The Voyage of the Granma and the Cuban Revolution

Fidel Castro's Epic Sea Odyssey

AFP / Getty Images

- Caribbean History

- History Before Columbus

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Central American History

- South American History

- Mexican History

- American History

- African American History

- African History

- Ancient History and Culture

- Asian History

- European History

- Medieval & Renaissance History

- Military History

- The 20th Century

- Women's History

- Ph.D., Spanish, Ohio State University

- M.A., Spanish, University of Montana

- B.A., Spanish, Penn State University

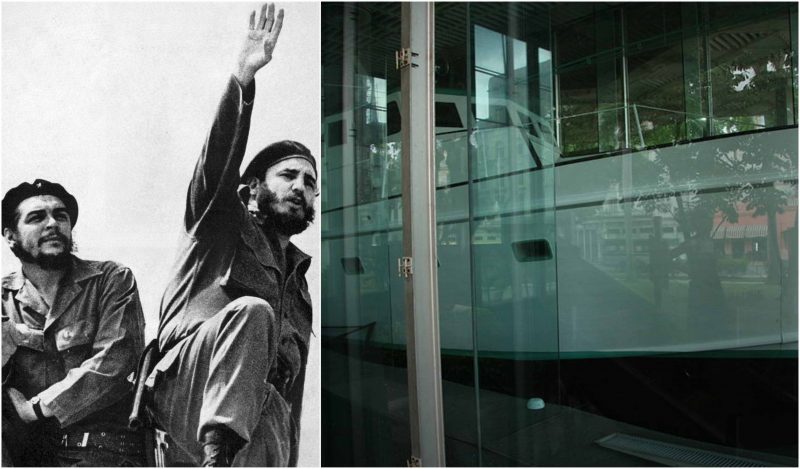

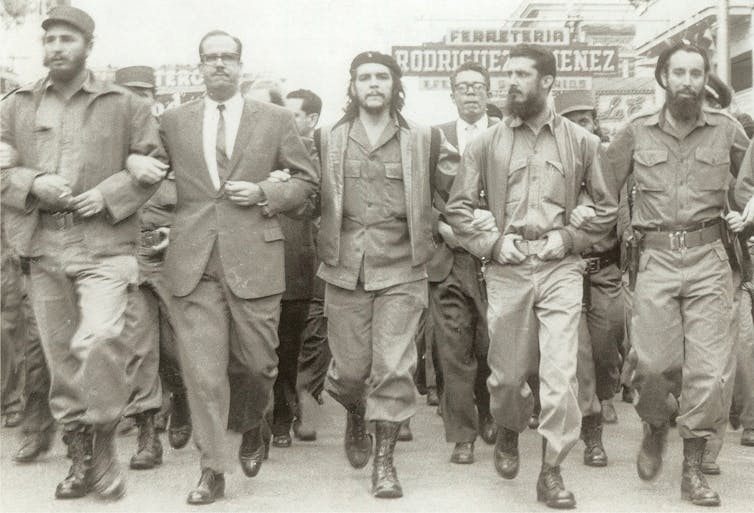

In November 1956, 82 Cuban rebels piled onto the small yacht Granma and set sail for Cuba to touch off the Cuban Revolution . The yacht, designed for only 12 passengers and supposedly with a maximum capacity of 25, also had to carry fuel for a week as well as food and weapons for the soldiers. Miraculously, the Granma made it to Cuba on December 2 and the Cuban rebels (including Fidel and Raul Castro, Ernesto “Ché” Guevara and Camilo Cienfuegos ) disembarked to start the revolution.

In 1953, Fidel Castro had led an assault on the federal barracks at Moncada , near Santiago. The attack was a failure and Castro was sent to jail. The attackers were released in 1955 by Dictator Fulgencio Batista , however, who was bowing to international pressure to release political prisoners. Castro and many of the others went to Mexico to plan the next step of the revolution. In Mexico, Castro found many Cuban exiles who wanted to see the end of the Batista regime. They began to organize the “26th of July Movement” named after the date of the Moncada assault.

Organization

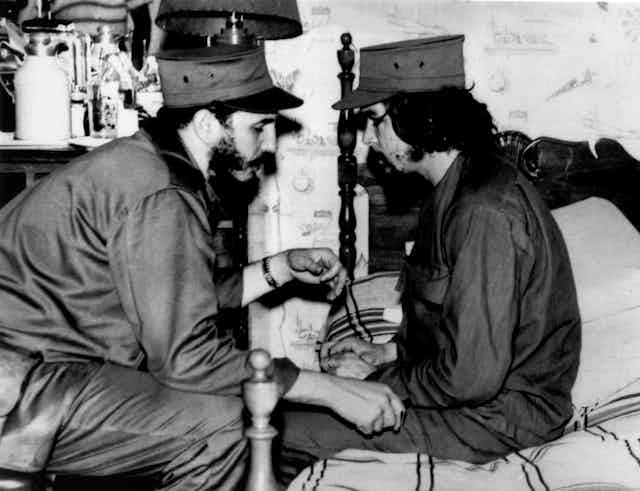

In Mexico, the rebels collected arms and received training. Fidel and Raúl Castro also met two men who would play key roles in the revolution: Argentine physician Ernesto “Ché” Guevara and Cuban exile Camilo Cienfuegos. The Mexican government, suspicious of the activities of the movement, detained some of them for a while, but eventually left them alone. The group had some money, provided by former Cuban president Carlos Prío. When the group was ready, they contacted their comrades back in Cuba and told them to cause distractions on November 30, the day they would arrive.

Castro still had the problem of how to get the men to Cuba. At first, he tried to purchase a used military transport but was unable to locate one. Desperate, he purchased the yacht Granma for $18,000 of Prío’s money through a Mexican agent. The Granma, supposedly named after the grandmother of its first owner (an American), was run down, its two diesel engines in need of repair. The 13 meter (about 43 feet) yacht was designed for 12 passengers and could only fit about 20 comfortably. Castro docked the yacht in Tuxpan, on the Mexican coast.

At the end of November, Castro heard rumors that the Mexican police were planning to arrest the Cubans and possibly turn them over to Batista. Even though repairs to the Granma were not completed, he knew they had to go. On the night of November 25, the boat was loaded down with food, weapons, and fuel, and 82 Cuban rebels came on board. Another fifty or so remained behind, as there was no room for them. The boat departed silently, so as not to alert Mexican authorities. Once it was in international waters, the men on board began loudly singing the Cuban national anthem.

Rough Waters

The 1,200-mile sea voyage was utterly miserable. Food had to be rationed, and there was no room for anyone to rest. The engines were in poor repair and required constant attention. As the Granma passed Yucatan, it began taking on water, and the men had to bail until the bilge pumps were repaired: for a while, it looked as if the boat would surely sink. Seas were rough and many of the men were seasick. Guevara, a doctor, could tend to the men but he had no seasickness remedies. One man fell overboard at night and they spent an hour searching for him before he was rescued: this used up fuel they could not spare.

Arrival in Cuba

Castro had estimated the trip would take five days, and communicated to his people in Cuba that they would arrive on November 30th. The Granma was slowed by engine trouble and excess weight, however, and didn’t arrive until December 2nd. The rebels in Cuba did their part, attacking government and military installations on the 30th, but Castro and the others did not arrive. They reached Cuba on December 2nd, but it was during broad daylight and the Cuban Air Force was flying patrols looking for them. They also missed their intended landing spot by about 15 miles.

The Rest of the Story

All 82 rebels reached Cuba, and Castro decided to head for the mountains of the Sierra Maestra where he could regroup and contact sympathizers in Havana and elsewhere. In the afternoon of December 5th, they were located by a large army patrol and attacked by surprise. The rebels were immediately scattered, and over the next few days most of them were killed or captured: less than 20 made it to the Sierra Maestra with Castro.

The handful of rebels who survived the Granma trip and ensuing massacre became Castro’s inner circle, men he could trust, and he built his movement around them. By the end of 1958, Castro was ready to make his move: the despised Batista was driven out and the revolutionaries marched into Havana in triumph.

The Granma itself was retired with honor. After the triumph of the revolution, it was brought to Havana harbor. Later it was preserved and put on display.

Today, the Granma is a sacred symbol of the Revolution. The province where it landed was divided, creating the new Granma Province. The official newspaper of the Cuban Communist Party is called Granma. The spot where it landed was made into the Landing of the Granma National Park, and it has been named a UNESCO World Heritage Site , although more for marine life than historical value. Every year, Cuban schoolchildren board a replica of the Granma and re-trace its voyage from the coast of Mexico to Cuba.

Resources and Further Reading

- Castañeda, Jorge C. Compañero: the Life and Death of Che Guevara. New York: Vintage Books, 1997.

- Coltman, Leycester. The Real Fidel Castro. New Haven and London: the Yale University Press, 2003.

