Watch CBS News

Who are the Russian oligarchs the U.S. is targeting with sanctions?

By Allison Elyse Gualtieri

March 7, 2022 / 11:00 AM EST / CBS News

The U.S. Department of the Treasury and the U.S. Department of State sanctioned more than two dozen individual Russians last week, piling on the financial pressure on the elites who have influence with Russian President Vladimir Putin in the wake of Russia's invasion of Ukraine .

"The aid of these individuals, their family members, and other key elites allows President Vladimir Putin to continue to wage the ongoing, unprovoked invasion of Ukraine," according to a release from the Treasury Department on March 3.

"Treasury is committed to holding Russian elites to account for their support of President Putin's war of choice," said Secretary of the Treasury Janet L. Yellen, adding that the move demonstrates "our commitment to impose massive costs on Putin's closest confidants and their family members and freeze their assets in response to the brutal attack on Ukraine."

The U.S. and Western partners and allies have been pointedly sanctioning Russian oligarchs , saying these elites have pillaged the Russian state and used family members to move and conceal assets.

The announcement said the Treasury Department will share financial intelligence and other evidence with the Department of Justice to support criminal prosecutions and seizure of assets.

Here's a look at the wealthy individuals the U.S. singled out for sanctions last week:

Alisher Usmanov

Alisher Usmanov is one of Russia's wealthiest billionaires, whose vast holdings include interests in the metals and mining, telecommunications and information technology sectors both in and outside of Russia.

His super-yacht "Dilbar" — which has two helipads and an indoor pool — is one of the world's largest, worth between $600-$735 million and costs an estimated $60 million a year to operate.

His business jet is believed to have cost between $350 and $500 million and is one of the largest privately owned planes in Russia. The Treasury Department states it was previously leased out for use by Uzbekistan's president.

Treasury pointed to Usmanov's alleged financial ties to Russian President Vladimir Putin as well as former president and prime minister Dmitry Medvedev, now deputy chairman of the Security Council of Russia, who reportedly had use of "luxurious residences" controlled by Usmanov.

The U.K. also announced sanctions and a full asset ban on Usmanov, saying he had "significant interests in English football clubs Arsenal and Everton, owns several properties worth tens of millions of pounds and pegged his worth in excess of $18.4 billion.

Nikolay Petrovich Tokarev

Nikolay Tokarev, whom the Treasury Department called a "long-time Putin associate," is the president of the state-owned Transneft pipeline company, which the department called "one of Russia's most important companies." He's also spent time in the government — first in the 1980s as a KGB agent alongside Putin in Dresden, then in the administrative department of the President of the Russian Federation. His wife, Galina Alekseyevna Tokareva, is also being sanctioned.

Maiya Tokareva

The daughter of Nikolay Tokarev, Tokareva owns a what the Treasury Department calls a real estate empire valued at more than $50 million in Moscow, as well as at least three companies — one of which, based in Croatia, owns oceanfront property on a Croatian island that includes an villa built by Austrian Emperor Franz Joseph I.

Yevgeniy Prigozhin

This isn't the first time the U.S. has sanctioned Prigozhin. The financial backer of the Internet Research Agency, which runs massive social media influence campaigns , Prigozhin was previously sanctioned for facilitating attempts to interfere in U.S. elections. Prigozhin "directs the generation of content to denigrate the U.S. electoral process and funds Russian interference efforts while also attempting to evade sanctions by standing up front and shell companies both in and outside of Russia," according to the Treasury Department, which said Prigozhin's influence apparatus has been on sowing discord on social issues in Ukraine and attempting to spread disinformation about the United States government.

Prigozhin's networks also allegedly helped Russia interfere in elections and subvert public opinion in Asia; spread false narratives in Africa; and spread disinformation on European politicians in support of Russia's goals in Ukraine.

The U.S. also sanctioned his family members, including his wife Lyubov Prigozhina, and his daughter and son, Polina Prigozhina and Pavel Prigozhin.

Boris Rotenberg

First sanctioned by the U.S. in 2014, Rotenberg owns part of Russian oil and gas drilling company Gazprom Burenie, along with his nephew, Igor, according to the Treasury Department. At the time, Treasury said Rotenberg helped support "Putin's personal projects by receiving and executing high-price contracts for the Sochi Olympics and for state-controlled energy giant Gazprom."

After he was sanctioned, he and his brother Arkady Boris Rotenberg used shell companies to buy "tens of millions of dollars' worth of art from major auction houses" and others, despite the sanctions, according to the State Department .

The current round of sanctions, which also includes his wife Karina and his sons Roman and Boris, are for his role in SMP Bank.

According to Forbes , he is worth more than $1.1 billion and is also the vice president of the Russian Judo Federation.

Arkady Rotenberg

The brother of Boris Rotenberg, Arkady Rotenberg was also first sanctioned in 2014. According to the State Department , Rotenberg owns PSJC Mosotrest, which has helped build and maintain the Kerch Bridge between Russia and Crimea, which Russia has used to help claim sovereignty over the region it invaded in 2014.

cHe sold his son Igor his interest in the Russian oil and gas drilling company Gazprom Burenie, according to Treasury. The U.S. also sanctioned Igor, who was first sanctioned in 2018, and Rotenberg's other son Pavel and his daughter Liliya.

According to Forbes , he is worth $3 billion — and was once Putin's judo sparring partner. The International Judo Federation removed him from the Russian Judo Federation , where he was the "development manager."

Sergei Chemezov

When the U.S. originally sanctioned Sergei Chemezov in 2014, the State Department described him as "a trusted ally of Putin" whose long relationship dated back to the 1980s when they lived in the same East Germany apartment complex as the future Russian leader. Chemezov is now the CEO of the Russian state-owned conglomerate Rostec, which is involved in a number of industries, including defense.

Chemezov was sanctioned again last week along with his wife Yekaterina, his son Stanislav, and stepdaughter Anastasiya.

Igor Shuvalov

The U.S. also announced sanctions on Igor Shuvalov, who as chairman of VEB.RF, a state-owned development and investment firm, the State Department described as a member of Putin's inner circle. Like Usmanov, the U.S. also put a full block on Shuvalov's assets.

Shuvalov was a deputy prime minister under both Dmitry Medvedev and later under Putin. The Biden administration also specifically cited actions last week against Shuvalov's five companies, his wife Olga, his son Evgeny and his company and jet, and his daughter Maria and her company.

Like Usmanov, the U.K. also placed a full asset ban on Shuvalov, calling him "a core part of Putin's inner circle," and saying his assets in the U.K. include real estate worth more than 11 million pounds.

- Vladimir Putin

Allison Elyse Gualtieri is a senior news editor for CBSNews.com, working on a wide variety of subjects including crime, longer-form features and feel-good news. She previously worked for the Washington Examiner and U.S. News and World Report, among other outlets.

More from CBS News

Iran vows revenge for suspected Israeli airstrike on its consulate in Damascus

9 children dead after old land mine explodes in Afghanistan

Forbes has released its list of the world's billionaires

Botswana threatens to send 20,000 elephants to "roam free" in Germany

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Russian palaces, villas and yachts linked to Putin by email leak – in pictures, maps and video

Exclusive: A new investigation by the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project and the Meduza news site has found links through an email domain name that appear to connect opulent properties across Russia

- Full report

Vladimir Putin has been accused by western governments of amassing a vast secret fortune through a network of oligarchs and friends. However, there is little evidence on paper that links Putin to the assets – or the friendly benefactors to each other.

One possible connection has now emerged. An investigation by the the Organised Crime and Corruption Reporting Project and the news website Meduza has identified a group of 86 apparently unconnected companies or not for profit organisations that appear to hold over $4.5bn (£3.7bn) of assets where a common private email address, LLCInvest.ru, appears to be in use.

The assets which appear to be held by the organisations include a range of luxury homes, yachts and vineyards previously linked in media reports to Russia’s president. The telecoms company hosting the domain name on its servers is closely linked to Bank Rossiya, described by the US Treasury as “the personal bank for senior officials of the Russian Federation”.

None of the individuals or entities associated with the email domain name offered a comment or provided an explanation for the link when contacted. There is no suggestion that all the users of the LLCInvest.ru are involved in managing assets that have been linked in reports to Putin. It is unclear as to the purpose of the email service or the motivation for apparent cooperation on staffing and logistic issues. A Kremlin spokesperson said: “The president of the Russian Federation is not linked or affiliated in any way with the assets and organisations you mentioned.”

