including, but not limited to some of the items discovered from the Royal Graves, including that of Puabi’s grave. It is encouraged to undertake more extensive research to discover all the other unique and beautiful Sumerian art pieces that adorn our museums in the present day.

Ram in a Thicket (c. 2 600 BC to 2 400 BC)

The Ram in a Thicket (c. 2 600 BC to 2 400 BC) is a figurine of a ram, really a goat, standing on its hind legs in front of what looks like a tree, possibly reaching for some food. This figurine came in a pair; the two were excavated from what was called the “Great Death Pit” in the Royal Cemetery at Ur, lying not too far apart from each other.

The British excavator, Leonard Woolley chose the name, Ram in a Thicket , because it resembled a reference from the book of Genesis, 22:13, in the Bible when Abraham was about to sacrifice Isaac, his son:

“Then Abraham looked up and saw a ram caught by its horns in a thicket. So he took the ram and sacrificed it as a burnt offering in place of his son”.

The figure measures 45.7 x 30.48 centimeters and is composed of silver, gold, lapis lazuli, shell, copper alloy, red limestone, and bitumen. An interesting fact about bitumen (or asphalt) is that the Sumerians used it as an adhesive. The Sumerian word for bitumen is believed to be esir .

If we look more closely at the Ram in a Thicket, we will notice it has a wooden core. The head and legs are covered in gold leaf that is attached to the wood; the adhesive qualities of bitumen keep it pasted on. The ears are made from copper. The horns are made from lapis lazuli.

From the dorsal view of the ram, there is what appears to be a fleece covering its upper shoulder area, which is also made from lapis lazuli; the fleece that covers the rest of its body is made from shell, also stuck on using bitumen. The ventral view shows the ram’s stomach area is made from a silver plate, but this is reportedly oxidized and unrepairable. The ram’s genitals are made from gold.

The tree itself is golden in color, made from gold leaf with gold flowers at the end of each branch. Both the ram and tree are on a small rectangular platform made from shell, lapis lazuli, and red limestone. It appears like a mosaic pattern covering the base. There is also a small tube protruding from each ram’s upper shoulder area, believed to have possibly been for supporting an object like a bowl.

Currently, the rams are in two different museums, one is in the British Museum’s Mesopotamia Gallery in London. The other ram is in the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology.

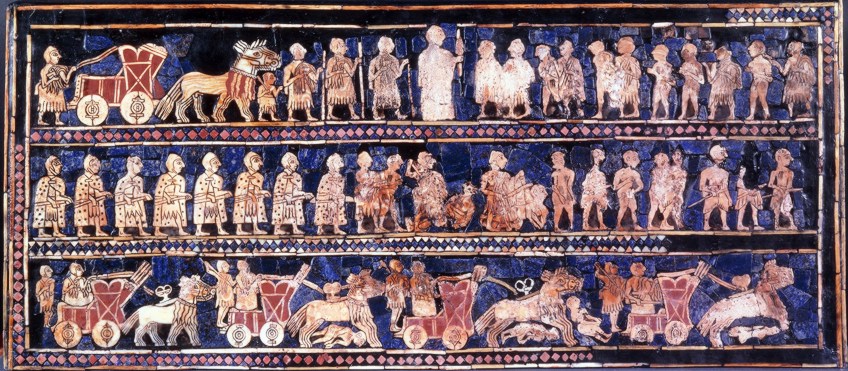

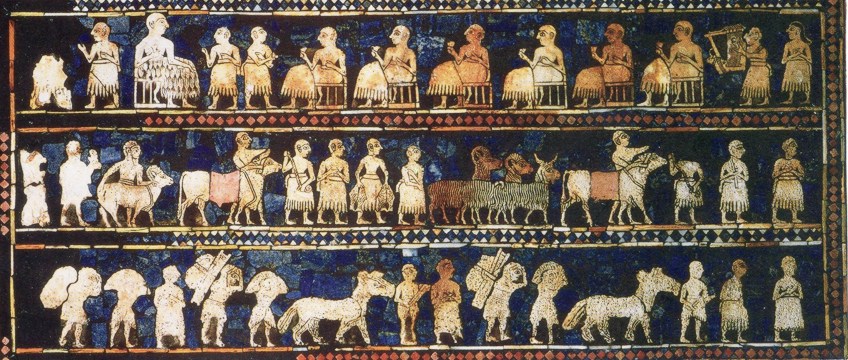

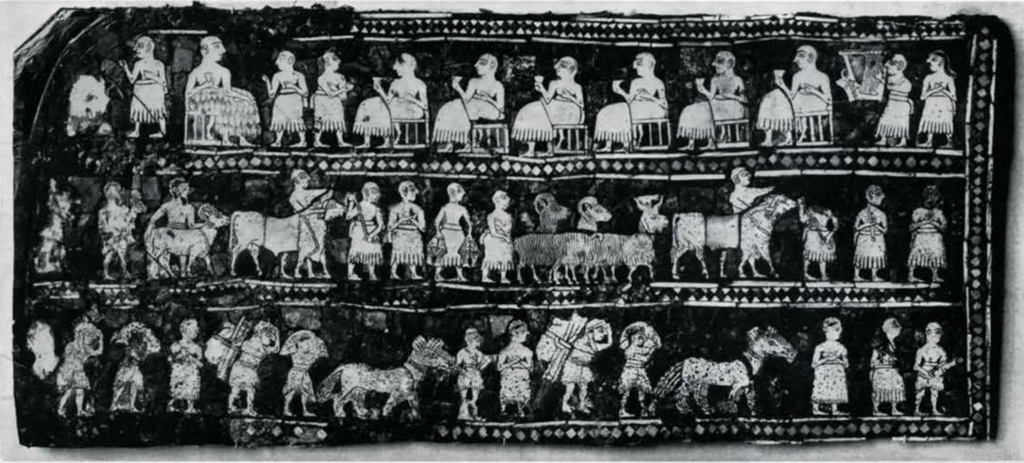

Standard of Ur (c. 2 600 BC to 2 400 BC)

The Standard of Ur (c. 2 600 BC to 2 400 BC) was excavated from the Royal Cemetery at Ur, also during the excavations led by Leonard Woolley. It was found near the shoulder of a man in the corner of a tomb believed to have been dedicated to Ur-Pabilsag, a king during the First Dynasty of Ur during the 26 th century BC.

Woolley suggested the item was used as a standard, which is related to someone carrying an image that relates to a person of high status like a king in this regard.

However, there has been debate as to the real function of this item, some also suggested it was used as a storage box or a sound box. The item was considerably damaged over the centuries from the weight of the soil and the decay of the wood. There have been restoration attempts made to make it appear how it could have looked when it was used.

As we see it now, it is a hollow wooden box measuring 21.59 centimeters in width and 49.53 centimeters in length. There are inlays along each length and end of the box. These are made from red limestone, lapis lazuli, and shell, in a mosaic format. The box’s length is divided into three panels.

What is so unique about this box is that the mosaic inlays are depicted in detail telling a visual story. The narrative and subject matter have been titled “War” and “Peace” because there are figures that relate to the military and other figures that appear to be involved in a banquet.