- A Brief History of the Cuban Revolution

- Biography of Camilo Cienfuegos, Cuban Revolutionary

- Biography of Raul Castro

- Key Players in the Cuban Revolution

- Biography of Fulgencio Batista, Cuban President and Dictator

- Biography of Ernesto Che Guevara, Revolutionary Leader

- Cuban Revolution: Assault on the Moncada Barracks

- Biography of Fidel Castro, President of Cuba for 50 Years

- Cuba: The Bay of Pigs Invasion

- A Short History of the Chinese in Cuba

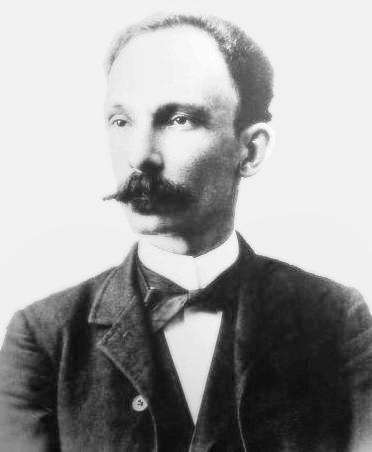

- Biography of José Martí, Cuban Poet, Patriot, Revolutionary

- Civil Wars and Revolutions in Latin American History

- Most Impressive Facial Hair in the History of Latin America

- US and Cuba Have History of Complex Relations

- The 10 Most Important Events in the History of Latin America

- USS Maine Explosion and the Spanish-American War

Granma Yacht: the vessel which brought the Cuban Revolution in Cuba

On November 1956, Fidel Castro, Che Guevara, Camilo Cienfuegos, and Castro’s brother, Raul Castro, along with 80 other fighters, departed from the Mexican port of Tuxpan, Veracruz and headed to Cuba on the yacht “Granma.” The 60-foot (18 meters) diesel-powered cabin cruiser, originally designed for twelve people, brought the Cuban revolutionaries who overthrew the regime of Fulgencio Batista.

The cruiser was built in 1943, and it is said that it was originally named after the grandmother of the original owner. However, the revolutionaries called the yacht simply “Granma,” as an affectionate term for a grandmother. The yacht was purchased only a month before the revolution, on the 10th October 1956. It was bought from the United States for MX$ 50,000 (US$15,000), through a gun dealer Antonio “The Friend” del Conde from Mexico City.

Castro’s initial plan for crossing the Gulf of Mexico was to purchase a US naval crash rescue boat or a Catalina flying boat maritime aircraft. However, he wasn’t able to realize his idea due to the lack of funds. The money for the “Granma” yacht was donated to the revolution by the former Cuban President Carlos Prío Socarrás and Teresa Casuso Morín, a prominent Cuban intellectual, and writer, who fought for freedom and democracy in Cuba.

The Cuban Revolutionaries, later known as “Los expedicionarios del yate Granma” (“The Granma yacht expeditioners”) set out from Tuxpan shortly after midnight, on the 25th November. For more than a week, the members of the expedition experienced sea-sickness, diminishing supplies, and a leaking craft until the 2nd December, when the 82 revolutionaries arrived on Playa Las Coloradas, municipality of Niquero, today known as Granma Province. The location was chosen by the Cuban national hero, Jose Marti.

The site was chosen by the Cuban national hero, Jose Marti. He had landed at the very same location 61 years earlier, during the independence wars from the Spanish colonial rule. The yacht was navigated by Castro’s ally and the Cuban Navy veteran, Norberto Collado Abreu.

Here’s what Che Guevara has written about the landing: “We reached solid ground, lost, stumbling along like so many shadows or ghosts marching in response to some obscure psychic impulse. We had been through seven days of constant hunger and sickness during the sea crossing, topped by three still more terrible days on land. Exactly ten days after our departure from Mexico, during the early morning hours of December 5th, following a night-long march interrupted by fainting and frequent rest periods, we reached a spot paradoxically known as Alegría de Pío (Rejoicing of the Pious)”. Ernesto “Che” Guevara (World Leaders Past & Present) by Douglas Kellner, 1989, Chelsea House Publishers, pg 40.

After the triumph of the revolution on 1st January 1959, the yacht was transferred to Havana Bay and its pilot, Norberto Collado Abreu, got the job of guarding and preserving the cabin cruiser. Since 1976, the “Granma” is on permanent display in a glass enclosure at the Granma Memorial adjacent to the Museum of the Revolution in Havana.

The location of the Granma landing, Playa Las Coloradas, was declared “Granma National Park,” a World Heritage Site by UNESCO, for its natural habitat.

Read another story from us: CIA attempted to assassinate Fidel Castro on 638 occasions

On 2nd December, when Cuba celebrates the “Day of the Cuban Armed Forces,” a replica of the vessel has been paraded at state functions to commemorate the original revolutionary voyage. Granma is also the official newspaper of the Central Committee of the Cuban Communist Party. As a matter of fact, the name has become an icon of the Cuban communism.

- The New Wheeler 55

- The New Wheeler 38

- Earlier Yachts

- News & Events

The Boat that Kept the Cuban Revolution Afloat

On a windy November evening, a band of rebels huddled anxiously on the banks of Tuxpán River. They were former convicts and future world leaders, Naval officers and weapons smugglers — each willing to risk their life to overthrow a murderous dictator.

Overhead an ominous sky loomed, foreshadowing a harrowing voyage ahead.

Standing between the men and their destiny was a treacherous 1,200 nautical mile journey. And despite stormy seas, poor planning and the infinitesimal odds of overpowering Cuba’s military forces, their ship kept their mission afloat.

That ship was a 58-foot Wheeler warship named Granma.

Granma’s Origins

Howard E. Wheeler Sr. founded The Wheeler Shipyard Corporation in 1910 in Brooklyn, New York, to build high-quality, beautifully designed yachts up to 85 feet in length. By the late 1930s, demand was so high they had to expand their facilities to ramp up production.

Shortly after the United States entered the war in late 1941, the government leased land near the Whitestone Bridge in Queens to the Wheeler shipbuilders. Wheeler immediately switched gears to support America’s defense and began producing a fleet of ships for the Navy, Army and Coast Guard. All pleasure boatbuilding was halted.

Granma was originally designed and commissioned for military use as part of a much larger fleet of ships for the war effort. Her carvel-planked hull was made of long-leaf pine on oak frames designed to accommodate 12 passengers with a cruising speed of 9 knots.

After the war, the military ships built by Wheeler were either sold, scuttled or repurposed for private use.

In 1950, Granma first appeared on U.S. Coast Guard records registered to Baton Rouge businessman Robert Erickson . While on a Gulf cruise, Erickson and his wife fell in love with Tuxpán, Mexico, on the banks of Tuxpán River. They decided to build a vacation home there and slept on their yacht while construction was underway.

One frightening night, the Ericksons awoke in Granma’s cabin to thieves who threatened their lives and took all their valuables. Souring their dream, the Ericksons changed tack and relocated to Mexico City, leaving their beloved boat behind. When a storm rolled through Tuxpán, most likely a direct hit from Tropical Storm Florence in 1954, the story of Granma was almost sunk for good.

Granma’s Unlikely Rebirth

Over a thousand nautical miles away in Cuba, Fidel Castro had instigated an ill-fated armed revolt against the Batista government at the Moncada Army Barracks , which led to a 15-year prison sentence. However, under public pressure, Batista released Castro and his collaborators just two years later, a decision that would come back to haunt him.

Fidel and his brother Raúl fled to Mexico, a hub of anti-Batista activists at the time, including Argentinian Marxist Ernesto “Che” Guevara and Mexican arms dealer Antonio Del Conde . Guevara and Del Conde were the exiles’ closest allies in Mexico City, sharing Fidel’s ideals and arming, hiding, funding, feeding and training his growing rebel band.

While passing through Tuxpán to run errands for the rebels, Del Conde saw a white hull peeking out of the marsh grass on the edge of the river. The ship was clearly wrecked, but the name on the transom was legible: Granma. Del Conde was so captivated by the ship’s beauty, he tracked down the Ericksons in Mexico City. While Granma’s diesels were inundated, her keel was broken and the entire boat was generally a mess after being partially submerged, Del Conde was undeterred in his desire to purchase her. He offered the Ericksons $20,000 — equivalent to more than $220,000 today — to buy a ship requiring significant repairs to ever become seaworthy again.

A Bigger Vision for Granma

Granma became Del Conde’s prized possession. He knew it would take him years to restore the ship to her former glory, but he was committed.

His comrade Fidel was also committed … to plotting a revolution. He fervently believed if he could make it to Cuban shores and survive for 72 hours he would be triumphant in overthrowing Batista. After shooting practice one day, Del Conde went to the river to check on Granma, unaware that Fidel followed him. When he set eyes on the mangled ship, Fidel declared his return to Cuba would be on that very boat.