A £1bn palace which Alexei Navalny has claimed was built for Putin’s personal use in Gelendzhik on the Black Sea. The billionaire oligarch Arkady Rotenberg, who is under EU and US sanctions, has claimed ownership of the property. Corporate records held by the Spark database in Russia stated as of June that the property belongs to a firm called Kompleks whose parent company is Binom. The company director at Binom until July last year appears to have a registered LLCInvest.ru email domain. The LLCinvest.ru address remains cited on Spark, Russia’s largest company database, as a contact.

Acres of vineyards around the Gelendzhik palace. Navalny has claimed the wineries were a Putin “hobby” that had got out of control. Vineyards surrounding the palace belong to a not-for-profit founded by two Putin associates, Gennady Timchenko and Vladimir Kolbin, both of whom are also under western sanctions. Kolbin and others associated with the vineyards appear to have LLCInvest.ru email accounts.

The Igora ski resort in the Leningrad oblast where the wedding of Putin’s daughter took place in 2013. According to land records, it is owned by Ozon, a company in which Putin’s friend, Bank Rossiya’s chairman and largest shareholder Yuri Kovalchuk, who is under western sanctions, has a large stake. The LLCInvest.ru email account is a contact on the Spark records of Ozon’s parent company, Relax.

A dacha linked to Putin north of St Petersburg known as the Fisherman’s Hut, on the shores of Lake Ladoga near Valaam Island. Emails leaked from a construction company suggest that three different companies which appear to use the LLCInvest domain name own different parcels of land around the complex, while a fourth LLCInvest entity — a nonprofit organisation called the Revival of Maritime Traditions — managed the construction.

A villa north of St. Petersburg, known by locals as ‘Putin’s Dacha’. The Villa Sellgren, on the Gulf of Finland near Lodochny Island, is owned by Sergey Rudnov, the son of a childhood friend of the Russian president, through a company called North, according to corporate records. Rudnov appears to have a LLCinvest.ru email address in his name.

This 46-metre, $23m yacht with five decks and 10 bedrooms was built in 2015 by Sanlorenzo, an Italian luxury shipbuilder. According to the vessel tracking site MarineTraffic, the Shellest often travels between Gelendzhik, the resort town near Putin’s Black Sea palace, and the port of Sochi. It is owned by a non-profit organization called Revival of Maritime Traditions and has been identified by the US Treasury as being linked to Putin.

Additional credits: map by Pablo Gutiérrez and Seán Clarke. Video by Monika Cvorak. Picture research by Matt Fidler.

- Vladimir Putin

Most viewed

How a Playground for the Rich Could Undermine Sanctions on Oligarchs

Allies of President Vladimir Putin, arriving on private jets and yachts, are still welcome in the U.A.E., which has yet to condemn the Ukraine invasion or enforce sanctions.

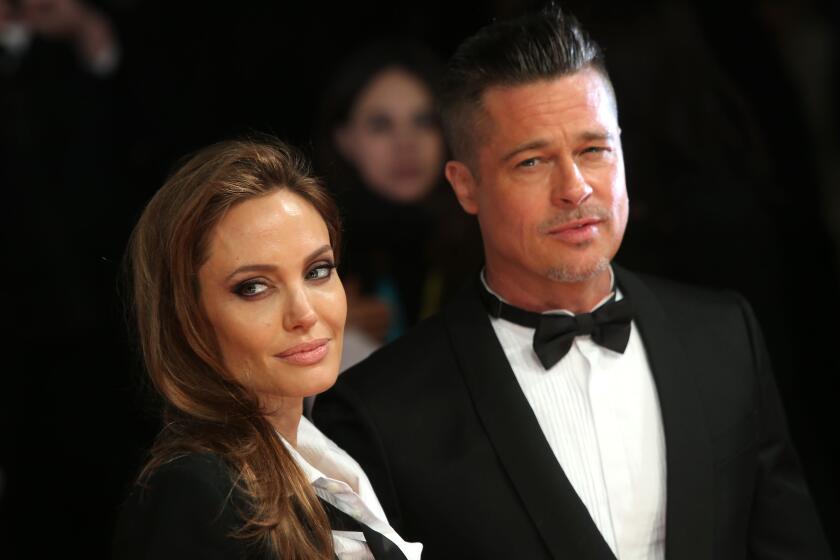

At least 38 businessmen or officials linked to Russia’s president own dozens of properties in Dubai collectively valued at more than $314 million. Credit... Christopher Pike/Bloomberg

Supported by

- Share full article

By David D. Kirkpatrick , Mona El-Naggar and Michael Forsythe

- March 9, 2022

Stretching into the Persian Gulf from the beaches and skyscrapers of Dubai is a man-made archipelago in the shape of a vast palm tree, its branchlike rows of islands lined with luxury hotels, apartments and villas.

Among the owners of those homes are two dozen close allies of President Vladimir V. Putin of Russia, including a former provincial governor and nuclear power plant manager, a construction magnate and former senator, and a Belarusian tobacco tycoon.

At least 38 businessmen or officials linked to Mr. Putin own dozens of properties in Dubai collectively valued at more than $314 million, according to previously unreported data compiled by the nonprofit Center for Advanced Defense Studies. Six of those owners are under sanctions by the United States or the European Union, and another oligarch facing sanctions has a yacht moored there. For now, they can count themselves lucky.

Since the invasion of Ukraine, much of the world has imposed sweeping sanctions on Russian financial institutions and the circle around Mr. Putin, and even notoriously secretive banking centers like Switzerland, Monaco and the Cayman Islands have begun to cooperate with the freezing of accounts, seizing of mansions and impounding of yachts.

But not Dubai, the cosmopolitan resort and financial center in the United Arab Emirates. Although a close partner to Washington in Middle Eastern security matters, the oil-rich monarchy has in recent years also become a popular playground for the Russian rich, in part because of its reputation for asking few questions about the sources of foreign money. Now the Emirates may undercut some of the penalties on Russia by continuing to welcome targeted oligarchs.

“Sanctions are only as strong as the weakest link,” said Adam M. Smith, a lawyer and former adviser to the U.S. Treasury Department office that administers such measures. “Any financial center that is willing to do business when others are not could provide a leak in the dike and undermine the overall measures.”

The Emirati stance is exposing tensions between the United States and several of its closest Arab allies over their reluctance to oppose the Russian invasion. Asked for solidarity in a moment of crisis, the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia and Egypt have instead prioritized relations with Moscow — the Emirates and Saudi Arabia by rebuffing American pleas for increased oil supplies to soothe energy markets, Egypt by muffling criticism of the invasion while proceeding with a $25 billion loan from Russia to finance a nuclear power plant.

“It should be a clarifying moment,” said Michael Hanna, U.S. program director for the nonprofit International Crisis Group. “That has to be pretty bracing.”

The U.A.E. may be the most conspicuous in its position, if only because it currently holds a rotating seat on the United Nations Security Council. The Emiratis abstained from an American-backed resolution denouncing the invasion, declining to criticize Russia. And Emirati officials have reassured Russians that their authorities will not enforce sanctions unless mandated by the United Nations — where Moscow’s veto ensures against it.

“If we are not violating any international laws, then nobody should blame Dubai, or the U.A.E., or any other country for trying to accommodate whoever comes in a legitimate way,” said Abdulkhaleq Abdulla, a political analyst close to the U.A.E.’s rulers. “So what’s the big deal? I don’t see why the West would complain.”

Russians in Dubai say they appreciate the hospitality. “Having a Russian passport or Russian money now is very toxic — no one wants to accept you, except places like Dubai,” said a Russian businessman who took refuge there, speaking on the condition of anonymity for fear of alienating Emirati authorities. “There’s no issue with being a Russian in Dubai.”

He shared an electronic invitation circulating among Russians in the city: a rooftop cocktail party for venture capitalists and cryptocurrency start-ups. (The Treasury Department on Monday warned banks to watch for Russians using cryptocurrency to evade sanctions.)

An Arab businessman who rents high-end furnished apartments in Dubai described “incredible demand” from Russians since the invasion, with one family taking an indefinite lease on a three-bedroom waterfront apartment for $15,000 a month and more than 50 other individuals or families seeking accommodations.

The Center for Advanced Defense Studies, a Washington-based nonprofit that collects data on global conflicts, found that Putin allies owned at least 76 properties in Dubai, either directly or under the name of a close relative, and said that there were likely many others who could not be identified.