If we look closer, the “War” panel depicts various figures from the Sumerian army. In the top panel, from the left, we see a man standing by a wagon pulled by four donkeys. There are members of the infantry with cloaks and spears and a central, taller, figure, possibly the king, holding a spear awaiting a procession of oncoming prisoners from the right. Each prisoner seems to be naked and possibly escorted by members of the infantry.

The middle panel depicts what appears to be more members of the army and perpetrators being struck and killed. From the left, there are eight men wearing the same military garments (cloaks and helmets) with weapons. It appears as if they are approaching an ongoing battle that we see depicted on the right side of the panel. The lower panel of the box depicts four wagons led by four donkeys for each. In each wagon, there is a driver and a soldier ready to fight. We will also notice under three of the wagons are dead bodies of the enemies killed from the wagon’s weight and those on it.

The wheels depicted on the wagons are solid structures, a telling portrayal of what it could have looked like in real life.

There is also a dynamism portrayed in the donkey’s stances; from the left, the first wagon with donkeys is seemingly walking, the wagon and donkeys in front of them seem to be going at a bit of a faster pace, otherwise referred to as a canter. The third set of wagons and donkeys appear to be galloping and the last set of donkeys are rearing.

If we look at the “Peace” panels, starting from the top panel, we will see the king on a stool to the left. There are six figures, also seated, holding cups in their right hands, all facing the king, who also holds a cup in his right hand. There are various attendants and a musician holding a lyre, standing as the second figure from the right side. In the middle portion of the “Peace” panel, we will notice various figures ushering in animals that appear to be rams and cows. Some figures also appear to hold fish.

The lower portion of the panel depicts figures with donkeys and packs on the backs, possibly of foodstuffs. These processions of figures from the middle and lower portion of the panel could be on their way to the banquet with offerings towards the feast.

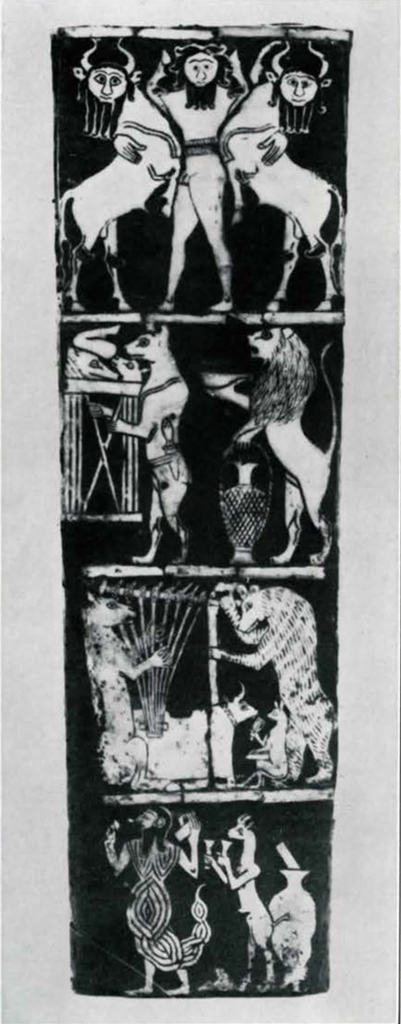

The Queen’s Lyre (c. 2 600 BC)

The Queen’s Lyre (c. 2 600 BC) was found amongst numerous other lyres from the Royal Cemetery at Ur. With a height of 112.50 centimeters and a length of 73 centimeters, this Lyre was found at Queen Puabi’s gravesite. The wood that composed it was damaged from all the years in the gravesite, but it has been restored in various parts. Leonard Woolley reportedly found two lyres in the queen’s grave.

When we look at it more closely, we see the music box is in the shape of a bull. The head and face are gold with lapis lazuli composing the head’s hair, the “beard” of hair under the bull’s face, and its eyes, which are also made from shell. The two white horns are apparently not part of the original, ancient, figure, but modern additions that give us an indication of what it looked like.

As we move further down, what would theoretically be towards the ventral view of the bull’s body, but is really the curving of the music box, we see the similar mosaic panels made from the same material as the above Standard of Ur , shell, red limestone, and lapis lazuli.

This front panel is divided into four squares, each depicting images.

The top image is an eagle with a lion’s head and spread wings with two flanking gazelles. The next image is described by various sources as “bulls with plants on hills”. However, when we look closely these appear like two rams standing on their hind legs reaching up a tree on some sort of basal mound. These are reminiscent of the Ram in a Thicket figurines.

The third square, so to say, depicts a figure with the body of a ram or bull and the torso of a man, holding up two Leopards (or Cheetahs?) by their hind legs. The last square depicts a lion busy sinking its teeth into a bull. There is also a tree shape in the background, similar in appearance to the two trees from the second square.

Warka (Uruk) Vase (c. 3 200 BC – 3 000 BC)

Warka is the modern name for the ancient Sumerian city that was called Uruk. The alabaster Warka Vase (c. 3 200 BC to 3 000 BC) is another example of the beauty of Sumerian carvings. The measurements have been debated for this vessel, as a field book entry from 1934 (when it was found) stated it was around 96 centimeters high, whereas other sources state it is 105 and 106 centimeters high.

Regardless of its measurements, it is safe to say it is around one meter tall. Its diameter is measured as being 36 centimeters.

The Warka Vase was found by a group of German excavators around the years 1933 to 1934. It was in the temple dedicated to the Sumerian goddess called Inanna. She presided over beauty, sex, love, justice, and war. The Sumerian carvings are done as relief carvings and span around the vessel divided into four panels, otherwise known as registers.

Each register depicts different figures and objects from nature; the bottom panel is filled with water at the bottom and growing crops of what appears to be barley and wheat amidst reeds; the second panel depicts rams and ewes. In the third panel, we see nine nude figures of men carrying containers or baskets with food in it. The top panel depicts more characters, including the goddess Inanna and the king.

There are differing ideas as to what narrative the subject matter portrays; some suggest it is a marriage between the king and queen and others that it is a celebration of the queen. This vessel is housed in the National Museum of Iraq.

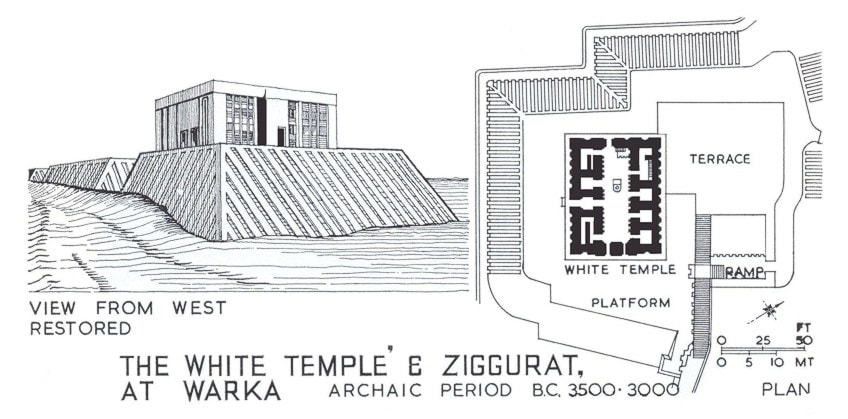

Sumerian Architecture

The Sumerians’ architecture is another important part of not only Sumer culture, but Sumer art. Most buildings were made of clay bricks, a widely spread material. Sumerians were also known as one of the first cultures to undertake urban or city planning. Buildings ranged from houses to palaces and there were different functions, for example, commercial, civic, and residential.