In an instant, Del Conde’s timeline to restore Granma went from years to weeks. He and his team replaced the keel, planks, generator, lights and wiring. The two diesel engines were sent to a GM factory in Mexico City to be repaired. Del Conde commissioned his armory to fabricate new fuel tanks that maximized the space below deck. Sea trials were conducted to establish fuel burn statistics, but without the tonnage of dozens of men and gear on board, their calculations were merely a stab in the dark.

Sailing into the Storm

November 30, 1956, was the date chosen for an attack against the Cuban military, where allies on the island were expecting Fidel’s amphibious force to lead the fight. Castro knew the journey would take a minimum of five days; yet inexplicably he chose November 25 to depart, ignoring the stormy weather forecast and leaving he and his crew no margin for error.

On the evening of the 25 th , Castro’s band of 140 rebels congregated on the bank of Tuxpán River. This posed the first of many challenges – Granma was designed to carry 12 passengers or up to 25 for short trips. Fidel selected 81 men from the group for the mission, including his brother Raúl, trusted aide Ché Guevara and Norberto Collado , a WWII Naval hero with expert navigation skills and an uncanny resistance to seasickness. They packed onto the ship like sardines, shoulder to shoulder with no life vests, only oranges to eat and the hope that they had enough fuel to get to Cuba.

Under the cover of darkness, they sailed down the river and into the Gulf of Mexico where furious seas and 30-knot wind gusts greeted them with impunity.

Tumultuous waters lifted Granma and threw her from cresting waves so hard that the men feared she would sink beneath their feet. The seasick passengers were packed in so tightly they had no choice but to vomit on one another. With the horrendous stench permeating the ship, things went from bad to worse over the next eight hours. The transmission struggled and the men had to bail water out of the boat after the bilge pump failed and Granma took on dangerous amounts of seawater.

For days, Granma’s heavy load struggled against the waves, wind and current. At the helm, Collado slowed her speed to just 6.7 knots, further delaying the crew’s anticipated arrival time.

Ironically, overloading the ship actually made Granma more stable. The weight provided resistance against the roiling seas, without which she would have likely overturned.

Finally, on the third day, the frontal system passed and gave way to mellower seas and sunny skies. After some engine tinkering and winds that calmed to manageable trade winds of 20 knots, Collado revved up Granma to 7.5 knots and steered her toward Cuba.

Making Landfall

Against all odds, Granma’s sturdy construction had delivered them to this point. But their luck was about to run out.

None of the passengers had anticipated such an arduous journey, and misfortune continued to follow them onto land. Guided by the Cape Cruz light, Granma reached Cuba three days behind schedule and not at Castro’s intended rendezvous point with his allies.

Their nautical charts for the coast had been wrong. Their fuel was low. Dawn was approaching. And unbeknownst to them, Batista had caught wind of their surprise attack.

Fearful of being discovered by enemy air patrols, Castro ordered Collado to run Granma aground at full throttle about 100 yards from mangroves. More shipwreck than amphibious assault, the woozy sailors quickly began loading mortars and machine guns into a dinghy, which promptly sank. They had no choice but to lower themselves into chest-deep water and carry their rifles over their heads into the swamp.

The rebels marched through the mangrove forest, but just three days later, their guide betrayed them by leading them straight into an ambush by government troops.

Nearly all of Fidel’s men were killed or captured. A few lucky souls eluded either fate: the Castro brothers, Ché Guevara and about a dozen other men managed to reach the safety of the Sierra Maestra mountains.

The Aftermath

While the initial coup did not go as planned, Fidel and a handful of his comrades lived to fight another day . They rallied a force of about 300 insurgents who took up arms in a succession of victories against government forces. As Fidel’s forces swarmed to nearly 1,000 men, Batista fled to the Dominican Republic in January of 1959. With the previous dictator gone, Fidel’s revolutionary army seized the capital and put him into power for the next five decades.

Granma Today

Norberto Collado was one of the captured rebels during the unsuccessful coup. His comrades freed him from prison in 1959 and he returned to military service. He rose to the rank of captain, and one of his duties was being the caretaker for their beloved Granma.

The Erickson’s former house in Tuxpán was turned into The Mexico-Cuba Friendship Museum , where Granma’s important role in the Cuban Revolution is on full display. You can find Granma restored to pristine condition in a glass-structure behind the Museum of the Revolution in Havana .

Comments are closed.

Sign up to the newsletter to get the latest updates. One-click subscription.

- The Wheeler Story

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Castro’s legacy: how the revolutionary inspired and appalled the world

The man who led a revolution and strode the world stage for half a century left Cuba with free healthcare, food shortages – and not a single street in his name

No street bears his name and there is not a single statue in his honour but Fidel Castro did not want or need that type of recognition. From tip to tip, he made Cuba his living, breathing creation.

Children in red neckerchiefs scampering to free schools, families rationing toilet paper in dilapidated houses, pensioners enjoying free medical treatment, newspapers filled with monotonous state propaganda: all in some way bear the stamp of one man.

Historians will debate Castro’s legacy for decades to come but his revolution’s accomplishments and failures are on open display in today’s Cuba, which – even with the reforms of recent years – still bears the stamp of half a century of “Fidelismo”.

The “maximum leader” was a workaholic micro-manager who turned the Caribbean island into an economic, political and social laboratory that has simultaneously intrigued, appalled and inspired the world.

“When Fidel took power in 1959 few would have predicted that he would be able to so completely transform Cuban society, upend US priorities in Latin America and create a following of global proportions,” said Dan Erikson, an analyst at the Inter-American Dialogue thinktank and author of The Cuba Wars .

The most apparent downside of his legacy is material scarcity. For ordinary Cubans things tend to be either in short supply, such as transport, housing and food, or prohibitively expensive, such as soap, books and clothes.

These problems have persisted since Fidel handed the presidency to his brother Raúl in 2008 . Despite overtures to the United States and encouragement of micro businesses since then, the state still controls the lion’s share of the economy and pays an average monthly wage of less than £15. This has forced many to hustle extra income however they can, including prostitution and low-level corruption. The lucky ones earn hard currency through tourism jobs or receive dollars from relatives in Florida.

Cubans are canny improvisers and can live with dignity on a shoestring, but they yearn for conditions to ease. “We want to buy good stuff, nice stuff, like you do in your countries,” said Miguel, 20, gazing wistfully at Adidas runners on a store on Neptuno street.

Castro blamed the hardship on the US embargo, a longstanding, vindictive stranglehold which cost the economy billions. However, most analysts and many Cubans say botched central planning and stifling controls were even more ruinous. “They pretend to pay us and we pretend to work,” goes the old joke.

Thanks to universal and free education and healthcare, however, Cuba boasts first-world levels of literacy and life expectancy. The comandante made sure the state reached the poorest, a commitment denied to many slum-dwellers across Latin America.

Idealism sparkles in places such as Havana’s institute for the blind where Lisbet, a young doctor, works marathon shifts. “We see every single one of the patients. It’s our job and how we contribute to the revolution and humankind.”

Castro continued to hold a place in people’s hearts and minds despite largely withdrawing from public life in the last decade of his life. Increasingly infirm, he mostly tended his garden in Zone Zero (the high security district of Havana), rebutted frequent premature rumours of his death with photographs showing him holding the latest edition of the state-run newspaper Granma, and wrote the occasional column, including grumpy criticism of Cuba’s drift towards market economics and reconciliation with the United States .

But his influence was clearly on the wane. Although he met Pope Francis in 2015 , he spent a lot more time with his plants than with national and global power brokers. Even before his death, he had become more of a historical than a political figure.

“Fidel was the dominant figure for decades, but Raúl has been calling the shots,” observed a European diplomat based in Havana, who predicted the death would have more symbolic than political significance. “Has his presence been a block to reforms? Possibly. There could be an impact on young Cubans, but we won’t see a huge shift of Cuban politics after Fidel’s death. More significant would be if Raúl dies because he put his leadership on the line for reform.”

Cuba had already begun the move away from Fidel’s era in a similar series of gradual steps to that taken in China after the the death of Mao Zedong or Vietnam after the demise of Ho Chi Minh.

Under the Economic Modernisation Plan of 2010, the state shed 1m jobs, and opened opportunities for small private business, such as paladares – family-run restaurants – and casas particulares , or home hotels. Farmers have been given more autonomy and price incentives to produce more food. The government has eased overseas travel restrictions , loosened pay ceilings, ended controls on car sales and tied up with overseas partners to build a new free-trade zone at the former submarine base in Mariel. The biggest changes have been in the diplomatic sphere, where Cuba strengthened ties with the Vatican and signed a historic accord with the United States to ease half a century of cold war tension .