The center’s list of those under sanctions includes: Aleksandr Borodai, a Duma member who acted as prime minister of a Ukrainian province in 2014 when it was taken over by Russian-backed separatists; Bekkhan Agaev, a Duma member whose family owns a petroleum company; and Aliaksey Aleksin, the Belarusian tobacco titan. A handful of oligarchs on the list own homes valued at more than $25 million each.

Maritime records show that in recent days the yacht belonging to the sanctioned oligarch Andrei Skoch, a steel magnate and Duma member, has been moored off Dubai.

A Bombardier business jet owned by Arkady Rotenberg, another Russian billionaire under sanctions, landed on Friday, and the planes and boats of other oligarchs discussed as possible targets have been coming and going, too. The yachts of at least three other oligarchs are currently docked in Dubai. The 220-foot vessel of a Russian metals magnate appears to be en route from the Seychelles. The Boeing 787 Dreamliner owned by Roman Abramovich, the Russian-born owner of Britain’s Chelsea soccer team, took off from the airport on Friday. A 460-foot superyacht belonging to another oligarch set sail the same day; he was added to Europe’s sanctions list on Wednesday.

Moscow has been quietly building closer ties to the U.A.E. and other Western-leaning Arab states for a decade, seeking to capitalize on complaints about Washington.

The autocrats who dominate the region were outraged by Washington’s statements of support for the Arab uprisings in 2011. The Arab monarchs of the Persian Gulf cried betrayal at the Obama administration’s deal with their adversary Iran over its nuclear program. Their frustration only grew when the Trump administration did nothing to retaliate for a series of apparent Iranian attacks against them.

Now people close to those rulers say that their neutral responses to the invasion of Ukraine should teach Washington not to take them for granted.

“The automatic expectation in D.C. is that ‘you Saudis now must jump on the bandwagon and isolate Russia as we have,’” said Ali Shihabi, a Saudi political analyst close to the royal court, but the kingdom cannot “burn” its relationship with Russia just to please the White House.

“Our relationship is there with the Americans,” he added, “but it is not going to be a monogamous relationship because the Americans are unreliable.”

Others noted that the Kremlin had overlooked human rights abuses that Washington often criticized, and that relations with an alternative power gave the Arab states more leverage. “It’s useful for Arab countries to take this stance,” said Mustapha Al-Sayyid, a political science professor at Cairo University.

Russia has sold weapons to all three countries, and a few Saudi military officers have begun training in Russia . Egypt and the U.A.E. have cooperated with Russia for several years in Libya, where all three have backed the same strongman in Eastern Libya in his conflict with the U.N.-backed government. Egypt provided bases near the border, the U.A.E. sent fighter planes and Russia deployed mercenaries.

Crown Prince Mohammed bin Zayed, the de facto ruler of the United Arab Emirates, visited Moscow at least six times between 2013 and 2018. When Mr. Putin visited the Emirati capital, Abu Dhabi, the next year, the city lit up landmarks in Russian colors and repainted its police cars with Russian banners and Cyrillic script.

Other entanglements bind their interests too, including the ongoing civil war in Yemen pitting partisans backed by Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates against others favored by Iran.

During a U.N. Security Council session last week, Russia unexpectedly supported an Emirati resolution to label the Iranian-backed fighters “terrorists.” Analysts sympathetic to the U.A.E. argued that it had won Moscow’s backing in part by abstaining from the resolution denouncing the Ukraine invasion.

Russia, though, has also used financial ties to pull the Gulf Arabs closer, partly through its state-controlled Russian Direct Investment Fund and its chief executive, Kirill Dmitriev, who last week was added to the sanctions list.

Created in 2011 to lure foreign capital to invest in Russia in partnership with its government, the fund initially courted Wall Street. Mr. Dmitriev, a Russian with degrees from Stanford University and the Harvard Business School, had once worked at a U.S. government-sponsored fund to invest in the former Soviet Union. For the Russian fund, he recruited an advisory board that included Stephen Schwarzman of the Blackstone Group and Leon Black of Apollo Global Management.

But the American financiers and money fled when Russia invaded Crimea in 2014. So Mr. Dmitriev turned east — securing investments worth more than $5 billion from the U.A.E. and more than $10 billion from Saudi Arabia. He also acted as an informal Russian envoy to the Gulf monarchs, talking foreign policy as well as money.

Mr. Dmitriev’s double role became especially clear after the 2016 U.S. presidential election. The Mueller report on Russian interference in the vote detailed how he had worked with Emirati leaders to try to connect on behalf of the Kremlin with those around Donald J. Trump — eventually preparing a short plan for “reconciliation” with Russia and getting it into the hands of Jared Kushner, the former president’s son-in-law and adviser, who shared it with top White House officials.

Rich Russians, though, have reasons other than geopolitics to buy property in Dubai. The sheikhs who ruled the city-state have long sought to attract business by allowing a high degree of secrecy about asset ownership and by sharing only limited information with other jurisdictions, said Maíra Martini, a researcher with Transparency International, which campaigns against corruption.

“Dubai has been a key player in most of the big corruption or money-laundering schemes in recent years,” she said, citing recent scandals involving Russian businessmen, the daughter of Angola’s former president, top Namibian fishing regulators and South Africa’s Gupta family.

Citing such failings, the Financial Action Task Force, an influential money-laundering watchdog, on Friday put the United Arab Emirates on its “gray” list.

A thriving colony of Russians in Dubai has made it a welcoming alternative to oligarch gathering spots like London’s Kensington neighborhood or the French Riviera. The Russian Business Council , a Dubai-based nonprofit, estimates that there are about 3,000 Russian-owned Emirati companies. The Russian embassy in the United Arab Emirates has said that about 100,000 Russian-speakers live in the country. About a million Russians visit each year. A Russian broadcaster, Tatiana Vishnevskaya , has built a career out of promoting life and commerce in Dubai. New real estate developments pop up “like mushrooms on a sunny day after the rain,” she recently told a tourism industry website.

A Russian company, the Bulldozer Group, owns a dozen upscale restaurants and nightclubs in Dubai, including the local Cipriani outpost. Caviar Kaspia, a French-Russian night spot, boasts of the “largest Vodka selection in Dubai.”

As in the current campaign against Russia, Dubai resisted earlier American-led sanctions against Iran, starting in 2006. Although the United Arab Emirates and Iran are opponents in regional politics, Dubai and Iran sit a short boat ride away across the Strait of Hormuz, and share trade and family ties going back centuries.

But after six years, pressure from Washington and the emirate of Abu Dhabi forced greater compliance on sanctions from Dubai’s big financial institutions, said Esfandyar Batmanghelidj, an economist at the European Council on Foreign Relations. Yet since 2019, when Abu Dhabi began reopening diplomatic contacts with Tehran, Emirati trade with Iran has quietly risen again, he said.

“They can calibrate it and turn it up and down,” Mr. Batmanghelidj added.

Emirati officials, seeking to get off the money-laundering “gray” list, are already pledging new transparency measures. Those steps could also limit the ability of sanctioned oligarchs to hide assets or move money in Dubai.

Cutting some Russian institutions off the international system for electronic bank transfers, called SWIFT, has already made it harder for them to do business with Dubai. And if Washington threatens to restrict Emirati access to the American financial system — as during the early years of the Iran sanctions — that could motivate the Emiratis to cooperate more.

Still, Washington often weighs its partnerships in military and intelligence matters against other priorities, including the enforcement of sanctions.

“The question,” said David H. Laufman, a lawyer who previously worked as a senior official in the national security division of the Justice Department, “is going to be how hard the Biden administration leans on the U.A.E. to get with the program.”

Sarah Hurtes contributed reporting.

David D. Kirkpatrick is an investigative reporter based in New York and the author of “Into the Hands of the Soldiers: Freedom and Chaos in Egypt and the Middle East.“ In 2020 he shared a Pulitzer Prize for reporting on covert Russian interference in other governments and as the Cairo bureau chief from 2011 to 2015 he led coverage of the Arab Spring uprisings. More about David D. Kirkpatrick

Mona El-Naggar is an international correspondent, based in Cairo. She writes and produces stories that cover politics, culture, religion, social issues and gender across the Middle East. More about Mona El-Naggar

Michael Forsythe is a reporter on the investigations team. He was previously a correspondent in Hong Kong, covering the intersection of money and politics in China. He has also worked at Bloomberg News and is a United States Navy veteran. More about Michael Forsythe

Our Coverage of the War in Ukraine

News and Analysis

President Volodymyr Zelensky of Ukraine has signed into law three measures aimed at replenishing the ranks of his country’s depleted army, including lowering the draft age to 25 .