As described from a few examples above, we will typically find a temple as a central building.

The Ziggurat was an important structure, in the shape of a pyramidal tower, or “raised platform”. It was built to venerate the dedicated god or goddess, and a reminder of the political leaders who acted on behalf of that deity, this was a large part of the Sumerian theocratic system.

An example of the above was the White Temple (c. 3517 BC to 3358 BC) built on the Anu Ziggurat in Uruk. Anu was the god of the sky. However, almost over 30 such temples are recorded to exist in various locations around Mesopotamia.

From Writing to Wheels: The Sumerians Remembered

The Sumerian civilization was succeeded by the Akkadians, led by the ruler Sargon of Akkad, from 2334 BC to 2154 BC. After the Akkadian Empire fell there was a period referred to as a “Dark Age” after which there was a resurgence in Sumerian culture with the beginning of the Third Dynasty of Ur (2112 BC to 2004 BC). This was also called the Neo-Sumerian period. It has been compared to a sort of “Golden Age” of the Sumerian Civilization and revival of arts, especially religious arts.

The Sumerians were undoubtedly advanced in many ways, setting the stage for many civilizations to come in so many disciplines in life like art, science, religion, politics, agriculture, and more. They have been lauded as some of the greatest ancient inventors, think of the wheel and writing. And now in our modern-day, we still remember them as a civilization rich in culture, adorned with gems of wisdom just like the art they created.

Take a look at our Sumerian art period webstory here!

Frequently Asked Questions

When was the sumerian period.

Sumer was one of the earliest Mesopotamian civilizations originating before the Akkadian Civilization. Sumer is in the southern part of Mesopotamia and is believed to have been settled around 4 500 BC to 4 000 BC.

What Does “Sumer” Mean?

The name Sumer was given to the Sumerians by the Akkadians. “Black-headed people” or “Black-headed ones” is what the Sumerians used as their name for themselves. The word Kengir , meaning “Country of the Noble Lords” was the name the Sumerians used for their land.

What Kind of Art Was Created in Sumer?

The Sumerians created art from different materials like semi-precious stones, shells, wood, red limestone, metals like gold, silver, and copper, to name a few. These were all used in Sumer paintings and mosaics. Sumerian statues, sculptures, figurines, pottery, and various other objects were also discovered in large quantities by various archaeological excavations. The Sumerians’ architecture and tablets to write on in the cuneiform script were mostly built using clay as this was a widespread and naturally occurring medium.

What Was the Purpose of Sumerian Art?

Sumerian art was beautifully decorated with ornamentations and served religious and sacred purposes. Many of the Sumer art objects were discovered from gravesites and were buried with their respective owners. Temples were important structures and were given great care in construction for the purposes of venerating respective deities.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20 th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team .

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Sumerian Art – The Pottery, Carvings, and Architecture of Sumer Art.” Art in Context. December 8, 2021. URL: https://artincontext.org/sumerian-art/

Meyer, I. (2021, 8 December). Sumerian Art – The Pottery, Carvings, and Architecture of Sumer Art. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/sumerian-art/

Meyer, Isabella. “Sumerian Art – The Pottery, Carvings, and Architecture of Sumer Art.” Art in Context , December 8, 2021. https://artincontext.org/sumerian-art/ .

Similar Posts

Greek Pottery – History of Ceramics in Ancient Greece

Fresco Painting – The Age-Old Art of Applying Paint to Plaster

Form in Art – Exploring the Element of Form through Examples

What Are Artifacts? – The Historical and Cultural Value of Objects

Early Christian Art – Christian Artwork and Biblical Paintings

Caricature Art – The History of Caricature Paintings

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

The Most Famous Artists and Artworks

Discover the most famous artists, paintings, sculptors…in all of history!

MOST FAMOUS ARTISTS AND ARTWORKS

Discover the most famous artists, paintings, sculptors!

Mesopotamian Reed Boats Changed the Stone Age

Emily Hopper / Pexels

- Ancient Civilizations

- Excavations

- History of Animal and Plant Domestication

- M.A., Anthropology, University of Iowa

- B.Ed., Illinois State University

Mesopotamian reed boats constitute the earliest known evidence for deliberately constructed sailing ships, dated to the early Neolithic Ubaid culture of Mesopotamia , about 5500 B.C.E. The small, masted Mesopotamian boats are believed to have facilitated minor but significant long-distance trade between the emerging villages of the Fertile Crescent and the Arabian Neolithic communities of the Persian Gulf. Boatmen followed the Tigris and Euphrates rivers down into the Persian Gulf and along the coasts of Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, and Qatar. The first evidence of Ubaidian boat traffic into the Persian Gulf was recognized in the mid-20th century when examples of Ubaidian pottery were found in scores of coastal Persian gulf sites.

However, it is best to keep in mind that the history of sea-faring is quite ancient. Archaeologists are convinced that both the human settlement of Australia (about 50,000 years ago) and the Americas (about 20,000 years ago) must have been assisted by some sort of watercraft to assist moving people along the coastlines and across large bodies of water. It is quite likely that we will find older ships than those of Mesopotamia. Scholars are not even necessarily certain that Ubaid boat-making originated there. But at present, the Mesopotamian boats are the oldest known.

Ubaid Boats, the Mesopotamian Ships

Archaeologists have assembled quite a bit of evidence about the ships themselves. Ceramic boat models have been found at numerous Ubaid sites, including Ubaid, Eridu , Oueili, Uruk , Uqair, and Mashnaqa, as well as at the Arabian Neolithic sites of H3 located on the northern coast of Kuwait and Dalma in Abu Dhabi. Based on the boat models, the boats were similar in form to bellums (spelled bellams in some texts) used today on the Persian Gulf: small, canoe-shaped boats with upturned and sometimes elaborately decorated bow tips.

Unlike wooden planked bellams, Ubaid ships were made from bundles of reeds roped together and covered with a thick layer of bituminous material for water-proofing. An impression of string on one of several bitumen slabs found at H3 suggests that the boats may have had a lattice of ropes stretched across the hull, similar to that used in later Bronze Age ships from the region.

In addition, bellams are usually pushed along by poles, and at least some of the Ubaid boats were apparently had masts to enable them to hoist sails to catch the wind. An image of a boat on a reworked Ubaid 3 sherd (a ceramic fragment) at the H3 site in coastal Kuwait had two masts.

Trade Items

Very few explicitly Ubaidian artifacts have been found in the Arabian Neolithic sites apart from bitumen chunks, black-on-buff pottery, and boat effigies, and those are fairly rare. Trade items might have been perishables, perhaps textiles or grain, but the trade efforts were likely minimal, consisting of small boats dropping in at Arabian coastal towns. It was a fairly long distance between the Ubaid communities and the Arabian coastline, approximately 450 kilometers (280 miles) between Ur and Kuwait. Trade does not seem to have played a significant role in either culture.

It is possible that the trade included bitumen, a type of asphalt. Bitumen tested from Early Ubaid Chogha Mish, Tell el'Oueili, and Tell Sabi Abyad all come from a wide variety of different sources. Some come from northwestern Iran, northern Iraq, and southern Turkey. Bitumen from H3 was identified as having an origin at Burgan Hill in Kuwait. Some of the other Arabian Neolithic sites in the Persian Gulf imported their bitumen from the Mosul area of Iraq, and it is possible that boats were involved in that. Lapis lazuli, turquoise, and copper were exotics in the Mesopotamian Ubaid sites that potentially could have been imported, in small amounts, using boat traffic.