But this is still an island shaped more by Fidel Castro than any other man. Wander up the marble steps at the centre of Revolution Square and stand where Castro used to give his marathon orations to an audience of more than a million and you can still see just how much the revolution he led reshaped the country. On one side are the giant profiles – illuminated at night – of his two lieutenants: Che Guevara on the ministry of the interior and Camilo Cienfuegos across the facade of the communications ministry.

In the distance, you can see the tower blocks that were formerly the headquarters of major US corporations such as ITT and General Electric but were nationalised under Castro, and hotels such as the Havana Libre, which were once owned by US mobsters but later turned over to the state.

Part of Cuba’s charm for tourists – and the curse for many locals – is that it is all too easy to remember what life here was like in the early days of the revolution because the city has barely move on in the subsequent half century. Thanks to the economic embargo imposed by the United States, Castro’s Cuba became a time capsule. Despite a partial facelift ahead of Pope Francis’s visit in 2015, many streets are still lined by crumbling colonial facades and potted by holes that look like they have been there for decades.

The former mafia hotels have had little more than a lick of paint since they were frequented by mobsters like Meyer Lansky and Charles “Lucky” Luciano. And, of course, classic cars from the 1950s – Buicks, Chryslers, Oldsmobiles and Chevrolets – still cruise the Malecón .

Close to Revolution Square is the run-down La Timba neighbourhood, where a young Fidel Castro cut his teeth as a lawyer defending the local community of shanty-home dwellers against eviction by developers. Juvelio Chinea, an elderly resident, said the changes brought by the revolution in his own life had been modest, but his sons and grandsons had been able to attend university – the first generations in their family to be able to do so.

Chinea recalls hearing the comandante ’s speeches from inside his home. The 21-gun salute used to crack the walls and shake the cutlery. There would be singing and shouting from the crowd, then a hush as Castro started speaking. “Some speeches were better than others,” he remembers. “I wish he could have stayed in power longer.”

Not everyone is so sure about that. At the law department in Havana University, where Castro studied from 1945, there is admiration for the country’s former leader, but many believe he held back development.

“The best thing Fidel did for Cuba was to give us free healthcare at the level of a first world nation,” said one student. “The worst thing is that economic change has been delayed. If Fidel and Raúl had acted earlier, many of today’s problems would already have been solved.”

The student dreams of starting his own private law firm but that is not yet possible, he says, “because the government prefers to keep lawyers and courts under control” so he is thinking of joining his brother, who moved recently to the United States. Nonetheless, he is proud of his country’s and his university’s history. “It’s great that this school was where an icon like Fidel studied.”

That many still feel affection for “ El Jefe Máximo ” despite his ruinous economic policies is because he is judged more for his nationalist triumphs than his communist failures. Castro’s main inspiration was not Karl Marx, but José Martí, the 19th-century Cuban independence hero. While the latter fought to eject Spanish colonisers, Castro ended US neo-imperialist rule by kicking out US corporations and gangsters. The former banana republic is now proudly sovereign.

Camilo Guevara, the son of Castro’s comrade-in-arms Ernesto “Che” Guevara , said these achievements were secure despite the recent overtures from Washington.

“The revolutionaries changed the status quo and established a base for this nation that is independent, sovereign, progressive and economically sustainable. That’s how we got where we are,” he said at the Che Guevara Institute, which is dedicated to maintaining the ideological legacy of his father’s generation.

The message is driven home at the Museum of the Revolution, where the trophies of the early Castro era are prominently displayed outside the building that was once the presidential palace. Here you find the Granma yacht, on which Castro and 81 fellow revolutionaries sailed from Mexico in 1956 to begin the war against the US-backed dictatorship of Fulgencio Batista . Here too is the engine of the US U-2 spy plane that was shot down in 1962 during the Cuban missile crisis . Inside, the exhibits and photographs ram home how this small island, under Castro’s leadership, defied the Yankee superpower despite the threat of nuclear annihilation.

For many elderly Cubans, that was a terrifying, thrilling time to be alive and they remain grateful to Castro for guiding them through it. Frank López, a retired teacher, speaks fondly of that early era under the comandante . “It was frightening. The US jets would fly low and fast above the city, shattering the windows with their noise. We were all trained to use rifles and machine guns and would have to do drills every night. But in the end, nothing happened and we all went back to school. People should stand up to the US more often.”

But he is not dewy-eyed about Castro. Although he admires the early healthcare and education reforms, he also recalls the economic hardships and the intrusive, suspicious state security apparatus. At one point, he was placed under surveillance for six years because a friend had plotted against Castro. These days, a bigger problem is making ends meet in the face of shortages of basic foodstuffs. “We must all do other work to get by. It’s been like that for more than 20 years,” he says. “So while we say thank you to the revolution for the education and healthcare, we also ask how much longer we have to keep saying thank you.”

While Castro became a figurehead for revolutionary armed struggle throughout and beyond Latin America, the former guerrilla was far from universally popular in his home country once he turned his hand to government. Property appropriations, restrictions on religion and crackdowns on suspected enemies left many, particularly in the old middle class, hating him – a sentiment that has spanned the generations.

As a child, Antonio Rodiles said he rebelled after learning his mother’s property had been confiscated and a cousin executed as a suspected CIA agent. “They used to tell me ‘Fidel is your daddy’. I replied ‘No, he’s not’. I hated them for forcing me to do things. As I grew up I realised this kind of system is not natural,” he recalls. Today, he heads the opposition group Citizen Demand for Another Cuba and is often arrested and beaten. “Fidel has left a shadow over Cuba. His legacy is terrible. He destroyed families, individuals and the structure of society.”

Similarly, Rosa María Payá grew up watching her father fight against and suffer from a system that tolerated little dissent. Oswaldo Payá was a leading campaigner for free elections who was imprisoned first for his religious beliefs and then for his political campaigns. He died in a car accident in 2014. Rosa María believes he was forced off the road by the government agents who were following him. She said the Castros have left a legacy of tyranny that is unchanged despite the cosmetic reforms and diplomatic deals of recent years.

“The Cuban people haven’t had a choice since the 1950s,” she says. “My father spent three years in a forced labour camp because he was Catholic. Others were imprisoned with him because they were homosexuals or dressed the ‘wrong’ way. The reality is that you can’t be alternative to the line of Fidel and Raúl.”

From the 1960s onwards, the Intelligence Directorate intrusively monitored opponents, many of whom were beaten by police or spent years in jail. Despite the release of dozens of political prisoners in the wake of the 2014 Cuba-US agreement, many activists were detained or harassed ahead of visits by Barack Obama in 2016 and Pope Francis the previous year.

Yet, compared with the past, there is a little more scope for criticism, a lot more opportunity to travel, and slightly less of a sense of crisis. Cuba may still be more closely aligned to Venezuela than the United States, but it is clearly hedging its bets more than it used to do under Fidel. Today the country is different from the one that confidently erected a now-fading plaque on Avenida Salvador Allende with a quotation from Chile’s socialist leader: “To be young and not to be revolutionary is a contradiction, almost a biological one.”

Instead, on Avenida G, a bohemian hub of cafes and street corners for Havana’s teens, the talk is not of politics but iPods, fashion, films and Major League Baseball.

In a valedictory speech at the close of the 2016 Cuban Communist party congress, Castro urged his compatriots to stick to their socialist ideals despite the warming of ties with the US, but he recognised that his generation was passing.

“Soon I’ll be like all the others,” he said of his dead comrades. “The time will come for all of us, but the ideas of the Cuban communists will remain as proof on this planet that if they are worked at with fervour and dignity, they can produce the material and cultural goods that human beings need, and we need to fight without truce to obtain them.”

Despite the trembling voice and mournful tone, it was a typically combative call to arms. The last of many. It may have been several years since Castro’s thunderous, marathon orations, but Cuba will still feel strangely quiet without him.

- Fidel Castro

Fidel Castro: mass rallies set for Havana and Santiago as ashes journey across Cuba

Fidel Castro obituary

Havana in mourning: 'We Cubans are Fidelista even if we are not communist'

Castro was ‘champion of social justice’ despite flaws, says Corbyn

Fidel Castro, Cuba’s revolutionary leader, dies aged 90

'A towering figure': world leaders past and present react to death of Castro

Trump and Obama offer divergent responses to death of Fidel Castro

Divide and rule: Castro family torn by dysfunction and disagreements

Close but no cigar: how America failed to kill Fidel Castro

Most viewed.

Fidel Castro and the revolution that (almost) wasn’t

Professor of Modern History, University of Leeds

Disclosure statement

Simon Hall does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

University of Leeds provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation UK.

View all partners

Sixty years ago, Fidel Castro launched an audacious bid to liberate Cuba from the dictatorship of Fulgencio Batista – the American-backed strongman whose repressive regime was characterised by corruption and economic and social inequality. At the time, though, this effort appeared destined to be little more than a footnote in the history of the 20th century.