With continued American aid to Ukraine stalled and against the looming prospect of a second Trump presidency, NATO officials are looking to take more control of directing military support from Ukraine’s allies — a role that the United States has played for the past two years.

Exploding drones hit an oil refinery and munitions factory far to the east of Moscow, in what Ukrainian media and military experts said was among the longest-range strikes with Ukrainian drones so far in the war .

Turning to Marketing: Ukraine’s troop-starved brigades have started their own recruitment campaigns to fill ranks depleted in the war with Russia.

Symbolism or Strategy?: Ukrainians say that defending places with little strategic value is worth the cost in casualties and weapons because the attacking Russians pay an even higher price. American officials aren’t so sure.

Elaborate Tales: As the war grinds on, the Kremlin has created increasingly complex fabrications online to discredit Zelensky and undermine Ukraine’s support in the West.

How We Verify Our Reporting

Our team of visual journalists analyzes satellite images, photographs , videos and radio transmissions to independently confirm troop movements and other details.

We monitor and authenticate reports on social media, corroborating these with eyewitness accounts and interviews. Read more about our reporting efforts .

Advertisement

Find anything you save across the site in your account

Putin’s Shadow Cabinet and the Bridge to Crimea

By Joshua Yaffa

In the spring of 2014, President Vladimir Putin delivered an address in St. George Hall, a chandeliered ballroom in the Kremlin, to celebrate the annexation of the Crimean Peninsula . “Crimea has always been an integral part of Russia in the hearts and minds of our people,” he declared, to a standing ovation. Despite Putin’s triumphal language, the annexation presented Russia with a formidable logistical challenge: Crimea’s physical isolation. Crimea, which is roughly the size of Massachusetts, is a landscape of sandy beaches and verdant mountains that juts into the Black Sea. It’s connected to Ukraine by a narrow isthmus to the north but is separated from Russia by a stretch of water called the Kerch Strait. Ukraine, to which Crimea had belonged, viewed Russia’s occupation as illegal, and had sealed off access to the peninsula, closing the single road to commercial traffic and shutting down the rail lines.

In response, Putin convened a council of engineers, construction experts, and government officials to look at options for connecting Crimea to the Russian mainland. They considered more than ninety possibilities, including an undersea tunnel, before deciding to build a bridge. The Russian state is notoriously inefficient at following through on the quotidian details of government administration; its more natural mode is building projects of tremendous scale. In keeping with this tradition of expanse, and expense, the bridge would span nearly twelve miles, making it the longest in the country, and would cost more than three billion dollars. When completed, it would symbolically cement Russia’s control over the territory and demonstrate the country’s reëmergence as a geopolitical power willing to challenge the post-Cold War order.

The bridge would be a demanding and technically complex project, however, and at first there were doubts about who would be willing to undertake it. Then, in January, 2015, the Russian government announced that Arkady Rotenberg, a sixty-three-year-old magnate with interests in construction, banking, transportation, and energy, would direct the project. In retrospect, the choice was obvious, almost inevitable. Rotenberg’s personal wealth is estimated at more than two and a half billion dollars, and the bulk of his income derives from state contracts, mostly to build thousands of miles of roads and natural-gas pipelines and other infrastructure projects. Last year, the Russian edition of Forbes dubbed Rotenberg “the king of state orders” for winning nine billion dollars’ worth of government contracts in 2015 alone, more than any other Russian businessman. But perhaps the most salient detail in Rotenberg’s biography dates from childhood: in 1963, at the age of twelve, he joined the same judo club as Putin. The two became sparring partners and friends, and have remained close ever since.

Rotenberg’s success is a prime example of a political and economic restructuring that has taken place during Putin’s seventeen years in office: the de-fanging of one oligarchic class and the creation of another. In the nineties, a coterie of business figures built corporate empires that had little loyalty to the state. Under Putin, they were co-opted, marginalized, or strong-armed into obedience. The 2003 arrest, and subsequent conviction, of Mikhail Khodorkovsky, the head of the Yukos oil company, brought home the point. At the same time, a new caste of oligarchs emerged, many with close personal ties to Putin. These oligarchs have been allowed to extract vast wealth from the state, often through lucrative government contracts, while understanding that their ultimate duty is to serve the President and shore up the system over which he rules.

The Crimean bridge is different from many of Rotenberg’s other state ventures, in that he is not expected to make much money from it. “This project is not about profits,” one banker in Moscow, who specializes in transportation and infrastructure, told me. He was matter-of-fact about how Rotenberg ended up in charge: “The bridge had to be built, and everyone else was refusing. It was the only possible solution.”

Construction began last year. Rotenberg, who has a reputation as an informed, hands-on manager, visits every few months, passing above the site in his helicopter before inspecting the project with a retinue of engineers and road-building specialists. Last fall, a correspondent from Russian state television filmed a fawning news segment about the bridge. Strolling with Rotenberg along one of the few completed sections, the host invoked the bridge’s reputation as “the construction project of the century.” The two put on hard hats and surveyed the jumble of cranes and excavators and drills in motion around them.

Rotenberg has the squat and powerful frame of a wrestler, and a round, impish face. His speech is clipped and straightforward, and he does not appear to enjoy introspection. But, when the television host pressed him to offer up platitudes on the bridge, Rotenberg did his best to oblige. “Besides financial profit—which, for a business, is a sign of success, of course—I also want the project to mean something for future generations,” he said. What Russians make of the bridge will be clear soon enough; the first cars will pass over it later this year. But its significance for Rotenberg already seems apparent. It is a totem of his service to the state and to its leader, Putin—and of their friendship, which has thrived at the intersection of state politics and big business.

Rotenberg was born in 1951 in Leningrad, a city deeply scarred by the Nazis’ two-and-a-half-year blockade during the Second World War. Rotenberg’s father, Roman, was a deputy director at the Red Dawn telephone factory, and his position gave the family a measure of stability and comfort. They lived in their own apartment, not a communal apartment like many families, including Putin’s. When Arkady was twelve, against his initial protests, his father took him to train with Anatoly Rakhlin, one of Leningrad’s better-known practitioners of sambo, a Soviet martial art that borrows from judo and was developed by Red Army officers in the nineteen-twenties. In a chaotic city, Rakhlin’s class offered teen-agers a redoubt of discipline. Putin, who was also in the class, said, in “ First Person ,” a book-length interview published during his first Presidential campaign, in 2000, that the training played a decisive role in his life. “Judo is not just a sport,” Putin said. “It’s a philosophy. It’s respect for your elders and for your opponent. It’s not for weaklings. . . . You come out onto the mat, you bow to one another, you follow ritual.”

Link copied

Rotenberg and Putin grew close travelling around Leningrad, and soon around the whole of the Soviet Union, for competitions. Nikolay Vaschilin, a retired K.G.B. officer who trained with them, remembers that the two were fond of pranks. (Putin later described himself during those years as “a troublemaker.”) One time, Vaschilin told me, the boys ran out of an alleyway during a May Day parade and threw wire pellets at balloons carried by the marchers, surprising them with a fusillade of pops. Another friend from that time recalled that he and Rotenberg would pilfer candy and other food from younger children at sports camps by sneaking up on them in the toilets, where kids would go to hide their treats from other boys: “They were immediately frightened and would give us a little something,” he said.

For fun, and a bit of spare cash, many of the young men in Rakhlin’s class worked as extras for a film studio in Leningrad, where they could earn ten rubles reënacting battle scenes in patriotic Soviet films about the Second World War. “Arkady showed himself to be a real brigadier,” Vaschilin recalled. “He was walking around and giving commands to everyone, even guys older than him. He was cocky, insolent, and mischievous—seventeen years old and already in charge.”

Putin had his eye on the K.G.B.—as he was later fond of recounting, he first volunteered his services when he was in ninth grade—but Rotenberg’s ambitions were in sports. He enrolled in the Lesgaft National State University of Physical Education, Sport, and Health, and graduated in 1978, after which he found work as a judo trainer. In 1990, Putin, after a K.G.B. posting in Dresden, took a job at the mayor’s office in Leningrad, which, a year later, after the Soviet collapse, was renamed St. Petersburg. Putin and Rotenberg, along with a handful of others from Rakhlin’s class, got together a few times a week to practice moves and stay in shape.