Boat Repair and Gilgamesh

Bitumen caulking of the reed boats was made by applying a heated mixture of bitumen, vegetal matter, and mineral additives and allowing it to dry and cool to a tough, elastic covering. Unfortunately, that had to be replaced frequently. Hundreds of slabs of reed-impressed bitumen have been recovered from several sites in the Persian Gulf. It may be that the H3 site in Kuwait represents a place where boats were repaired, although no additional evidence (such as woodworking tools) was recovered to support that.

Interestingly, reed boats are an important part of Near Eastern mythologies. In the Mesopotamian Gilgamesh myth, Sargon the Great of Akkad is described as having floated as an infant in a bitumen-coated reed basket down the Euphrates River. This must be the original form of the legend found in the Old Testament book of Exodus where the infant Moses floated down the Nile in a reed basket daubed with bitumen and pitch.

Carter, Robert A. (Editor). "Beyond the Ubaid: Transformation and Integration in the Late Prehistoric Societies of the Middle East." Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilizations, Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, September 15, 2010.

Connan, Jacques. "An overview of bitumen trade in the Near East from the Neolithic (c.8000 BC) to the early Islamic period." Thomas Van de Velde, Arabian Archaeology and Epigraphy, Wiley Online Library, April 7, 2010.

Oron, Asaf. "Early Maritime Activity on the Dead Sea: Bitumen Harvesting and the Possible Use of Reed Watercraft." Ehud Galili, Gideon Hadas, et al., Journal of Maritime Archaeology, Volume 10, Issue 1, The SAO/NASA Astrophysics Data System, April 2015.

Stein, Gil J. "Oriental Institute 2009-2010 Annual Report." Oriental Institute, The University of Chicago, 2009-2010, Chicago, IL.

Wilkinson, T. J. (Editor). "Models of Mesopotamian Landscapes: How small-scale processes contributed to the growth of early civilizations." BAR International Series, McGuire Gibson (Editor), Magnus Widell (Editor), British Archaeological Reports, October 20, 2013.

- The Archaeology and History of Bitumen

- Fast Facts About Mesopotamia

- Timeline and Advances of the Mesopotamian Society

- Ubaidian Culture

- Eridu (Iraq): The Earliest City in Mesopotamia and the World

- Uruk Period Mesopotamia: The Rise of Sumer

- Kuwait | Facts and History

- The Tigris River of Ancient Mesopotamia

- Tell Brak - Mesopotamian Capital in Syria

- An Introduction to Sumerian Art and Culture

- The Most Important Rivers of Ancient History

- An Introduction to Sumer in Ancient History

- What Was the Fertile Crescent?

- Uruk - Mesopotamian Capital City in Iraq

- The Tell Asmar Sculpture Hoard of Prayerful People

- Ancient City of Ur

Old Sumerian Art

By: L. Legrain

Originally Published in 1928

IT is a pure joy for a weary archaeologist to plunge into a study of Oriental art—the oldest known Mesopotamian art—thanks to the rich collection of objects, figures, statues, reliefs, and engravings discovered in the predynastic cemetery at Ur. A new stage of civilization, perfectly unknown a year ago, has now been reached. And to our great surprise, out of the mystery of the past beauty shines with a wonderful glamour. Gold and silver, blue lapis and red carnelian, mother of pearl and shell inlay, lavishly used by the Sumerian artists, show their good taste in the blending of colours, their mastery in the lines of the figures, the boldness and force of their drawings, which have a primitive charm and a subtle refinement such as we find at first hard to reconcile with so early a date. Many of the objects recovered, like the harp, the gaming boards with their sets of ‘men’ and dice, the golden comb so like a Spanish comb, the rings and garter of the queen, the fluted gold tumbler and the chalice, the chariots and their teams, all seem wonderfully familiar and close to us, while the wholesale murder and burial of servants and retainers round the grave of their lord and lady hint at grim customs of hoary ages.

Such beautiful objects were not the work of beginners. Civilization even then was an ancient achievement in Mesopotamia, whence it spread westward. Where shall we look for or place its origin? We do not know. But obviously the old Sumerian art at Ur is already a classical art, with fixed types and school conventions. Modelling, casting, carving, and engraving have no secrets for the expert craftsmen. Their best pieces of work show an ideal of force and dignity not devoid of a certain heaviness, a minute rendering of details, a love of nature and animal life. It is a subtle and curious art which likes inlay and polychromy, delights in the mingling of colours and materials, the blending of low and high relief with boldly salient parts in the round. Its style is surprisingly free and is not abashed by the difficult tracing of figures en face , or the shortening of proportions in perspective. It has even an apparent sense of humour, probably with a deeper meaning, in scenes where animals are given the attitudes and play the parts of men : a dog carries a small altar loaded with offerings, a lion follows him bringing a lamp and the wine of the sacrifice. It is remarkable that the animals are by degrees transformed and given the head, face, locks, beard, arms, feet, and torso of man. We have composite monsters, a bison with a human face, a scorpion-man, a donkey seated and playing the harp with his fingers, a rampant gazelle holding two tumblers, a scaled monkey (?) playing with a rattle and drumming on a board.

This is pure mythology. We are introduced into a world in which animals can play and talk like men : a land of fable such as has always enchanted and will still long delight the children of men. And by the by, that marvellous curled beard hanging below the chin of the man-faced bison is not at all an emblem of divinity, but a sign of human virility. The horned mitre with one, two or four pairs of horns is the only certain emblem of divinity, both for gods and goddesses. So the bull might be a god, even without a beard. The crescent horns are the emblem of the Moon God, called the young bull of heaven. That mighty blue beard simply brings him one step closer to humanity, and may or may not decorate the golden head which animates and gives a voice to the harp “roaring like a bull.”

And here we find a very important link between the old Sumerian art of Ur and the still earlier Elamite civilization—about 4000 B.C.—known through the French excavations at Susa. It is remarkable that the old Elamite artist in all his painting and carving and engraving “never represents a god under human form. But he multiplies animal figures, especially figures of wild species, and gives to them strange attitudes and human gestures. His imagination creates composite monsters, dragons and griffins. And when he reaches a higher stage, it is in scenes where the figures of Gilgamesh and Enkidu are conspicuous and betray a close relation with Babylonia.” 1

“The Gilgamesh and Enkidu contests with wild animals are simply the heroic development of natural hunting scenes by which a contact is established with the archaic or Elamite period. The worshipping of gods in human form with crowns, sceptres, and thrones like kings is a new feature of the Sumero-Akkadian civilisation apparently unknown to the pre-Elamites—and to the predynastic Sumerians of Ur. It supposes regular institutions, city states, courts, and temples modelled on the courts. It expresses a higher ideal of worship no longer limited to stones, animal figures, weapons, and emblems, but to gods akin to humanity.