In the early hours of Sunday November 25, the Granma , a creaking, twin-engine leisure yacht left Tuxpan, in Mexico, headed for Cuba. At 58 feet long, and with just four small cabins, the Granma was designed to accommodate about two dozen people. Packed aboard that night, however, were 82 men, all members of the 26th of July Movement , a vanguard organisation committed to ending the rule of Cuban dictator Fulgencio Batista.

Their leader was Fidel Castro, an enigmatic 30-year-old lawyer and professional revolutionary. Squeezed in among the compañeros (who counted Fidel’s younger brother, Raúl , and a young Argentine doctor, Ernesto “Che” Guevara among their number) was a substantial arsenal including two anti-tank guns, a small quantity of food and medical supplies, and 2,000 gallons of fuel stored in metal cans on deck.

A combination of rough seas and the poor state of the Granma itself soon threatened total disaster. Almost the entire crew was afflicted by dreadful seasickness and the boat came perilously close to sinking when the bilge pumps failed. Fidel had originally planned to land at Niquero , on the south-east of the island, on November 30 to coincide with a planned uprising in the nearby city of Santiago de Cuba . But the boat’s badly worn gears meant that the journey itself was painfully slow – and they were still at sea when the city rose up without them . The rebellion, however, was brutally crushed after a couple of days.

The Granma eventually hit the Cuban coast as dawn began to break on December 2. Rather than landing at Niquero , where allies were waiting with supplies and trucks, the Granma ran aground ten miles south of the agreed rendezvous. They could hardly have picked a worse spot.

It was ‘hell’

Forced to abandon most of their equipment, the compañeros – proudly wearing their new drab-olive fatigues and boots and carrying rifles and knapsacks – waded ashore through muddy salt water, only to find themselves faced with seemingly endless mangrove swamps, whose thick mass of roots proved nearly impossible to penetrate. In the words of Raúl Castro, it was “ hell ”. They struggled on for several hours before finally reaching dry land, exhausted and hungry, and caked in mud.

The rebels’ only hope now was to reach the relative sanctuary of the Sierra Maestra mountains to the east. But by the morning of December 5, malnourished, desperately thirsty and suffering from fungal infections and painful open blisters, they were, as Che Guevara later recalled, “ an army of shadows, ghosts ”.

There was no choice but to stop. They had reached Alegría de Pío (meaning “Joy of the Pious”), a grove of trees that bordered a sugarcane field on one side. Most of the men stretched out, and slept.

Later that afternoon Che was leaning against a tree, munching on a couple of crackers, when the first shot rang out. Betrayed by a guide, who had left the camp earlier in the day, the compañeros were under attack from Batista’s troops . As fighter jets swooped low over the woods an infantry unit opened fire. In the confusion, several revolutionaries were killed; others scrabbled desperately for cover. Wounded in the neck, Guevera returned fire with his rifle, before dragging himself into the relative safety of an adjoining field. Ten days after leaving Mexico, Castro’s “army” had been routed.

Suicide mission

In mid-December 1956, nobody – with the possible exception of Fidel Castro – thought that the little band of rebels would prove victorious. Indeed, Castro’s attempt to launch a revolution was widely dismissed by journalists as “ quixotic ”, “ pathetic ” and even “ suicidal ”.

Rumours abounded that Castro had been killed. The respected news bureau, United Press International, as well as the New York Times, reported his death, and that of his brother Raúl, as “fact” . Having noted Castro’s arrival in Cuba in its leader column on December 4, The Times of London confidently swatted aside its significance. Noting that Batista was a “veteran of many revolutions”, it predicted that : “it is unlikely that the latest will shake his position”.

With many of the Granma’s landing party either killed or captured, and the remaining 20 or so survivors scattered, their prospects in early December certainly looked pretty bleak. For several days Castro himself commanded the grand total of two men (Universo Sánchez, a peasant who served as Fidel’s bodyguard, and Faustino Pérez, a pharmacist). Slowly, though, the rebels began to regroup in the foothills of the Sierra Maestra, nearing Mt. Caracas, 4,000 feet above sea level, by year’s end.

It was from here that Castro launched a remarkable military campaign, which – with the support of the urban-based opposition , the labour movement and others – culminated in his triumphant march into Havana on January 8, 1959, following Batista’s flight nine days earlier , on New Year’s Eve.

The Cuban revolution would reverberate far beyond the Caribbean, and not just because for 13 days in October 1962 the world teetered on the brink of nuclear annihilation. Revolutionary Cuba, under Castro’s leadership, helped to promote socialism throughout Latin America and also played a major role in the global struggles against imperialism, racism, and capitalism .

Castro provided military support to leftist revolutionaries in Algeria and Angola, and sent tens of thousands of Cuban health workers and physicians to the third world. In the late 1950s and early 1960s many black Americans, too, were inspired by Castro’s commitment to racial equality. During a visit to New York in September 1960 to address the UN General Assembly, Castro, enraged by demands that his delegation pay their bill upfront, and in cash, famously stormed out of the Shelburne Hotel in Manhattan’s Midtown and took up residence at the Hotel Theresa, in the heart of Harlem .

There, he was afforded a rapturous reception by the black population, and entertained a slew of world leaders – including Nikita Khrushchev, Gamal Abdel Nasser and Jawaharlal Nehru. A bitter critic of apartheid, Castro also provided consistent support to the ANC .

Although its lustre would eventually fade, not least because of Castro’s dreadful human rights record , the Cuban revolution also re-energised leftist movements across Europe and in the United States – many of which had struggled to find their moorings in the aftermath of Khrushchev’s denunciation of Stalin and the Soviet invasion of Hungary . Castro, and – above all – Che Guevara, became revolutionary icons for a generation of sixties radicals .

In 1956 , Castro’s bold claim that: “ we will be free or we will be martyrs ” resonated with the times. The year also saw African American activists in Montgomery, Alabama, achieve a historic victory following their year-long boycott of the city’s segregated buses, tens of thousands of South African women take to the streets of Pretoria to denounce apartheid, independence for the Sudan, Tunisia, Morocco and the Gold Coast (Ghana), and a popular uprising against Stalinist rule in Hungary.

Sixty years on, however, Castro’s death serves as a coda to a year in which the forces of history appear to be marching to a very different beat.

- Raul Castro

- Fidel Castro

- Che Guevara

- Cuban revolution

School of Social Sciences – Public Policy and International Relations opportunities

Deputy Editor - Technology

Sydney Horizon Educators (Identified)

Project Officer, Fellowship Experience

Deputy Vice-Chancellor (Academic and Student Life)

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Cuban Revolution

By: History.com Editors

Updated: August 9, 2023 | Original: August 19, 2021

The Cuban Revolution was an armed uprising led by Fidel Castro that eventually toppled the brutal dictatorship of Fulgencio Batista. The revolution began with a failed assault on Cuban military barracks on July 26, 1953, but by the end of 1958, the guerrilla revolutionaries in Castro’s 26th of July Movement had gained the upper hand in Cuba, forcing Batista to flee the island on January 1, 1959.

Lead-Up to the Cuban Revolution

After the Spanish-American War , the U.S. military directly administered the island until 1902, when Cuba became a republic, with sugar as its main commercial export. After a financial crisis and persistent governmental corruption, Gerardo Machado was elected as Cuba’s president in 1925, pledging reform. Instead, Machado became Cuba’s first dictatorial ruler, until he was ousted in 1933 after a revolt led by Fulgencio Batista, a rising star in the Cuban military.

Various presidents came and went over the next two decades, but Batista remained a constant force. He served as president himself from 1940-44, and ran for a second term in 1952. Facing defeat, he overthrew the government in a bloodless coup and canceled the elections.

Fidel Castro and the 26th of July Movement

Castro, a young lawyer and activist, had been running for Congress as part of the Cuban People’s Party before Batista seized power. Seeking to arm a revolutionary opposition to the Batista regime, he led a raid against the Moncada army barracks in the city of Santiago de Cuba on July 26, 1953. Most of the group was killed; Castro and his younger brother, Raúl, escaped but were later arrested and imprisoned.

Fidel Castro’s trial and imprisonment served to build his reputation as a revolutionary leader. After Batista yielded to international pressure and granted amnesty to many political prisoners in 1955, Castro headed to Mexico, where he began organizing Cuban exiles into a movement named for the date of the failed Moncada attack.

The Cuban Revolution Begins

In November 1956, 82 men representing the 26th of July Movement sailed from Mexico aboard the Granma, a small yacht. Batista’s forces learned of the attack ahead of time, and ambushed the revolutionaries shortly after they landed in a remote area of eastern Cuba on December 2, 1956. Though most of the group was killed, around 20 of them escaped, including Fidel and Raúl Castro and one of Castro’s foreign recruits, Argentine-born doctor Ernesto “Che” Guevara .