For Putin, who both by nature and by K.G.B. training is mistrustful of others, these early friendships seem to have been his only genuine, unguarded bonds. He would soon be surrounded by people who had something to offer, or something to ask. Rakhlin, who died in 2013, explained Putin’s affection for his former judo partners to the state-run newspaper Izvestia . “They are friends, and Putin’s character has maintained that healthy camaraderie,” Rakhlin said. “He doesn’t work with the St. Petersburg boys because they have pretty eyes, but because he trusts people who are proven.” In “First Person,” Putin said, “I have a lot of friends, but only a few people are really close to me. They have never gone away. They have never betrayed me, and I haven’t betrayed them, either. In my view, that’s what counts most.”

Trying to earn money in the nineteen-nineties, which were lean years in Russia, Rotenberg started a coöperative that organized sporting competitions with Vasily Shestakov, another boyhood friend from Rakhlin’s class. “We had worked in sports our whole lives,” Shestakov told me. “And then, all of a sudden, just like that: ‘perestroika,’ ‘business,’ all these unfamiliar words.” Neither had a talent for running a company. “Each of us thought the other one would do something,” Shestakov said. “And, as a result, no one did anything, and our coöperative fell apart.” Later that decade, Arkady’s younger brother, Boris, moved with his wife, Irina, to Finland. Before long, thanks to connections of Irina’s in the Russian gas industry, the brothers were trading in petroleum products. Irina and Boris separated in 2001, but she remains fond of the Rotenberg family. (She now goes by the name Irène Lamber.) “They have a natural intellect, a reasonable relation to everything, with a deep study of questions,” she told me. “All this was instilled in childhood.” Lamber suggested that business was not a true calling for them but an accident of fate. “Where would they be if the Soviet Union had never collapsed?” Lamber asked. “Arkady would be in charge of a state sports organization. He is a natural manager. And Boris would be a successful trainer.”

In the mid-nineties, Shestakov and a few others approached Putin, who was then the vice-mayor of St. Petersburg, with the idea of creating a professional judo club in the city. Putin gave his approval, and a number of wealthy businessmen—including the oil trader Gennady Timchenko, who knew Putin from city government—provided the funds. Rotenberg was named general director of the club, which was called Yavara-Neva. In the club’s second year, it came in second at the European Cup; the next year, in the German city of Abensberg, it won outright. On the judo mat, Rotenberg seized the championship trophy and gave it a kiss. “It left a good impression,” Shestakov told me. “I think that, of course, Putin was pleased.”

Since then, Yavara-Neva has won nine Euro Cups and produced four Olympic champions. Rotenberg remains the club’s general director. It is now building a new campus, which, in addition to a thousand-seat arena, will include a housing complex and a yacht club. Its cost is estimated at a hundred and eighty million dollars, paid for, in part, out of the St. Petersburg and federal budgets. When I met Alexey Zbruyev, the club’s athletic director, I asked whether Yavara-Neva might enjoy preferential treatment because of its connection to the President—for example, in financial donations from businessmen or in zoning approvals from bureaucrats. “We don’t brag about it anywhere,” Zbruyev said. “Everyone knows this perfectly well—why bring it up yet again? They know what Yavara-Neva is and who the club’s leaders are. Beyond that, no one asks any questions.”

In 2000, President Boris Yeltsin named Putin his successor, setting in motion a reorganization of the country’s political life. Putin believed that Russia had grown weak and ineffectual in the nineties, and during the first year of his Presidency he and a council of economic advisers carried out reforms meant to bolster the authority and the competency of the state. Some of those early reforms, such as the introduction of a flat tax, hewed to a pro-market, neoliberal framework. But one day Andrei Illarionov, a liberal-minded economist who was working closely with Putin, came across a Presidential order to create a state monopoly by combining more than a hundred liquor factories. No one had mentioned this new body, Rosspirtprom, at council meetings. Illarionov asked other Putin advisers if they knew about the plan, and none did.

“We had been discussing every issue related to the economy, so to come across a decree no one had heard of was quite a shock,” Illarionov told me. At best, Rosspirtprom would create another clunky bureaucracy at a time when Putin had promised to pursue the opposite course; at worst, Illarionov feared, it would be an opaque company that would allow for favoritism and corruption. “It was clear that there were other people, besides our economic council, from whom Putin was taking advice, and that he was making decisions for their benefit.”

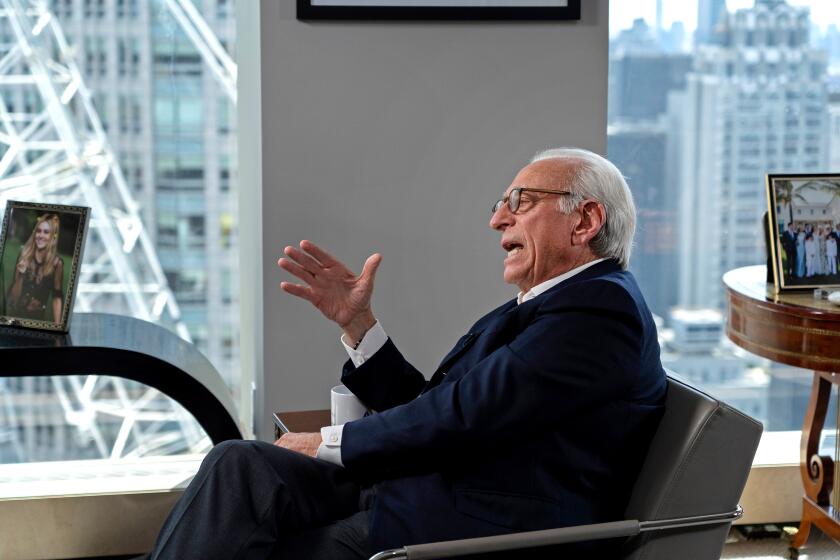

Rotenberg and Putin were judo sparring partners

In the case of Rosspirtprom, that person was Rotenberg. He had suggested that Sergey Zivenko, with whom he had done business in the nineties, be put in charge of the company. When I met Zivenko, last fall, he called the creation of Rosspirtprom “a joint initiative” with Rotenberg—“a business project with a political tinge.” Rosspirtprom eventually controlled thirty per cent of the country’s vodka market, making it a key source of income for the state in the years before global oil prices skyrocketed. The company was an early test of Putin’s model of state capitalism, and, because it returned financial resources, and thus political power, to the Kremlin, Putin considered it a success.

Rotenberg also profited from the centralization, likely with Putin’s blessing. According to the logic of the Putin era, corruption is stealing without actually doing anything. Personal enrichment is seen as the proper reward for a completed project. “A lot of people tried to use their closeness with Putin to make a lot of promises they never carried out,” Zivenko said. “But not Rotenberg. He used this trust and delivered tangible accomplishments.” Rotenberg began using the success of Rosspirtprom “like his business card,” Zivenko said. Russian officials, and other businessmen, “saw that he was able to lobby his interests with the President, and must really be close to him, and so we have to be friends with him, too. Arkady was able to capitalize on—monetize, really—this image.”

In 2001, just before oil prices began a historic surge, Putin replaced the top executives of Gazprom, the major Russian gas company, with close associates, effectively bringing the company under the Kremlin’s direct control. Mikhail Krutikhin, a partner at RusEnergy, a consultancy in Moscow, told me that Gazprom began functioning as “the personal company of the President—all decisions regarding Gazprom, whether launching big investment projects or naming top corporate officials, were made by the President’s office.” Around this time, Arkady and his brother, Boris, began investing in companies that serviced Gazprom. They founded SMP Bank in 2001, and used it to acquire stakes in construction, gas, and pipe companies; by the mid-aughts, the brothers had become one of Russia’s main suppliers of large-diameter gas pipes.

At nearly every turn, Gazprom spent more than seemed necessary or appropriate—and, in many cases, the Rotenberg brothers stood to benefit. To take just one example, in 2007, when Gazprom needed to deliver gas from a new field above the Arctic Circle, it decided against a plan, which had been circulating for years, that called for building a short link to an existing network three hundred and fifty miles away. Instead, it built a brand-new pipeline fifteen hundred miles to the south, with a final price tag of forty-four billion dollars—three times what a pipeline of that length usually costs. “The only explanation was that this was a chance for contractors to make a lot of money,” Krutikhin said.

When Gazprom built pipelines inside Russia during the next decade, they were two to three times more expensive than equivalent projects in Europe, even when they were in temperate, accessible areas in southern Russia. Perhaps the most striking example of inefficiency occurred in 2013, when Gazprom announced that the cost of a pipeline that Rotenberg was building in Krasnodar—a warm, flat region near the Black Sea—had risen by forty-five per cent. No explanation was given; wages were relatively stable, as was the price of steel. That stretch of pipeline was meant to feed into a larger pipeline going through Bulgaria. After the Russian government suspended construction on the Bulgarian pipeline, Rotenberg’s project miraculously went on for another year. Mikhail Korchemkin, the head of East European Gas Analysis, said that it became clear that Gazprom had “switched from a principle of maximizing shareholder profits to one of maximizing contractor profits.” The company’s projects, he said, presented a “way of minting new billionaires in Russia: overpay for services and make them rich.”