“Between these two extremes: heroic hunting and regular court worship of the gods, there is a large intermediary layer of mythological figures which seems to connect them and where we see the human god emerging from the beast, or in close contact with the primitive forces of nature. . . . When the gods attained full human stature and royal dignity, the world of heroes and demigods always had a number of bullmen, lionmen, birdmen, fishmen and scorpion-men; while the pure animals: bull, lion, dragon, bird, fish, serpent, scorpion, become simple followers, emblems and servants of the gods.” 2

The eagle, a royal bird, has never attained, as an emblem of divinity, to the popularity of the bull. The eagle triumphs over wild animals, bull, bearded bison, and others. Eagle feathers decorate the heads of Sumerian chiefs, or are an ornament between the horns of the oldest mitre. But they soon disappear and are replaced by two or more pairs of horns, the round crescent horns of the bison, the accepted emblem of divinity. Anthropology and archaeology are both interested in that primitive heraldry. The war eagle of the gods of the atmosphere is the lord of all the creatures of the pasture land. Is not the Moon God like a great bull moving across the pastures of heaven? All Sumer rejoices when his golden horn shines over the horizon, bringing in regular succession months and seasons and years. He is only the son of the god of the atmosphere but he is the guide and teacher of the Sumerian tribes and of their pastors, and his golden crown has impressed them as the highest emblem by which they can distinguish heavenly powers.

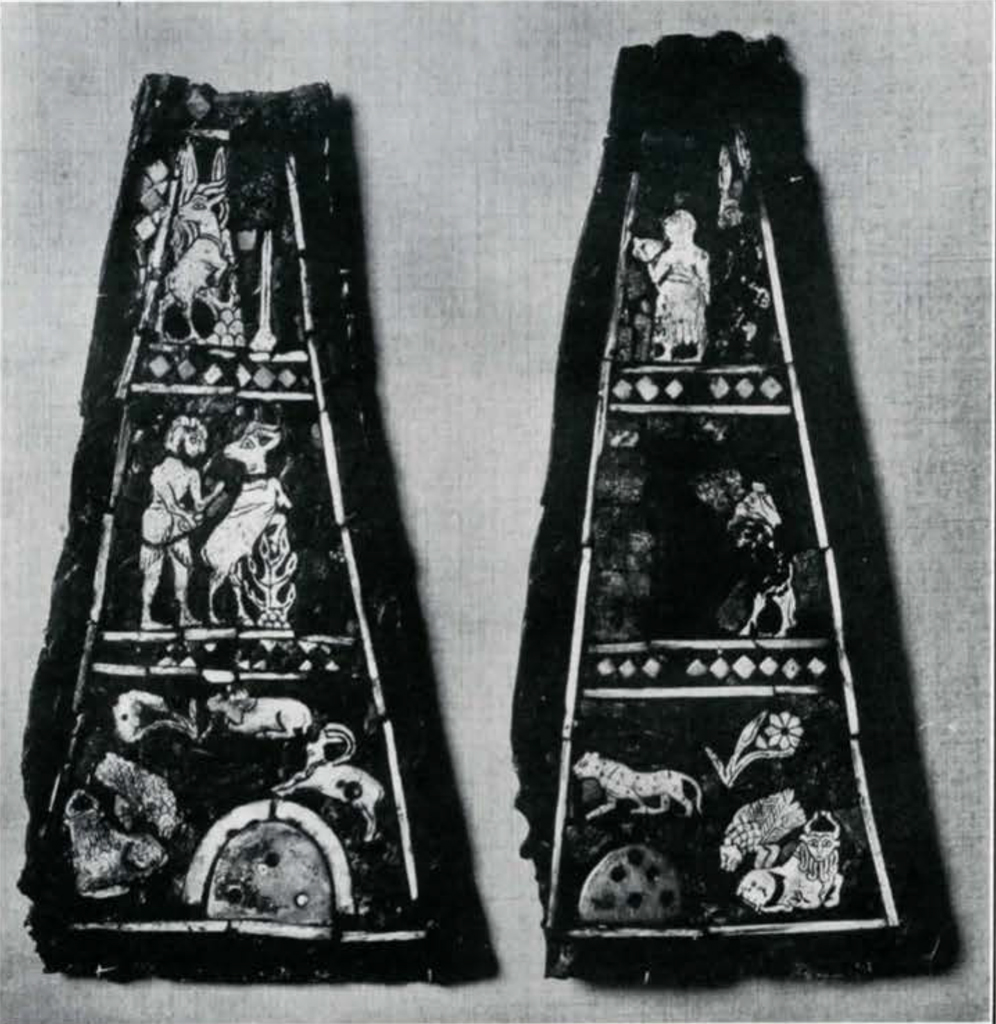

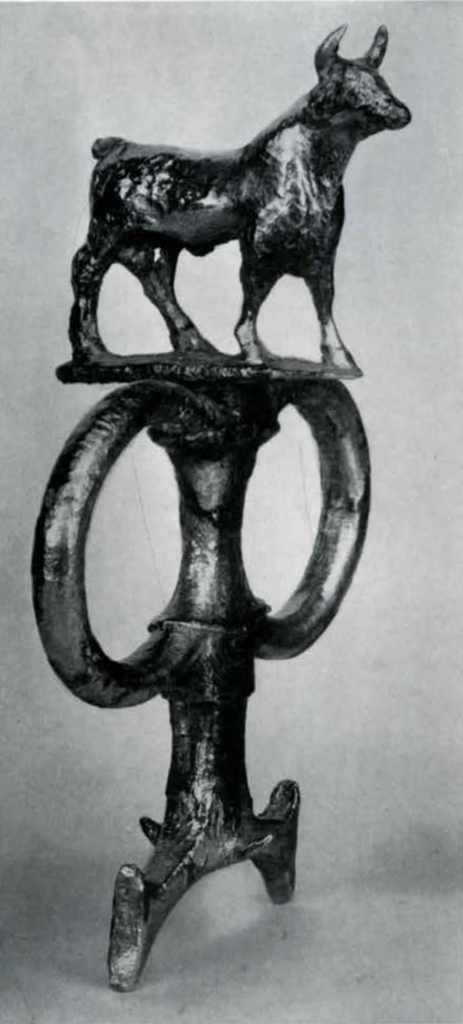

The happy restoration by the British Museum experts of some of the magnificent objects of art taken from the predynastic cemetery at Ur and their recent publication will be welcome to the readers of the JOURNAL. They will admire the stela or standard with six rows of Sumerian figures and scenes of peace and war cut in shell and inlaid on a background of blue lapis; the sounding-box of a harp decorated with inlay, engraved plaques, and a bull’s head in gold and lapis; another bull’s head in gold and lapis, part of a statue or probably of a second harp; finally a rein ring in silver surmounted by a bull mascot from the king’s wagon. In the field of the past, the mist is slowly lifting, leaving a bright golden spot in the muddy plains of Mesopotamia, where Shub-ad was once a queen and Meskalamdug a king in ancient Ur, more than five thousand years ago.