Reaching the Sierra Maestra mountains, Castro’s group attracted new members and began a guerrilla campaign against Batista’s better-armed and more numerous forces. Over the next two years, Cuba existed in a virtual state of civil war, with rebel forces carrying out attacks on government facilities, sugar plantations and other sites as Batista’s regime cracked down on anyone suspected of collaborating with Castro’s revolution.

Rebels Seize the Advantage

In response to growing opposition, Batista suspended constitutional protections for Cubans, including freedom of speech and assembly. The following year, he called for the planned presidential election to be postponed, blaming the ongoing violence.

Believing support for the revolution was waning, Batista called for a major military offensive against the rebels in the Sierra Maestra mountains in the summer of 1958. Instead, the rebels swiftly turned back the offensive, forcing the army to withdraw. With international media giving favorable press coverage to the revolutionaries, the United States began to withdraw support for Batista’s government, which it had previously backed due to the dictator’s anti-communist stance.

Castro's Revolution Triumphs

In November 1958, the Cuban presidential election went ahead amid widespread fraud, with Batista’s chosen successor winning despite a more moderate candidate receiving more legitimate votes. As support for Batista continued to erode, the 26th of July revolutionaries struck the decisive blow in late December 1958, with Guevara’s forces defeating a much larger army garrison in the Battle of Santa Clara and capturing a train loaded with vital arms and ammunition.

On January 1, 1959, with rebel forces bearing down on Havana, Batista fled Cuba for the Dominican Republic; he later proceeded to Portugal, where he would remain in exile until his death in 1973.

Fidel Castro arrived in Havana on January 9 to take charge of a new provisional government, quickly consolidating control and rounding up Batista’s supporters, many of whom were tried and executed by revolutionary courts. Though Castro had called for elections during the revolution, he postponed them indefinitely once he came to power.

U.S.-Cuba Relations Break Down

The United States was one of the first countries to recognize Castro’s government in Cuba, but relations between the two countries quickly deteriorated as Castro implemented a communist regime and forged close ties with the Soviet Union, the U.S. enemy in the Cold War . The United States broke off diplomatic relations with Cuba in early 1961, and the next few years were marked by escalating tensions, including the Bay of Pigs invasion (April 1961) and the Cuban missile crisis (October 1962).

Despite a long-running U.S. trade embargo, widespread economic hardship, a mass exodus of hundreds of thousands of Cubans and multiple efforts to implement regime change, Fidel Castro remained in power until 2008, when he formally resigned after handing off power to his brother . He died in 2016.

“Cuba Marks 50 Years Since 'Triumphant Revolution'.” NPR , January 1, 2009. Neil Faulkner, “The Cuban Revolution.” Military History Matters , January 10, 2019. Cuban Revolution. Encyclopedia Britannica . Tony Perrottet, Cuba Libre! Che, Fidel, and the Improbable Revolution That Changed World History (Blue Rider Press, 2019)

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

- Submissions

Cuba’s Granma Yacht: 65 Years since its Historic Voyage

By Alejandra Garcia on December 2, 2021

photo: Juvenal Balán

On December 2, 1956, the Granma yacht arrived in Cuba at Las Coloradas beach, in the eastern part of the island, after a seven-day voyage that began in Mexican waters. On more than one occasion during the trip, the 82 Cuban expedition members, led by Fidel Castro, believed that the small ship would not reach its final destination.

On November 25 of that year, the small wooden yacht, built-in 1943, set sail down the Tuxpan River towards the Gulf of Mexico. It was close to two o’clock in the morning, and barely a soul could be seen. It sailed with its lights off and in absolute silence to avoid the attention of the Mexican guards. The darkness and the sacks of oranges that were placed on the bow did not let them see the course of the boat, and they almost took a detour, which would have taken them away from the open sea.

Fortunately, the revolutionaries corrected the route, and the Granma yacht advanced through the wide Tuxpan river with the expeditionaries piled almost on top of each other. Raúl Castro, brother of the Cuban leader, wrote down every detail of those first hours aboard the Granma: “We left at full speed while we saw just a few lights of the city of Tuxpan”.

Historian Heberto Norman Acosta added other little-known details in an article published recently in Cubadebate: “When the ship was far enough away from Mexico’s mainland, the lights were turned on, and the 82 expedition members excitedly sang the National Anthem. How happy Fidel and the rest of the expedition members must have been when they saw themselves already on their way to Cuba.”

The first days of the journey were the most difficult ones. The Argentine doctor Ernesto (Che) Guevara, in his “Pasajes de la Guerra” (Passages of the war), related what happened onboard the yacht once it reached the turbulent waters of the gulf.

“The instability of the waters made most of the crew sick. The whole ship looked ridiculously tragic: men with anguish on their faces, clutching their stomachs. Some had their heads stuck in a bucket, and others were lying in the strangest positions, immobile and with their clothes soiled by vomit. Except for two or three sailors and four or five others, the rest of the eighty-two crewmen were seasick,” he described.

While this was happening, the lower cabins began to fill with water due to a malfunction in the vessel. Raul wrote in his diary: “The yacht was about to sink, as it was taking on a lot of water and the turbine was unable to drain it. We were bailing it out with buckets. The helmsman told Fidel that we had to go ashore. Fidel said we had to continue even though we were sinking. The swells were higher than the ship.”

Years later, Fidel recalled those hours of despair, “We were not going to stop because of a storm nor by the risk of sinking. Nothing would hold us back or turn our course away from Cuba. We could sink on the way. But we were not going to turn back.”

After a frantic hours-long battle, they noticed that the water had begun to recede little by little because humidity expanded the wood and allowed the water to stop coming in.

The last of the challenges they had to face was the moment when a man fell into the water, just as they were sighting Cuban land from the southern waters of the Caribbean Sea.

At the cry of “Man overboard!” Fidel gave orders to stop the stop the course and maneuver to rescue the comrade. One of the expedition members, Pedro Sotto Alba, wrote in his diary: “At about one o’clock in the morning, Roque was holding on to the yacht’s antenna, and in a moment of swell he fell into the sea, antenna and all. No matter how fast he got afloat, he was already far away”.

The boat didn’t go anywhere until their comrade was rescued. It was about three-quarters of an hour of going in circles trying to find him. They managed to scan him through the choppy waves by the faint light of a flashlight.

Shortly after the rescue, the disembarkation would begin, which happened two days later than planned. The arrival of the 82 revolutionaries on the eastern side of Cuba changed the course of the island forever. That December 2, the words Fidel said shortly before setting sail on that small yacht full of men from a dock in Tuxpan were fulfilled: “If I leave Mexico, I will arrive in Cuba; If I arrive, I’ll enter; If I enter, I’ll triumph.” And so he did.

Source: Resumen Latinoamericano – English

Subscribe to Resumen

Email address:

First Name:

Archives by Year

Archives by month.

Landing of the Granma

Granma is a yacht that was used to transport 82 fighters of the Cuban Revolution from Mexico to Cuba in November 1956 to overthrow the regime of Fulgencio Batista . The 60-foot (18 m) diesel-powered vessel was built in 1943 by Wheeler Shipbuilding of Brooklyn, New York, as a light armored target practice boat, US Navy C-1994, and modified postwar to accommodate 12 people. "Granma", in English, is an affectionate term for a grandmother; the yacht is said to have been named for the previous owner's grandmother.

Exile of Moncada attackers

In 1953, beginning their first attack against the Batista government, Fidel Castro gathered 160 fighters and planned a multi-pronged attack on two military installations. On 26 July 1953, the rebels attacked the Moncada Barracks in Santiago and the barracks in Bayamo , only to be defeated decisively by the far more numerous government soldiers. It was hoped that the staged attack would initiate a nationwide revolt against Batista's government. After an hour of fighting most of the rebels and their commander fled to the mountains. The exact number of rebels killed in the battle is debatable; however, in his autobiography, Fidel Castro wrote that six were killed during the fighting, and an additional 55 were executed after being captured by the Batista government. Due to the government's large number of men, Hunt revised the number to about 60 members taking the opportunity to flee to the mountains along with Castro. Among the dead was Abel Santamaría , Castro's second-in-command, who was imprisoned, tortured, and executed on the same day as the attack.

Numerous important revolutionaries, including the Castro brothers, were captured soon afterwards. During a political trial, Fidel spoke for nearly four hours in his defense, ending with the words "Condemn me, it does not matter. History will absolve me ." Castro's defense was based on nationalism, representation and beneficial programs for the non-elite Cubans, justice for the Cuban community, and his patriotism. Fidel was sentenced to 15 years in the prison Presidio Modelo , located on Isla de Pinos , while Raúl was sentenced to 13 years. However, in 1955, yielding to political considerations, the Batista government freed all political prisoners in Cuba, including the Moncada attackers. Fidel's Jesuit childhood teachers succeeded in persuading Batista to include Fidel and Raúl in the release. Fidel Castro left Cuba for exile in Mexico.