Rotenberg’s greatest business achievement came in 2008, when Gazprom sold him five construction and maintenance companies, for which he paid three hundred and forty-eight million dollars. He merged the firms into a single company, Stroigazmontazh (or S.G.M.), which immediately became one of the chief contractors for Gazprom. In the company’s first year of operations, it earned more than two billion dollars in revenue, an amount that suggested that the sale price was many times lower than market value. A short time later, the Rotenberg brothers bought a brokerage firm called Northern European Pipe Project. The normal profit margin for such companies is around ten to fifteen per cent, but several people with knowledge of the industry said that, during the boom years, N.E.P.P. earned as much as thirty per cent. At the height of its operations, it supplied ninety per cent of all large-diameter pipes purchased by Gazprom.

Before the Crimean bridge, no construction project was as personally important to Putin as the preparations for the 2014 Winter Olympics , in Sochi. The city of Sochi, which is on the far-western edge of Russia, overlooking the Black Sea, was developed as a resort area under the tsars, and later became a favorite retreat of Soviet workers, but it had little in terms of modern athletic infrastructure. Nearly everything, from ski resorts to the mountain roads leading up to them, had to be built from scratch, and before long the 2014 Games had become the most expensive in history, with an estimated budget of fifty-one billion dollars. One company controlled by Rotenberg built a nearly two-billion-dollar highway along the coast. Another built an underwater gas pipeline leading to Sochi at a price well over three times the European average. In all, companies controlled by Rotenberg received contracts worth seven billion dollars —equivalent to the entire cost of the previous Winter Olympics, in Vancouver, in 2010.

It is impossible to identify the line between where the Rotenberg brothers have, thanks to their name and connections, pocketed outsized profits from state contracts and where they’ve merely had a knack for finding opportunities to make money. When I asked Irène Lamber, Boris’s ex-wife, whether Putin actively assisted the Rotenberg brothers, she told me that she wouldn’t rule it out. “They were friendly in childhood, and those relationships were never broken, so logically you can presume some sort of advice was given, at a minimum, and perhaps help here and there,” she said. As Konstantin Simonov, the director of the National Energy Fund, put it to me, “The story is simple: with a company like Gazprom, not just anybody can show up off the street and say, ‘I want to build a giant gas pipe.’ It’s clear that Rotenberg needed a serious degree of political support on the first step.” But personal favors alone didn’t make Rotenberg successful. “Rotenberg proved himself to be a very tenacious guy, with real organizational skills and a willingness to take risks,” Simonov said.

When I spoke with Bogdan Budzulyak, a former Gazprom board member, he was full of praise for the Rotenbergs, and told me that the ties between the brothers and Putin “were not raised or spoken about. But we understood, it goes without saying, that they had earned the trust they were given.” Rotenberg has directly addressed the friendship in a few interviews. “I would never go to the President and ask him for something,” he told one reporter. “That would mean depriving myself of the pleasure I get from our conversations.” In the Russian edition of Forbes , he acknowledged that “knowing someone at that level has never hurt anyone,” but argued that the bond only makes things harder for him. “Unlike a lot of other people, I don’t have the right to make a mistake,” he said. “Because it’s not a question of just my reputation.”

In the nineties, Russia’s oligarchs appropriated state assets—industrial production, mining, and oil and gas deposits—and did what they wanted with them. The oligarchs of the Putin era, on the other hand, are themselves assets of the state, administering business fiefdoms that also happen to pay handsomely. Many have a long-standing relationship with the President, and a particular sphere of responsibility. Rotenberg’s is infrastructure. Gennady Timchenko, one of the initial supporters of Yavara-Neva, came to preside over the oil trade; at one point, a firm he controlled sold as much as thirty per cent of the country’s oil exports. Yury Kovalchuk is the Kremlin’s unofficial cashier and media minister; the U.S. Treasury Department called him “the personal banker for senior officials of the Russian Federation, including Putin.” Bank Rossiya, which he chairs, is worth ten billion dollars, and Kovalchuk’s personal wealth is estimated at one billion dollars.

“If oligarchy 1.0 tried to grab pieces of the economy from the state, and use them for themselves, then oligarchy 2.0 tries to build themselves into the state system, in order to gain access to state contracts and budget money,” Ekaterina Schulmann, a political scientist and noted analyst of the Russian political system, explained. As Clifford Gaddy, an economist who studies Putin’s economic strategy, put it, “His vision of the country’s entire economy is ‘Russia, Inc.,’ where he personally works as the executive director” and the owners of nominally private firms are “mere divisional managers, operational managers of the big, real corporation.”

A source close to the Kremlin insisted that the rise of Rotenberg and similar Putin-era nouveau oligarchs was not the result of a purposeful plan: “It wasn’t Putin’s strategy to create these people. That’s a fantasy. He may have agreed to help them, and at a certain point, once they became large and successful, he realized that they might be useful, that it’s not so bad to have a caste of very wealthy people who are obligated to you.” In effect, Putin’s oligarchs form a shadow cabinet. Evgeny Minchenko, a political scientist in Moscow, told me, “These are trusted people, who will stick with Putin until the end, to whom he can assign certain tasks, who won’t get frightened by external pressure.” They can take on projects the Kremlin doesn’t want to fund or manage, such as sports teams, media programs, and political initiatives.

A well-connected banker told me that many oligarchs finance the “black ledger,” which, as the banker explained, is “money that does not go through the budget but is needed by the state, to finance elections and support local political figures, for example.” Funds leave the state budget as procurement orders, and come back as off-the-books cash, to be spent however the Kremlin sees fit. The Panama Papers, leaked last April, revealed that, between 2007 and 2013, nearly two billion dollars had been funnelled through offshore accounts linked to Putin associates. In 2013, companies affiliated with Rotenberg sent two hundred and thirty-one million dollars in loans, with no repayment schedule, to a company based in the British Virgin Islands. What happened to that money is a mystery. A spokesperson for Rotenberg said it was transferred for “specific transactions under commercial terms,” without clarifying the nature of the deal. Separately, tens of millions of dollars passed through offshore companies registered to Sergey Roldugin, a cellist who befriended Putin in the seventies and who is the godfather of Putin’s eldest daughter, Maria. Addressing the transactions last April, Putin said of Roldugin: “He spent almost all the money he earned acquiring musical instruments from abroad and bringing them to Russia.” (Roldugin has denied any wrongdoing.) Putin’s thinking seems to be that there is no need to own anything himself, at least on paper, when trusted allies can do it for him.

Putin’s Russia has been given many labels, from kleptocracy to Mafia state, but the most analytically helpful may be among the oldest: feudalism. “It is not a metaphor but a very exact definition of the system,” Andrey Movchan, a banker and finance expert in Moscow, said. If in the Middle Ages the chief feudal currency was land, in today’s Russia it is hydrocarbon wealth. Movchan explained how, in the Middle Ages, feudal lords were often “one handshake away from the king: their post, and the size of the resource, was decided by the king alone.” The land ultimately belonged to the king, and was awarded to feudal lords on a provisional basis. The same is true in Russia today, he said.

The system that Putin has established suggests a degree of weakness, insecurity, and even fear. Putin has little faith in the effectiveness of his rule, which is why true responsibility in his state is shared by only a handful of intimately connected people. Schulmann told me that in Russia’s political system “there are no such things as qualifications, talent, skill, experience. None of that is important.” What is important, she said, parroting Putin, “is that I’m not afraid. And the only way I won’t be afraid is if I see a familiar face next to me.” She continued, “How can I protect myself? I grab my friend Arkady, one of the few people I can trust.”

In November, 2013, a wave of protests swept through the Ukrainian capital, Kiev. Initially sparked by President Viktor Yanukovych’s refusal to sign a trade deal with the European Union, they quickly grew to include objections to the corruption of Yanukovych’s administration and its violent response to the demonstrations. The movement reached a chaotic end in February, 2014, when Yanukovych fled the capital in the middle of the night. Putin, fearing that Ukraine was turning toward Europe, secretly ordered Russian forces to enter the Crimean Peninsula. Crimea had been a part of the Russian Empire from the eighteenth century until 1954, when Nikita Khrushchev gave it to Soviet Ukraine as a gesture of friendship. Much of the Crimean population still had great affection for and close cultural ties to Russia, which many locals call their “big brother.” It wasn’t difficult for Putin to whip up a pro-Moscow campaign, fuelled by propaganda and backed by Russian special forces. In a stage-managed referendum, ninety-seven per cent of Crimeans voted to join Russia. Russian-backed separatists were soon battling the Ukrainian military in Eastern Ukraine; at several key points, Russian forces intervened to shift the momentum in the fighting.