The Inlay Stela

It seems almost impossible ever to satisfy our curiosity by looking at the world of little Sumerian figures crowded in the six registers of the stela and in the two triangular ends. The whole is only 32 inches long, but there is such a variety of action, such a sense of life, with so many different costumes of the king, of his officials and his servants, such a display of arms, cloaks and helmets, such a contrast between the victors and their tattooed enemies, such a fascination about the chariots, their drivers, their men-at-arms, their teams of asses and their harness, that we gaze again and again, afraid to miss a single detail of that wonderful picture of ancient Sumerian life. The king is the real war lord. His figure is drawn on a larger scale and stands in the middle of the upper register. He carries in the right hand a curved club, his sceptre, and in the left, a lance with a large leaf-shaped head. Prisoners are brought one by one to him, and foremost one who is probably the chief of the defeated enemies. The king has alighted from his chariot and is followed by his bodyguard or by officials of high rank, armed with battle-axe and lance. The king, his guard, and his soldiers all wear copper helmets covering the ears and tied with a strap below the chin. Some of the original helmets have been recovered in the excavations and the type strangely recalls some helmets of the crusaders’ time. Lances and axes also have been recovered of the very type represented on the stela. The best gold models must have been the weapons of the king. The proper Sumerian dress is a kilt with long laps, closing behind. Originally a fleece, it may later have been made of woollen material with long thrums woven in on one side in imitation of the fleece. A second piece of the same material—called kaunakes —was thrown like a plaid over the left shoulder. The whole army was shaven and shorn according to Sumerian tradition, and went barefooted, which was no inconvenience on the soft muddy soil of Mesopotamia. Of course a wadded lining was fixed inside the helmet; traces of one have been found inside the golden wig.

The king’s chariot is of the common type of that age, with four wheels, side and back panels, a high front board, and a curved pole rising high and supporting a rein ring behind its junction with the yoke. A diminutive groom, his whip resting on his shoulder, leads the royal team of great mules or asses. The man-at-arms or henchman follows on foot behind, holding the reins in his left and his battle-axe in his right hand. The reins lie in the V-shaped notch cut in the top of the front board. A large quiver full of spare darts and lances hangs on the left horn of the same board. A leopard skin or blanket is thrown over the back panel and covers the step on which the second charioteer will stand during the action, protecting the driver fighting in front. The front board is reinforced by cross pieces, the sides are divided into three panels by straight bars. State chariots decorated with an inlaid pattern of shell and lapis, and lions’, bulls’ and leopards’ heads in gold and silver in the round have been recovered in the royal tombs. These were not war chariots but rather belong to the sumptuous type of coach which Ishtar devised as a reward for her lovers: “I will harness for thee a chariot of lapis and gold, with wheels of gold and horns of diamond. Daily shalt thou harness the great mules.”

Ishtar herself, the august princess of Uruk, who inhabits a house of gold, drove a team of seven lions. But this is pure mythology. The king’s own team was incontestably a team of four mules or donkeys. For the first time we have a clear, complete picture of the animals with body, hoofs, head, and tail, and they are neither horses nor lions nor bearded bulls nor dragons, but asses, which is very satisfactory. What seems to be the long hair round their necks is neither mane nor beard, but artificial braids of hair or wool attached to the collar like an ornament or to drive flies away, a practice very much in honour among the Assyrians and still observed in many parts of the world. The reins were attached to a ring in the animal’s nose. Silver collars and silver rings have been found in the royal graves, providing evidence that teams of bulls were used as well as teams of asses.

The plain wooden wheels made of two semicircular pieces joined by copper clamps or bands round a central core, have excited the enthusiasm of archaeologists. The wheel, a great human discovery, was in use at Ur more than fifteen hundred years before it was imported into Egypt. There are several models of wheels which show that the central core was either round or lozenge-shaped. The wheel was probably solid with the axle which turned with it in a groove below the body of the chariot. A copper pin or bolt sometimes secured its connection with the axle. In any case the early Sumerian wheel was massive and not yet made more graceful or lighter by the use of spokes. Big knobs of metal sometimes rein-forced the rim. Mr. Woolley has suggested leather tires. The only wheelband discovered at Susa was made of six bronze sections riveted together and forming a complete circle embedded in the rim.

Centuries later Gudea, another prince of Sumer, was ordered to build the royal chariot of his god: “Break the seal (of the doors) of thy treasure house; bring wood out of it, and build a complete chariot for thy king. Harness to it the donkeys. Adorn the chariot with metal and lapis inlay. Darts in the quiver shall shine like the day. Take good care of the ankar , the arm of bravery.” Gudea brought out his most precious timber, esalim-wood, mêsu-wood, huluppu-wood. He completed the chariot and harnessed to it the great Uk-kash donkeys. The chariot shone like the stars in heaven. The donkeys were of the famous breed of Eridu, and the driver Ensignun could drive like a storm. It was an irresistible machine of war: ” The chariot named Kurmugan, was loaded with splendour, covered with brilliancy. With its donkeys, its groom, the seven-headed club, the terrible weapons of the battle, the weapons which no country can resist, the deadly weapons of the battle, the Mi-ib, with a lion head in hulalu stone which no land resists, the sword with the nine emblems, the arm of bravery, the bow which sounds like a (forest), the terrible arrows of the battle which dart like lightnings, the quiver out of which wild beast and dragons let hang their tongues, arms of the battle to fulfil the orders of royalty, all this was a present of Gudea, builder of the temple, patesi of Lagash.”

All the prisoners brought in to the king are nude except the first of them, who wears a short fringed kilt, but he is so indistinct a figure that it is hard to decide whom he represents, probably the enemy king. All have ropes round their necks and their arms tied behind their backs. They are shaven and shorn like their Sumerian opponents and it would have been difficult to distinguish one from another if the enemies did not have marks—war paint or tattoo?—all over the body, on skull, cheek, chest, and thigh. Or are these marks of the wounds inflicted by the battle-axes and lances which we see in the hands of the soldiers, a graphic representation of the blood trickling from the cuts in the flesh? There is a certain freedom of style in that otherwise monotonous procession. Not one figure is the exact copy of the other. The groups are not rigidly the same. Two prisoners are marshalled by one man—if this is the original order? All the soldiers do not carry the same weapon. Their proud attitude, with heads erect, contrasts with the downcast look of the prisoners.

The army in action is displayed in the next two registers. It is divided into two corps, the foot troops and the charioteers. And we cannot help admiring the free imagination, the naive charm in the forceful presentation by the primitive artist of a battle scene so full of life and motion. The solid legion has formed a line with lowered lances pointing forward. All wear the uniform : the scalloped kilt, the copper helmet fixed by a strap under the chin, a mantle covering both shoulders and fastened by a clasp on the chest. The dots in groups of three, four, and five which decorate the mantles make the soldiers look like the pieces of a game of dominoes, giving somehow the impression of knaves in a pack of cards, which would have pleased Alice in Wonderland. In fact these are not dots but the spots of leopard skins, as we see from the animal represented on the triangular end. The skin served as a material for the soldiers’ heavy coat, which was thrown over the back of the chariot when not used, or spread on the seat as a blanket. 3 Nothing could disturb the order of this solid rear line. Their grasp on their lances betokens perfect drilling, and while the practised eye of a sergeant-major might see irregularity in the openings of the mantles, the ordered tramp, tramp of their feet would have swollen with pride the builder of an empire. Three sons of an old Sumerian king on a famous limestone relief 4 wear their mantles in the same manner, fastened with a clasp and covering both shoulders. The soldiers of the front line are already engaged in an action, the issue of which is not doubtful. The enemies are prostrate, wounded, stripped, bound, and captive, so dexterously can the Sumerian warrior handle battle-axe and lance, as shown in three different groups. One prisoner is being handcuffed. The soldier next to him brandishes his lance over a fallen enemy. The third wipes the blade of his axe and feels the cutting edge after dealing a blow. The bodies of the fallen enemies are drawn with much liberty and a daring attempt at perspective and foreshortening of proportions, both here and in the case of the bodies of the enemies run down by the charioteers. The Sumerian soldier in action has discarded his great mantle and thrown his plaid over his left shoulder. A fringed stole over the left arm of one of them is an unusual garment, perhaps the loin cloth of the enemy and a part of the spoil which belongs to the victor. More enemies, nude and wounded, are driven on by the charging infantry. Some of them still keep their lances and their loin cloths closing in front and having narrow fringes. The fight is over and they are fleeing, while one unfortunate man casts a last look on the scene of battle. This part of the stela has evidently suffered and two half figures of men, one nude and the other wearing a loin cloth, have been jumbled together.