In Mexico, Fidel Castro soon met with Spanish Civil War veteran Alberto Bayo . Castro informed Bayo he had a plan to invade Cuba but had no money for weapons or a single volunteered soldier. Despite the lack of resources Bayo decided to assist Castro's plan because giving military advice would not cost him anything. With time Fidel would be joined by his brother Raul Castro , and his old comrade Antonio "Ñico" López. Lopez would bring Raul Castro to a nearby hospital where an exiled Che Guevara was working as a doctor. Guevara, who had met Lopez previously in Guatemala was invited to meet with Fidel Castro by Lopez. The Castro brothers, Lopez, and Guevara were to be the first volunteers for the expedition. On the evening of July 8, 1954 Guevara and Fidel Castro met in the home of Maria Antonia Gonzalez. The apartment later became a headquarters for the rebels. Castro realised he had little money for his plans and in October travelled to New Jersey and Miami to raise money from Cuban exiles for his invasion.

Preparations

The yacht was purchased on October 10, 1956, for MX$ 50,000 ( US$ 4,000 in 1956) from the United States-based Schuylkill Products Company, Inc., by a Mexican citizen—said to be Mexico City gun dealer Antonio "The Friend" del Conde—secretly representing Fidel Castro . The builder, Wheeler Shipbuiding, then of Brooklyn, New York, now of Chapel Hill, North Carolina, also built Ernest Hemmingway 's boat Pilar . It is still unknown who removed the light armor and expanded the cabin postwar to convert the navy training boat into a civilian yacht. Castro's 26th of July Movement had attempted to purchase a Catalina flying boat maritime aircraft, or a US naval crash rescue boat for the purpose of crossing the Gulf of Mexico to Cuba, but their efforts had been thwarted by lack of funds. The money to purchase Granma had been raised in the US state of Florida by former President of Cuba Carlos Prío Socarrás and Teresa Casuso Morín .

Soon after midnight on November 25, 1956, in the Mexican port of Tuxpan, Veracruz , Granma was boarded surreptitiously by 82 members of the 26th of July Movement including their commander, Fidel Castro, his brother, Raúl Castro , Che Guevara , and Camilo Cienfuegos . The group—who later came to be known collectively as los expedicionarios del yate Granma (the Granma yacht expeditioners)—then set out from Tuxpan at 2 a.m. After a series of vicissitudes and misadventures, including diminishing supplies, sea-sickness, and the near-foundering of their heavily laden and leaking craft, they disembarked on December 2 on the Playa Las Coloradas , in the municipality of Niquero , in modern Granma Province (named for the vessel), formerly part of the larger Oriente Province . Granma was piloted by Norberto Collado Abreu , a World War II Cuban Navy veteran and ally of Castro. The location was chosen to emulate the voyage of national hero José Martí , who had landed in the same region 61 years earlier during the wars of independence from Spanish colonial rule.

Santiago de Cuba uprising

A rebellion organized by the 26th of July movement and planned by Haydée Santamaría , Celia Sánchez , and Frank País occurred in Santiago de Cuba . It was planned in occurrence with the landing of the Granma. The rebellion happened on November 30 but was destroyed quickly by police. The Granma itself wouldn't arrive in Cuba until days later on December 2. It was made two days late due to bad weather during the voyage to Cuba.

Granma landing

We reached solid ground, lost, stumbling along like so many shadows or ghosts marching in response to some obscure psychic impulse. We had been through seven days of constant hunger and sickness during the sea crossing, topped by three still more terrible days on land. Exactly 10 days after our departure from Mexico, during the early morning hours of December 5, following a night-long march interrupted by fainting and frequent rest periods, we reached a spot paradoxically known as Alegría de Pío (Rejoicing of the Pious). – Che Guevara

Batista predicted correctly that the landing would occur, and his troops were ready. Consequentially, the landing party was bombarded by helicopters and airplanes soon after landing. Since the terrain on the coastline provided little cover, the party was an easy target. Many casualties ensued, most of them during battle at Alegría de Pío [ es ] further inland. The survivors continued to the foot of Pico Turquino in the Sierra Maestra to perform guerilla war.

Initially, Batista did not know who exactly were among the casualties, and international media widely reported that Fidel had died. This was, however, not the case. Of the 82, about 21 had survived. According to the most credible version, the survivors were Fidel, Raúl, Guevara, Armando Rodríguez, Faustino Pérez [ es ] , Ramiro Valdés , Universo Sánchez, Efigenio Ameijeiras , René Rodríguez, Camilo Cienfuegos , Juan Almeida Bosque , Calixto García, Calixto Morales, Reinaldo Benítez, Julio Díaz, Luis Crespo Cabrera, [ citation needed ] Rafael Chao, Ciro Redondo [ es ] , José Morán, Carlos Bermúdez, and Fransisco González. All others had been either killed, captured, or left behind.

Granma yacht expeditioners

The 82 expeditioners were:

- Fidel Castro

- Juan Manuel Márquez Rodríguez [ es ]

- Faustino Pérez [ es ]

- José Smith Comas

- Juan Almeida Bosque

- Raúl Castro

- Félix Elmuza

- Armando Huau

- Che Guevara

- Antonio López

- Teniente Jesús Reyes

- Cándido González

- Onelio Pino

- Roberto Roque

- Jesús Montané [ es ]

- Mario Hidalgo

- César Gómez

- Rolando Moya

- Horacio Rodríguez

- José Ponce Díaz

- José Ramón Martínez

- Fernando Sánchez-Amaya

- Arturo Chaumont

- Norberto Collado

- Gino Donè Paro [ it ]

- Evaristo Montes de Oca

- Esteban Sotolongo

- Andrés Luján

- José Fuentes

- Pablo Hurtado

- Emilio Albentosa

- Luis Crespo

- Rafael Chao

- Ernesto Fernández

- Armando Mestre

- Miguel Cabañas

- Eduardo Reyes

- Humberto Lamothe

- Santiago Hirzel

- Enrique Cuélez

- Mario Chanes [ es ]

- Manuel Echevarría

- Fransisco González

- Mario Fuentes

- Noelio Capote

- Raúl Suárez

- Gabriel Gil

- Alfonso Guillén Zelaya

- Miguel Saavedra

- Pedro Sotto

- Arsenio García

- Israel Cabrera

- Carlos Bermúdez

- Antonio Darío López

- Oscar Rodríguez

- Camilo Cienfuegos

- Gilberto García

- Jaime Costa [ es ]

- Norberto Godoy

- Enrique Cámara

- Armando Rodríguez

- Calixto García

- Calixto Morales

- Reinaldo Benítez

- René Rodríguez

- Jesús Gómez

- Francisco Chicola

- Universo Sánchez

- Efigenio Ameijeiras

- Ramiro Valdés

- Arnaldo Pérez

- Ciro Redondo [ es ]

- Rolando Santana

- Ramón Mejias

Soon after the revolutionary forces triumphed on January 1, 1959, the cabin cruiser was transferred to Havana Bay . Norberto Collado Abreu, who had served as main helmsman for the 1956 voyage, received the job of guarding and preserving the yacht. [ citation needed ]

Since 1976, the yacht has been displayed permanently in a glass enclosure at the Memorial Granma adjacent to the Museum of the Revolution in Havana . A portion of old Oriente Province , where the expedition made landfall, was renamed Granma Province in honor of the vessel. UNESCO has declared the Landing of the Granma National Park —established at the location (Playa Las Coloradas)—a World Heritage Site for its natural habitat.

The Cuban government celebrates December 2 as the Day of the Cuban Armed Forces , and a replica has also been paraded at state functions to commemorate the original voyage. In further tribute, the official newspaper of the Central Committee of the Cuban Communist Party has been named Granma . The name of the vessel became a symbol for Cuban communism .

- Cuban exile

- United States embargo against Cuba

- La Coubre explosion

- Bay of Pigs Invasion

- Cuban Missile Crisis

- Escopeteros

- Radio Rebelde

- Robert Maheu

- Awards and honours

- Eponymous things

- Religious views

- Relationship with dairy

- Granma (yacht)

- Motor yachts

- Cuban Revolution

- Museum ships in Cuba

This page was last updated at 2024-03-12 06:17 UTC. Update now . View original page .

All our content comes from Wikipedia and under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License .