In March, 2014, the Obama Administration imposed sanctions on Russia for its interference in Ukraine; it included Arkady and Boris Rotenberg on its list of sanctioned individuals. The Treasury Department identified the brothers as “members of the Russian leadership’s inner circle,” who “provided support to Putin’s pet projects by receiving and executing high-price contracts for the Sochi Olympic Games and state-controlled Gazprom.” (Arkady, but not Boris, was added to the E.U.’s sanctions list that July.) It is unclear what role, if any, Arkady played in the Kremlin’s Ukraine policy, but that wasn’t the point. “We wanted to make clear to the inner circle that Putin can’t protect them, that he can’t shield his cronies,” Daniel Fried, who was in charge of the sanctions policy in the State Department during the Obama Administration, told me. The theory was that sanctions would make the lives of rich and powerful individuals close to Putin more difficult, and certainly less profitable, and that their material suffering might deter further aggression.

Rotenberg did experience some inconveniences. Visa and MasterCard stopped servicing cards issued by SMP Bank, but the bank is as much a hub for Rotenberg’s personal businesses as it is a commercial project. In September, 2014, Italian authorities seized a number of Rotenberg’s properties in Italy: among them, three villas on the island of Sardinia, one in the city of Tarquinia, and a luxury hotel in Rome. The newspaper Corriere della Sera estimated the combined value of the real estate at thirty million euros. Rotenberg admitted that the sanctions have forced some adjustments in his life: “Before, I used to wonder whether I should go to France or Italy—I loved to vacation in Italy—but now there is no such question. There are plenty of beautiful places in Russia.” After Rotenberg’s properties in Italy were taken, Russia’s parliament considered what came to be known as “the Rotenberg law,” which proposed that the state compensate Russian citizens for assets seized by foreign governments. (The bill was never passed; Rotenberg said that he had nothing to do with it.)

Contrary to the Obama Administration’s hopes, however, Rotenberg drew even closer to Putin. So did Timchenko and Kovalchuk, who were also on the sanctions list. Their response was partly about personal loyalty. “I have great respect for Putin and I consider him sent to our country from God,” Rotenberg told the Financial Times . But it also made rational sense: the Russian state is Rotenberg’s main client and source of wealth, so it would be far costlier to turn against Putin than to bear the burden of sanctions.

In fact, Western sanctions may have been a boon for Rotenberg, giving him a chance to show Putin that he had suffered for the country and was owed some payback. “It’s now quite obvious that whoever ended up under sanctions found himself in a more privileged position,” Minchenko, the political scientist, said. In a roundabout way, he told me, the United States and the E.U. “made a contribution to the increased influence of these people.” Indeed, after the sanctions, Rotenberg’s state orders grew: in 2015, he received nine billion dollars in government contracts, compared with three and a half billion dollars the year before.

In November, 2015, Russia began charging long-distance truck drivers a per-kilometre toll for travelling on federal roads. One of the co-owners of the company awarded the contract for the toll system was Igor Rotenberg, Arkady’s forty-two-year-old son, who has taken over major shares in several businesses once held by his father. Documents later showed that Igor’s company, which had no competition for the contract, would be paid a hundred and fifty million dollars each year until 2027, according to the exchange rate at the time. In a rare flash of unrest, hundreds of truck drivers protested the measure, blocking highways leading into Moscow and posting signs in their windshields that read “Russia Without Rotenberg” and “Rotenberg Is Worse Than ISIS .” When, this spring, the toll was further increased, demonstrations erupted again, especially in the North Caucasus, where drivers formed protest encampments.

Any enterprise to which Rotenberg lends his name now seems to succeed. In 2014, as the Times reported , after Rotenberg became the chairman of a Russian textbook publisher, Enlightenment, the Ministry of Education and Science eliminated more than half the titles in the country’s schools, often for flimsy technical reasons. Enlightenment, whose books were largely untouched, was left with an outsized share of a market worth hundreds of millions of dollars a year. This past winter, the Moscow city government decorated the center of town for the New Year; as an investigation by the independent Russian news site Meduza found, a company affiliated with the Rotenberg brothers was awarded a contract to install the decorations. According to Meduza, the company charged the city nearly five times the actual cost for dozens of illuminated garlands in the shape of champagne flutes: about thirty-seven thousand dollars instead of eight thousand dollars for each light fixture. (A spokesperson for Rotenberg denied any affiliation with the firm.)

Ilya Shumanov, the deputy director of the Moscow office of Transparency International, said that, although many of these deals seem suspect, it would be difficult to catch Rotenberg “red-handed breaking the law,” not only because of his robust legal staff, but because the various arms of the Russian state, from parliament to government auditors, work together to create a “legal window” for his business. For example, although Russian law requires that state procurement contracts be awarded through open bidding, it also allows them to be granted in a closed, no-bid process if the projects are deemed strategically important—a category that the state itself determines, and doesn’t have to explain or justify. A 2015 report prepared for the Russian government showed that ninety-five per cent of state purchases were uncompetitive, and forty per cent were made with a single supplier. Many of Rotenberg’s largest and most lucrative orders have been awarded without open bidding. One gas-industry expert told me that in some cases fake companies were even set up to pose as bidders. As Shumanov put it, “You could call it an imitation of legality. The letter of the law is observed, even if it is broken in spirit.”

The idea of building a bridge to Crimea was first raised by a British imperial consortium in the late nineteenth century, when engineers briefly considered a rail line that would run from London to New Delhi, via the peninsula. In the nineteen-thirties, under Stalin, Soviet railway planners revived the proposal as part of the country’s industrialization drive, but the project went nowhere. During the Nazi campaign to seize the Caucasus, in 1942, German soldiers took the first steps to construct a bridge. Before they could complete the project, Soviet soldiers captured the area. Within a few months, Red Army engineers had built a one-track rail bridge, but in February, 1945, four months after the first freight train passed over it, an ice floe hit the bridge and it collapsed.

Soviet officials returned to the idea of a bridge from time to time in the following decades, but the proposals were always rejected as too expensive. The Kerch Strait is a challenging place to build, with complicated geology, high seismic activity, and stormy weather. The seafloor is covered in a layer of crumbly silt that reaches as deep as two hundred feet. Freshwater from the Don River flows into the sea, which means that the surface often freezes in winter; high winds create cracks in the ice, and as the ice floes break apart they put pressure on anything standing in the water.

Oleg Skvortsov, an engineer with a long career overseeing bridge construction, was the chairman of the council of experts that advised the Russian government on the Crimea project. He said that, in the nineties, when it was a kind of fantasy, he opposed the idea of a bridge. “But the situation changed,” he said, with Ukraine’s blockade. Crimea has to find a way to transport its fish, wine, fruit, and other goods to Russia. “I love Crimean peaches, for example,” he said. “You can only find such peaches in Italy.” Skvortsov told me that he “wouldn’t consider Rotenberg a builder,” and then began to talk about his father, an engineer who worked under Feliks Dzerzhinsky, the chief commissar for railway construction in the twenties—and also a notorious and feared Bolshevik and the founding head of the Soviet secret police, which later became the K.G.B. “He rebuilt all the rail lines in a ruined country,” Skvortsov said of Dzerzhinsky. “My father said he was a brilliant supervisor, largely because he never got too involved in technical details. I think Rotenberg is the same way.”

Like most economic activity connected to Crimea, the bridge is a target of U.S. sanctions. Fried, the former State Department official, told me, “We never thought we could prevent the bridge, but we could try and make it massively costly and radioactive, so that Crimea never pays for itself, that it turns out not to be a war prize but a liability.” The sanctions do not seem to have affected construction or greatly raised costs, but they have created a few complications. It initially proved impossible to find an established insurance company to underwrite the project, and so an obscure insurance company in Crimea took on more than three billion dollars in potential risk.

As Russia began to slide into recession, the bridge started to look more and more like an extravagance. In the past several years, the Kremlin has cut budget expenditures in nearly every category. In February, an official with Russia’s roadways agency let slip, perhaps accidentally, how many resources the bridge was using. “On account of this bridge, the building of new automobile roads in Russia has been practically suspended,” he said. “The country does not have enough money. Therefore, we cannot implement everything we want.”