The charioteer scene is a pure delight for anybody who has witnessed a charge and the long lines of horses sweeping, wave after wave, through the golden dust. If the first team of asses walks composedly enough, the second has struck a lively pace which becomes a full gallop and a mad dash in the last two. The foremost driver with his goad or two-pronged dart and his henchman brandishing a lance is thrown backwards and the man on the step has to hang on desperately. Their raised heads answer to the raised heads of the animals, to their springing bodies and their flowing tails. Weapons, lances, axes, dresses, helmets, kilts, and plaids are the same as those worn by the infantry. The crumpled nude bodies of the enemies litter the ground.

The reverse is not less interesting. Here we see the pleasures and abundance of peace opposed to the violence of war. The king presides over a banquet amidst his sons or officials and drinks a cup of the best mountain wine. The seats are remarkably elegant. Servants hustle about and a woman singer, we imagine, recites in cadenced verses the great actions of the battle accompanied by the harpist striking in time the eleven cords of his small harp. So the women danced, and sang that King Saul had killed his thousand but David his ten thousand. In the registers below there is a real pageant of servants bringing the requisites of the feast and also the spoils of war. Bulls, goats, a ram, a lamb, and four big carp fresh from the river will supply a royal meal. The safe leading of the lively bulls is no easy matter. A rope is attached to a ring in the beast’s nose, and the first cowboy pulls it high to prevent any unruly tossing, while the second has wound his arms, like a wrestler, round the threatening horns of the bull, ready to throw it. What would our Wild West think of that ancient East? The manner in which the shepherds carry a lamb—or is it a young gazelle?—or hold a ram by the curved horn and fat tail has not changed since those early days. The goat-herd armed with a short stick or a whip drives his animals from behind. For accuracy the heads of the goats nos. 2 and 3 ought to be placed a little forward to balance properly over their forelegs. Goat no. 1 belongs to a different species, the Markhur goat, with spiral horns, long pendent ears, a beard, and a tucked-up tail. A headman carrying his staff of office introduces the procession, which is divided into two main groups headed by figures with clasped hands. These have no special attributes and are perhaps foremen or officials.

In the last register two teams of asses with their drivers, and pack carriers of two types are divided into two or three groups headed by their foremen, if such are the figures with the clasped hands. The first driver walks rope in hand at the head of the procession and evidently ought rather to be placed at the head of his asses, which is his proper station as exemplified by the second driver. One of the pack carriers bears the bundles on his shoulder but the second uses a framework resting on his back and secured by a rope passing round his forehead. This way of carrying heavy burdens strangely recalls Indian basket carriers or jar carriers from old Peru. The carriers and the foremen have long hair, the asses’ drivers are shorn like the rest of the servants above, except the men who bring the lamb and the ram, who wear long hair and beards. This may be a professional as well as a racial distinction. Bedouin shepherds in the desert let their hair grow. But slaves and prisoners of war of different races may have kept their own mode of hairdressing and costume. It is remarkable that all the figures in the last register wear a kilt closing behind or a loin cloth opening in front, with short fringes. The kilt with short fringes is very different from the kilt with long laps worn by the Sumerian officials, or from the better one worn by the king. The loin cloth opening in front is the proper dress of the vanquished enemies. The careful drawing may correspond to a difference in race and rank and also to a difference of material, wool or linen. The only figure—unfortunately incomplete—in the third register who wears the Sumerian kilt with long laps which closes behind, is probably another headman introducing the second procession.

Animal figures borrowed from the common repertory of heraldry and heroic hunting fill the triangular ends of the stela. We have the passant leopard, the couchant lamb, the rampant goat, the conventional branch and star flower with eight petals, in a landscape of hills represented by a pyramid of dots or curves. A hunter, dagger in hand, has seized about the neck a rampant ibex caught amidst bushes and hills. The hunter may be a hillman, an Elamite, with long hair and beard (?), very different from the completely shorn Sumerian. He wears the fringed loin cloth of the enemy, closing in front. The lines of his body are more elongated and graceful, the knees are bare for action. The typical, shorn, stumpy Sumerian wears a bell-shaped woollen kilt closing behind. The long laps hang down the middle of his legs. The panels are reconstructed and the scene is not clear, but he is certainly not a hunter, and is probably raising his hand for some ritual action. The goat rampant amidst bushes and hills with head turned back is probably out of position, and the straight post supporting an emblem 5 is the object which ought to have been placed in front of the Sumerian worshipper. The middle, incomplete panel certainly represented a fight between bull and lion as seen below in the decoration of the harp.

The very ancient mythological group of the lion-headed eagle perched on the back of the bearded, man-headed bison, which he masters and lacerates “unguibus” if not “rostro,” deserves special attention. The composite monsters are in the tradition of archaic Elamite art. The mythical bird is the master of the bull. By no means is he picking off flies and bugs as has been irreverently suggested. The eagle is above all an emblem of royalty, domination, and power, and such has been his meaning through the ages, whether he flies over the heads of Assyrian kings, or before Roman legions, or on Greek, German, French, or American coins. The spread-eagle found in so many coats of arms of old Sumer and of modern countries is the triumphant bird seizing its prey with its talons. He is the emblem of gods of war worshipped in different cities under different names, Ningirsu, Nin-Urash, In-Shusi-nak. Under the name of Imgig he figures in the coat of arms of the city of Lagash, devoted to Ningirsu, where the type of an eagle with a lion’s head is well established and is contemporary with the drawing of many figures in full face. But there was more liberty in the past and we find spread-eagles and eagles in profile, with normal heads and with lions’ heads, capturing two animals or perching on the back of one. Their prey may be bulls, antelopes, lions, stags, ibexes, even ducks.

The bull may be passant, couchant, or rampant. It may be the wild mountain bull with widely spread horns, the primitive urochs, or the bison with crescent horns and long locks, which in old Elamite drawings has tufts of hair below the chin. The last has been transformed into the man-headed bison which has the face of Gilgamesh, before it becomes the bull-man Enkidu. The spread-eagle may even have a double lion’s head, which was a favourite device in the time of Gudea and on a few ancient Elamite seals, but he should not be confused with the birdman Zü, who steals the tablets of destiny, carries the dead bison on his shoulders, has a wife and son, and is killed by Lugalbanda in Khashu, the unknown mountain. Many a seal in the Museum collections represents the capture and judgment of the Zü bird and his disgrace, which can never be imputed to the royal Imgig bird.