If mathematical, chemical, physical and other formulas are not displayed correctly on this page, please use Firefox or Safari

A Brief Introduction to the Museum of the Revolution, Havana, Cuba

The decision to found a museum that told the story of the Cuban Revolution came soon after the 1959 victory against the Batista dictatorship . The horrors of the ousted dictatorship had been so gruesome, and the sacrifice of its opponents had been so heroic, that collecting the evidence and showing it to the world seemed like the logical thing to do.

After moving from building to building following its foundation in December 1959, the museum found its definitive home at the former Presidential Palace in 1974. In its efforts to rebuild the country, the new government had undertaken this sort of eloquent re-purposing of buildings, turning barracks that had been used for torture into elementary schools, and installing daycare centers for working-class families in mansions that had been expropriated from the very wealthy.

The Presidential Palace, which for 40 years had served as the headquarters of the Cuban presidency, was given up to for a museum.

The building

Become a Culture Tripper!

Sign up to our newsletter to save up to 500$ on our unique trips..

See privacy policy .

Originally, it was destined to be the headquarters of the provincial government (that is, the Havana Governor’s Office), but following a visit to the construction site by First Lady Mariana Seva in 1917, arrangements were made for the place to host the president’s office instead.

At its inauguration on January 31, 1920, it was one of the tallest buildings Cuba. The ground floor housed offices and administrative facilities, including a telephone plant, a power plant, and a stable.

The president’s office was on the first floor with the rest of the most important rooms of the building: the Hall of Mirrors (a replica of the one at the Palace of Versailles), the Golden Hall (with walls plated with yellow marble), a chapel, and the Council of Ministers’ central office.

The presidential residence was on the second floor, and the force in charge of the president’s protection, on the top floor.

The dome that tops the building, a nice addition to the original project, is plated with colorful tiles that make it stand out even more when the sun reflects on them.

The inside of the building is of an impressive beauty: a Carrara-marble staircase gives access to the upper floors from the lobby, and the interior decoration, commissioned to New York’s Tiffany Studios, features Cuban-themed motifs, luxury furniture, and works of art by some of the most important Cuban artists of all times, including Armando Garcia Menocal and Leopoldo Romanach.

Located very near Parque Central in Old Havana, more accurately on a large block formed by Refugio, Avenida de las Misiones and Zulueta streets, the Museo de la Revolucion is an important point of reference when trying to understand how Cuba came to be what it is today.

Although the collection includes historic pieces dating back to the early years of the Spanish colonization in the 15th century, the core of the display is the objects linked to Cuba’s struggle to put an end to the dictatorship of Fulgencio Batista in the 1950s.

The rebel movement led by Fidel Castro and other opposition groups were a reaction to the unbearable conditions that the Cuban people had to suffer under the Batista government.

The popular support that the movement received in 1959 was in part a big “thank you” for having put an end to that nightmare.

The objects that were preserved from the war against Batista from 1953 to 1959 tell the story of a dictatorial regime that practiced torture and murder against its opponents, and that was equipped with state of the art weapons, planes, and vehicles.

From tweezers and shackles used to pull the nails of the detainees, to gas torches used to burn their backs as a form of torture, the collection is very graphic and spares no detail.

In fact, at times one may get the feeling that the level of detail is a little overwhelming, and that the exhibit could have been summarized to tell a more general story. However, bear in mind that the museum was originally designed for Cuban visitors, for whom many of the objects may be more interesting, given their more ample background about the events, or even their personal links to the history of the country.

What to see

Although having some knowledge of Cuban history and speaking Spanish may be an advantage, the visit can be as interesting with the help of a guide. Tickets cost CUC$5 (US$5), plus CUC$3 (US$3) for the guide’s services (which you may choose not to use). Bags and backpacks are not allowed, and must be deposited at the entrance.

The second floor is the logical starting point for a visit: it opens with the colonial period (15th century), moving then to the American intervention in the war against Spain (1898), and then to the Republican period (1902–1959), considered by Cuban official historiography as a neo-colonial period due to the control that the U.S. exerted over Cuba’s politics and economy.

The pre-liberation history concludes with the abovementioned extensive display of objects linked to Fidel Castro’s 26 of July Movement : from the first armed actions against the regime in Santiago de Cuba in 1953, the trial that followed for the participants, their imprisonment, amnesty, exile, return to Cuba on board of a yacht from Mexico, and the final war fought in the Sierra Maestra mountains in the eastern part of the country.

Sculptures of Che Guevara and Camilo Cienfuegos —a fellow commander of the Rebel Army—is one of the main attractions, especially for school children who learn about the heroes in school, and then get to see them in their uniforms as if they were still alive in the mountains.

Relevant for this last historic period also is the building itself: in 1957, the Presidential Palace was object of an attack by an anti-dictatorship group, the Revolutionary Directorate (DR), whose goal was to assassinate the dictator in his own house. The attack failed and most of the participants were killed. Bullet holes from those events are still visible in the main stairway at the entrance, and in the outdoor exhibit there’s a red delivery truck used by the attackers as a cover to be able to get close to the building.

The first floor covers the period extending from 1959 onwards, with more emphasis in the early years of social, political and economic transformations. A big highlight is the Bay of Pigs invasion (1961), that the Cuban forces were able to counter in only 3 days. The tank used by Fidel Castro in those events can be seen outside the main entrance.

The back doors of the ground floor lead to another exhibit outside: the Granma Memorial. The central piece here is the Granma Yacht, visible from behind a glass cover. Standing that close to the yacht, it is impressive to think that 82 people fit in the tiny boat in the journey from Yucatan to the eastern part of Cuba (Oriente).

In addition to other large vehicles, the memorial includes a permanent flame burning in tribute to the Eternal Heroes of the Motherland.

KEEN TO EXPLORE THE WORLD?

Connect with like-minded people on our premium trips curated by local insiders and with care for the world

Since you are here, we would like to share our vision for the future of travel - and the direction Culture Trip is moving in.

Culture Trip launched in 2011 with a simple yet passionate mission: to inspire people to go beyond their boundaries and experience what makes a place, its people and its culture special and meaningful — and this is still in our DNA today. We are proud that, for more than a decade, millions like you have trusted our award-winning recommendations by people who deeply understand what makes certain places and communities so special.

Increasingly we believe the world needs more meaningful, real-life connections between curious travellers keen to explore the world in a more responsible way. That is why we have intensively curated a collection of premium small-group trips as an invitation to meet and connect with new, like-minded people for once-in-a-lifetime experiences in three categories: Culture Trips, Rail Trips and Private Trips. Our Trips are suitable for both solo travelers, couples and friends who want to explore the world together.

Culture Trips are deeply immersive 5 to 16 days itineraries, that combine authentic local experiences, exciting activities and 4-5* accommodation to look forward to at the end of each day. Our Rail Trips are our most planet-friendly itineraries that invite you to take the scenic route, relax whilst getting under the skin of a destination. Our Private Trips are fully tailored itineraries, curated by our Travel Experts specifically for you, your friends or your family.

We know that many of you worry about the environmental impact of travel and are looking for ways of expanding horizons in ways that do minimal harm - and may even bring benefits. We are committed to go as far as possible in curating our trips with care for the planet. That is why all of our trips are flightless in destination, fully carbon offset - and we have ambitious plans to be net zero in the very near future.

See & Do

A guide to sailing in and around cuba.

The Best Snorkelling Spots in Cuba

The Most Beautiful Towns To Visit While Sailing in Cuba

Food & Drink

The best cuban desserts to try now.

Slow Burn: How the Meticulous Craft of Cigar Making Put Cuba on the Map

Guides & Tips

Stay curious: experience cuba from your living room.

7 Inspiring Women Who Hail from Cuba

Is Cuban Rum Really the Best in the World?

The Best Cuban Rum Cocktails to Try

The Best Cigars in the World: Alternatives to the Cuban Cigar

Does Fidel Castro Really Have Hundreds of Children?

10 Things You Never Knew about Cuban Cigars

Winter sale offers on our trips, incredible savings.

- Post ID: 1227755

- Sponsored? No

- View Payload

Social network

- Science and Technology

Granma yacht’s sculpture unveiled in Tuxpan

A beautiful sculpture that replicates the Granma yacht was unveiled in Tuxpan, Veracruz, the place from where Fidel Castro and 82 revolutionary combatants departed to begin the guerrilla struggle in Cuba.

Cuban Ambassador to Mexico, Marcos Rodríguez, Veracruz’s Governor Cuitláhuac García Jiménez, Senator Gloria Sánchez, and Tuxpan’s Mayor José Manuel Pozos attended the ceremony on Monday. They also participated in a tribute to the Apostle of Cuban independence, José Martí, who was the mastermind of the attack on the Moncada Garrison.

In his words of gratitude for such an event, Ambassador Rodríguez praised the reproduction of the Granma yacht obtained by Antonio del Conde, known as El Cuate, with great haste and exquisite quality by Cuban sculptors with the support of Mexican workers.