Still, if the Kremlin considers a project a priority, it can successfully mobilize the country’s resources. Mikhail Blinkin, the director of the transportation institute at the Higher School of Economics, in Moscow, told me that big infrastructure projects in Russia are often held up by piecemeal financing and bureaucratic roadblocks. “But in the Kerch case,” Blinkin said, “the funding was sufficient, and all the usual obstacles were eliminated on the political level.” It now appears likely that the bridge will be fully operational, to train and car traffic, a year ahead of schedule—in time for the next Presidential election, Putin’s fourth. In an attempt to boost turnout by appealing to patriotic sentiment, the vote may be held on the anniversary of Crimea’s annexation.

Blinkin told me that the bridge wasn’t strictly necessary; Crimea could accommodate travellers to and from the peninsula by simply increasing the number of ferries between the city of Kerch and the Russian mainland. He noted that far more passengers travel between Helsinki and Stockholm, for example, exclusively by ferry. But an expansion in ferry service is not as grand as a bridge, and doesn’t send a message about Russia’s status as a world power. “Is that worth such gigantic expense?” Blinkin asked. “In a strict economic sense, no. But, if you factor in the political component, then yes.”

I visited the bridge in January. It is being built not in a line, from one end to the other, but in eight separate parts at once, and for the moment it resembles a concrete-and-steel archipelago rising from the sea. On the mainland side, construction is centered in the town of Taman, which was settled by Cossacks in the eighteenth century, and which Mikhail Lermontov, in his novel “ A Hero of Our Time ,” called “the nastiest little hole of all the seaports of Russia.” When I arrived in Taman, the streets, quiet save for a few construction workers, were covered in a dusting of snow, and a freezing wind snapped through town.

At the bridge site, teams of workers watched over drills the size of redwood trees, which rammed steel piles into the seafloor. The scale of construction was almost too immense to comprehend. As the foundation of the bridge curved toward Crimea, it disappeared on the horizon. In a trailer, I sat down with Leonid Ryzhenkin, an official from Rotenberg’s construction company who is in charge of the site and its five thousand workers. Ryzhenkin’s wife’s family is from Sevastopol, a storied naval port in Crimea, and in the tense days before the referendum, one of his in-laws joined a pro-Russian militia. He told me about spending five hours taking a ferry and then a taxi to visit his in-laws. “My elderly mother-in-law calls all the time and asks, ‘So, Lenya, how’s it going? When are we going to drive across the bridge?’ ” he said. “And I tell her not to worry, we’ll make it in time.” He told me that Crimea is home to “native Russian people,” and that the bridge will “allow us all to be reunited.”

Roman Novikov, an official from Russia’s state road agency, joined us, and when I asked his assessment of Rotenberg he was eager to respond with praise. “I have the sense that he is deeply immersed in the project,” Novikov said. He offered an explanation for Rotenberg’s interest. “It’s no secret that he talks with his childhood friend, from when they were young, who is also interested, of course, in this object,” he said. Just in case there was any confusion, Novikov clarified: “I am speaking of the President of the Russian Federation.” ♦

By signing up, you agree to our User Agreement and Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement . This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

By Mark Lawrence Schrad

By Ed Caesar

By Benjamin Kunkel

Financial Transparency Coalition

The Rotenberg Files: a guide on how Russian kleptocrats dodge sanctions

June 22nd, 2023

The sanctions against Russian oligarchs who hold billions of dollars have mostly failed to have a real impact beyond freezing a few yachts and properties. So, what went wrong? Now we know.

The “ Rotenberg Files ”, a mass leak of over 42,000 emails and documents, has showed how Russian oligarchs Boris and Arkady Rotenberg hid their assets and those of Vladimir Putin, using trusts and private equity investment funds, taking advantage of the lack of public beneficial ownership registries.

Since the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2014 and especially since 2022, sanctions on Russian oligarchs and legal entities linked to the Russian invasion of Ukraine include 12,900 designations against Russia . Some estimates say that Russian oligarch offshore wealth is over US$1 trillion , but sanctions so far have only frozen US$58 billion , due to difficulty in establishing ownership.

Sanctions vary but have been mainly implemented by G7 countries and the European Union. Their effectiveness depends on setting up beneficial ownership registries that cover all possible legal vehicles, and the obligation to cross-check beneficial owners against sanctions regimes by a wide variety of professional enablers for due diligence purposes.

This has largely not happened. Despite progress in establishing centralised beneficial ownership registries, a commitment made by nearly 100 countries , very few of them are open to public access and are ridden with loopholes. In reality, global South countries are now leading the way in establishing effective BO registries after the European Court of Justice ended public access to EU-wide BO registries in November 2022 .

To take an example, in the British Virgin Islands (BVI) the Beneficial Ownership Secure Search System Act (the BOSS Act ) creates an obligation to report beneficial owners to the authorities since 2022, with the view of this being an open registry at some point in the future.

It came as a surprise to the Rotenbergs that this regime was being implemented. Leaks confirm that “BVI authorities were asking for the identities of the beneficial owners of at least 18 companies that belonged to the Rotenbergs or their intermediaries.” The leaked message added that: “Apparently the BVI Financial Services Authority obliges the BVI agents to resign from companies whose [ultimate beneficial owner] is listed in the…(US sanctions).”

However, this did not freeze or stop their assets from being utilised. The simple work around was to name a proxy or a nominee. The enablers of this financial secrecy proposed that leaks show that “[w]e can name some trusted person as a nominal [beneficial owner] and issue a trust declaration in favour of Rotenberg.”

Indeed trusts have become the legal vehicle of choice by Russian oligarchs to hide their wealth. They are also very hard to detect as the presence of a trust deed can be kept at a lawyer’s office if there is no requirement to register the trust in a beneficial ownership registry. Many BO registries do require declaring trusts , but there are loopholes that allow for setting up trusts in jurisdictions that do not require registration of trusts or have loopholes regarding thresholds or exemptions. Only 65 countries require some form of registration of trusts .

Eight of the 18 BVI companies mentioned in the Rotenberg leaks were ultimately dissolved, and two relocated to Cyprus. This implies that Cyprus has become a key location to use trusts and other instruments to conceal ownership. As a European Union member, Cyprus was obliged to create a central register of beneficial ownership in line with the EU’s fifth Anti-Money Laundering Directive. Trusts based in Cyprus do come under this requirement, but the Rotenbergs used a loophole in the BO laws to conceal ultimate ownership that goes around the existing EU 5 th Anti-Money Laundering Directive .

They effectively created a complex ownership structure around different entities in order to be below the trigger points for reporting beneficial ownership (in most cases 25 percent of control), yet still retaining control through power through potential voting coalitions in the complex structure that were concealed elsewhere. The structure used by the Rotenbergs involved a US entity that is owned by entities elsewhere , including Italy, the UK, Luxembourg, Cyprus, Bahamas (four entities), the British Virgin Islands and Cayman Islands,

Along with trusts, private equity firms have been revealed as another preferred vehicle to dodge sanctions. Investment vehicles called “closed mutual funds,” in Russian abbreviated as “ZPIFs,” held these assets. They are not considered legal entities under Russian law, and thus are not under obligations to reveal their shareholders to the authorities. The leaked files show that 13 ZPIFs were linked to the Rotenbergs.

To evade questions about the true nature of the beneficial owners, the leaked files show that “there is a practice where the General Director of the Management Company is recognized as the ultimate beneficiary”. The ZPIF’s invested in Russian companies, Monaco real estate, and other assets where beneficial ownership checks do not take place. Companies where they owned minority stakes could do business relatively normally.

Private equity and mutual funds are a global concern. According to a recent report, “Private Investments, Public Harm” , there are nearly 13,000 investment advisers in an $11 trillion industry with little or no anti-money laundering due diligence responsibilities in the USA, with the real possibility that sanctioned oligarchs use such vehicles to conceal their ownership. The US Enablers Act seeks to remove the exemption from due diligence checks from investment managers but the bill did not pass last December.

Art is another way to conceal ownership, as art dealers are not under any reporting requirements for money laundering purposes. A July 2020 report by a U.S. Senate subcommittee detailed an elaborate scheme in which the Rotenberg brothers spent more than US$18 million on art purchases in the months after they were sanctioned by the U.S. in March 2014. They acquired several artworks , including a US$7.5 million René Magritte, through a web of offshore companies based in Cyprus and the British Virgin Islands.