The inlay stela, 6 according to Mr. Woolley, is as a work of art unparallelled, as a historic document invaluable. It was found beside the shoulder of a man buried in a side chamber of the oldest of the royal tombs, almost intact as it was executed by the craftsmen of 3500 B.C. It is an elaborate example of inlay work in shell, lapis lazuli, and pink limestone. The two large plaques were set back to back at a slight angle, with the triangular pieces between their ends, and the whole may have been mounted on a pole so as to be carried as a standard. The tesserae had for the most part not shifted from their position. What is shown here is not a reconstruction but the original mosaic. Some of the border has been restored; only the triangular ends had been seriously broken up.

The harp is the instrument of the poets, the support of the aerial words in which they enshrine joys and sorrows, memory of the past and hope immortal. David sang to the harp to soothe the brooding heart of Saul. A harpist and a woman singer stand by at the king’s banquet. Gudea of Lagash presented to his god Ningirsu “his beloved harp named Usumgal-kalamma, the sonorous and famous instrument of his council. The portico (?) of the harp was like a roaring bull.” It served to accompany the sacred prayers which were said in the court, together with the clang of the cymbals. “Along with the flute it filled with joy the courts of the temple.” The temple singer used it “to appease the heart, to please the joyous humour, to wipe tears from the eyes, to release the pain of the suffering heart.” The singer in his recital is likened to “the storm of the Ocean, to the tempest on land, to the soft purifying waters of the Euphrates. The young girls of the harem, the seven twins of the goddess Bau, placed close to him, pronounce the good words. With the flute, the cymbals, and the harp they fill with joy the courts of the temple.”

The harp of Gudea is represented on a limestone relief. It is rectangular in form, with a large sounding-box and an upper bar in which the keys are fixed. It has eleven strings spreading fanwise from the box to the upper bar, towards the left angle behind which sits the player, playing with both hands. A passant bull, probably of gold, stands on the sounding-box, and another bull’s head decorates the front of it.

The little harp represented on the stela also has eleven strings, and is decorated with a bull’s head. The sounding-box has the shape of a couchant bull, with an inlaid collar and an inlaid band across the body. The harpist plays while standing. A band passing over his shoulders may help to carry the instrument. An opening in the sides of the box makes the sounds clearer and mellow.

Another type of harp with eight strings is represented on a shell plaque to be studied below. It is played by a seated donkey and belongs to a very interesting mythological series. With three other plaques it was inset as a decoration below the splendid horned bull’s head in gold, with its large beard of lapis. Bull’s head and plaques were possibly part of a harp of the same type.

The harp found in the queen’s grave had also a sounding-box decorated with a calf’s head of gold and lapis, with shell plaques engraved with mythological subjects, and with bands of inlay. 7 The woodwork, which had perished, has been carefully restored in the British Museum. According to Mr. Woolley the harp has twelve strings, but the position of the keys on the upright is not clear, pending further restoration. The calf’s head and the engraved plaques deserve attention.

The calf’s head, without horns, which decorates the queen’s harp, is made of gold and lapis, like the bull’s head found in the king’s grave, which may also have been part of a harp. Both are wonderful examples of ancient Sumerian art. The same technique was applied to both.

“The head all except the ears and horns was hammered up from a sheet of thin gold and set over a wooden core. The horns and ears made separately were fixed to this. Under the chin a deep cut was made in the wood, the edges of the gold being bent into the cut, and here was inserted the beard. The base of this was a wooden board on which the tresses cut of lapis lazuli were set in bitumen, while the back and sides of the board were concealed by a plate of thin silver seamed by silver nails. The upper part of the woodwork went right up into the wood of the head and was made fast to it by nails driven through the crown. The gold did not cover the crown at all. Here the wooden core left exposed was coated with bitumen and into the bitumen were laid the lapis lazuli locks of hair, each separately carved.

“The eyes of white shell with lapis pupils enclosed in eye sockets of lapis were secured by copper bolts to the wood core of the head. The many superciliary folds are typical of Sumerian art. A strip of gold nailed on behind the horns completed the neck and a narrow band of mosaic in shell and lapis formed a collar to mark the distinction between the metal head and the wooden body.”

These are beautiful pieces of work, curious and refined. The association of full and low relief with engraving betrays the very spirit and taste of ancient Sumerian art. The result of such inlay is very striking. The polychromy of the materials, shell, lapis, gold, red limestone, and bitumen adds new unforeseen effects. The animal forms are heavy but original and powerful. The types, studied from nature in familiar attitudes, are strikingly true. The first sketch fixed the essential forms of each species. The artists of the best periods will have nothing to change to reach perfection, more refinement but not more character.

Animal life is a favourite motif of Sumerian art. The animals are drawn in familiar poses, couchant, rampant, running, fighting, according to well-established types. Legendary and fantastic compositions alternate with these monotonous repetitions: lion-headed eagle, bearded bull, scorpion-man.

Sumerian religion gave a large place to spirits, demons, genii, embodying natural forces. This religious and primitive instinct of the race inspired the artists to create monsters, fantastic beings composed of several animal forms, which were sometimes combined with human forms. In Elam long before, when no god had ever been represented as a man, the animals were given strange human attitudes, in an effort to express the mens divinior .

The bearded bison was known to and represented by Elamite artists, with graphic details of locks and tresses, which the wild bull can never claim. But the actual blue lapis beard below the golden head is a human attribute of the hero-hunter Gilgamesh, mighty as Nimrod. The proper attribute of the gods, under human form, is the horned mitre. It is true that the great Moon God of Ur is called the young bull of heaven and his blue lapis beard is famous in religious poems. But the divine harp, Usum-kalamma, roaring like a bull, is not necessarily the great Moon God Nannar or any great bull of heaven.

The front of the harp below the golden calf’s head is decorated with four shell plaques engraved with animal figures, in natural or fantastic composition. Engraving on shell is a purely Sumerian art. The drawing is done with a hard point on dull shell with scarcely visible relief. The plaques of shell of small dimensions were cut from the pivot axis of certain univalve shells of the species trito or melo . Drawing with the point is the most primitive, the simplest, and the most abstract form of art. Bodies are reduced to a single contour line with no thickness. Engraving and drawing are one at first, whether on metal, shell, or mother of pearl. Strength is the ideal of the engraver. His tracing is surprisingly strong, somewhat heavy but full of expression, done with a very accurate hand, but cutting a uniform line. Even inside the contour, the tracing of muscles or the detail of manes and feathers is not a shade lighter. The ambition of the artist is strong uniform work in sharp contrast on the white background. The filling of the lines with black and red paint betrays his delight in life and colours.

Each subject is framed by a straight border line. The intentional order of the figures, the need for symmetry and the heraldic composition of confronted animals is from the beginning the characteristic mark of Sumerian decorative art. Figures en face , always very difficult, and the abundance of minute and systematic details are a daring attempt at reproducing life. There is the same power in the daring attitudes, the heads turned full face, the raised tails, the bristling manes full of a rude energy.

The four subjects selected are the lion-headed eagle seizing two leaping ibexes—or antelopes (?); two bulls rampant in a thicket of plants; the bull-man Enkidu holding up two leopards by their hind legs; a hunting lion at grips with a rampant bull, seizing its neck in its jaws.